Deep Benedict

Hey readers, I will be traveling today, to the Symposium on Advancing the New Evangelization, held this weekend at Benedictine College in Atchison, Kansas. I will be talking about — surprise! — The Benedict Option, and what Christians seeking to evangelize this post-Christian world can learn from the Benedictine monks.

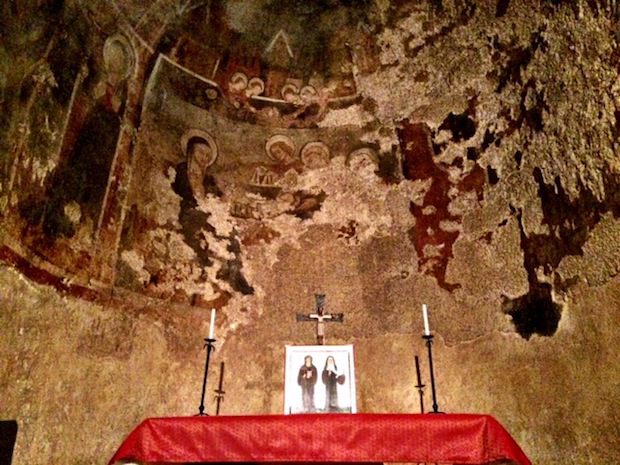

As I was writing my speech, I revisited Chapter 3 of the book, which is its heart. It’s based on my visit to the monastery at Norcia, and my interviews with some of the monks there. It is predictable, I guess, but this has been the chapter that reviewers and commenters have focused on the least — even though it’s the most important one! Here’s an excerpt:

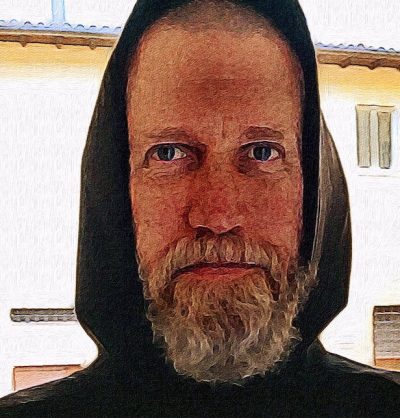

The next morning I met Father Cassian inside the monastery for a talk. He stands tall, his short hair and beard are steel-gray, and his demeanor is serious and, well, monklike. But when he speaks, in his gentle baritone, you feel as if you are talking to your own father. Father Cassian speaks warmly and powerfully of the integrity and joy of the Benedictine life, which is so different from that of our fragmented modern world.

Though the monks here have rejected the world, “there’s not just a no; there’s a yes too,” Father Cassian says. “It’s both that we reject what is not life-giving, and that we build something new. And we spend a lot of time in the rebuilding, and people see that too, which is why people flock to the monastery. We have so much involvement with guests and pilgrims that it’s exhausting. But that is what we do. We are rebuilding. That’s the yes that people have to hear about.”

Rebuilding what? I asked.

“To use Pope Benedict’s phrase, which he repeated many times, the Western world today lives as though God does not exist,” he says. “I think that’s true. Fragmentation, fear, disorientation, drifting—those are widely diffused characteristics of our society.”

Yes, I thought, this is exactly right. When we lost our Christian religion in modernity, we lost the thing that bound ourselves together and to our neighbors and anchored us in both the eternal and the temporal orders. We are adrift in liquid modernity, with no direction home.

And this monk was telling me that he and his brothers in the

monastery saw themselves as working on the restoration of Christian belief and Christian culture. How very Benedictine. I leaned in to hear more.

This monastery, Father Cassian explained, and the life of prayer within it, exist as a sign of contradiction to the modern world. The guardrails have disappeared, and the world risks careering off a cliff, but we are so captured by the lights and motion of modern life that we don’t recognize the danger. The forces of dissolution from popular culture are too great for individuals or families, to resist on their own. We need to embed ourselves in stable communities of faith.

Benedict’s Rule is a detailed set of instructions for how to organize and govern a monastic community, in which monks (and separately, nuns) live together in poverty and chastity. That is common to all monastic living, but Benedict’s Rule adds three distinct vows: obedience, stability (fidelity to the same monastic community until death), and conversion of life, which means dedicating oneself to the lifelong work of deepening repentance. The Rule also includes directions for dividing each day into periods of prayer, work, and reading of Scripture and other sacred texts. The saint taught his followers how to live apart from the world, but also how treat pilgrims and strangers who come to the monastery.

Far from being a way of life for the strong and disciplined, Benedict’s Rule was for the ordinary and weak, to help them grow stronger in faith. When Benedict began forming his monasteries, it was common practice for monastics to adopt a written rule of life, and Benedict’s Rule was a simplified and (though it seems quite rigorous to us) softened version of an earlier rule. Benedict had a noteworthy sense of compassion for human frailty, saying in the prologue to the Rule that he hoped to introduce “nothing harsh and burdensome” but only to be strict enough to strengthen the hearts of the brothers “to run the way of God’s commandments with unspeakable sweetness and love.” He instructed his abbots to govern as strong but compassionate fathers, and not to burden the brothers under his authority with things they are not strong enough to handle.

For example, in his chapter giving the order of manual labor, Benedict says, “Let all things be done with moderation, however, for the sake of the faint-hearted.” This is characteristic of Benedict’s wisdom. He did not want to break his spiritual sons; he wanted to build them up.

Despite the very specific instructions found in the Rule, it’s not a checklist for legalism. “The purpose of the Rule is to free you. That’s a paradox that people don’t grasp readily,” Father Cassian said.

If you have a field covered with water because of poor drainage, he explained, crops either won’t grow there, or they will rot. If you don’t drain it, you will have a swamp and disease. But if you can dig a drainage channel, the field will become healthy and useful. What’s more, once the water becomes contained within the walls of the channel, it will flow with force and can accomplish things.

“A Rule works that way, to channel your spiritual energy, your work, your activity, so that you’re able to accomplish something,” Father Cassian said.

“Monastic life is very plain,” he continued. “People from the outside perhaps have a romantic vision, perhaps what they see on television, of monks sort of floating around the cloister. There is that, and that’s attractive, but basically, monks get up in the morning, they pray, they do their work, they pray some more. They eat, they pray, they do some more work, they pray some more, and then they go to bed. It’s rather plain, just like most people. The genius of Saint Benedict is to find the presence of God in everyday life.”

People who are anxious, confused, and looking for answers are quick to search for solutions in the pages of books or on the Internet, looking for that “killer app” that will make everything right again. The Rule tells us: No, it’s not like that. You can achieve the peace and order you seek only by making a place within your heart and within your daily life for the grace of God to take root. Divine grace is freely given, but God will not force us to receive it. It takes constant effort on our part to get out of God’s way and let His grace heal us and change us. To this end, what we think does not matter as much as what we do—and how faithfully we do it.

A man who wants to get in shape and has read the best bodybuilding books will get nowhere unless he applies that knowledge in eating healthy food and working out daily. That takes sustained willpower. In time, if he’s faithful to the practices necessary to achieve his goal, the man will start to love eating well and exercising so much that he is not pushed toward doing so by willpower but rather drawn to it by love. He will have trained his heart to desire the good.

So too with the spiritual life. Right belief (orthodoxy) is essential, but holding the correct doctrines in your mind does you little good if your heart—the seat of the will—remains unconverted. That requires putting those right beliefs into action through right practice (orthopraxy), which over time achieves the goal Paul set for Timothy when he commanded him to “discipline yourself for the purpose of godliness” (1 Timothy 4:7).

The author of 2 Peter explains well the way the mind, the heart, and the body work in harmony for spiritual growth:

Now for this very reason also, applying all diligence, in your faith supply moral excellence, and in your moral excellence, knowledge, and in your knowledge, self-control, and in your self-control, perseverance, and in your perseverance, godliness, and in your godliness, brotherly kindness, and in your brotherly kindness, love. For if these qualities are yours and are increasing, they render you neither useless nor unfruitful in the true knowledge of our Lord Jesus Christ. (2 Peter 1:5-8)

Thought it quotes Scripture in nearly every one of its short chapters, the Rule is not the Gospel. It is a proven strategy for living the Gospel in an intensely Christian way. It is an instruction manual for how to form one’s life around the service of Jesus Christ, within a strong community. It is not a collection of theological maxims but a manual of practices through which believers can structure their lives around prayer, the Word of God, and the ever-deepening awareness that, as the saint says, “the divine presence is everywhere, and that ‘the eyes of the Lord are looking on the good and evil in every place’ (Proverbs 15:3).”

The Rule is for monastics, obviously, but its teachings are plain enough to be adapted by lay Christians for their own use. It provides a guide to serious and sustained Christian living in a fashion that reorders us interiorly, bringing together what is scattered within our own hearts and orienting it to prayer. If applied effectively, it disciplines the life we share with others, breaking down barriers that keep the love of God from passing among us, and makes us more resilient without hardening our hearts.

We are not trying to repeal seven hundred years of history, as if that were possible. Nor are we trying to save the West. We are only trying to build a Christian way of life that stands as an island of sanctity and stability amid the high tide of liquid modernity. We are not looking to create heaven on earth; we are simply looking for a way to be strong in faith through a time of great testing. The Rule, with its vision of an ordered life centered around Christ and the practices it prescribes to deepen our conversion, can help us achieve that goal.

At its core, the Benedict Option is not really about starting new schools, or changing our political engagement, or any of the other things I write about in the book (though they are important). No, the Benedict Option is about what I write in this passage: establishing a strong, disciplined, authentically Christian way of life that makes God present in all that we do, and draws us closer to Him. If this is not what you seek, the Benedict Option is in vain.

Next week, I travel to the University of Colorado at Boulder to give a Benedict Option talk. I’ll be there on Wednesday April 5 from 6 to 8 pm. The talk is free, but you need to register here. I hope to see you there.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.