Dante, You Dog

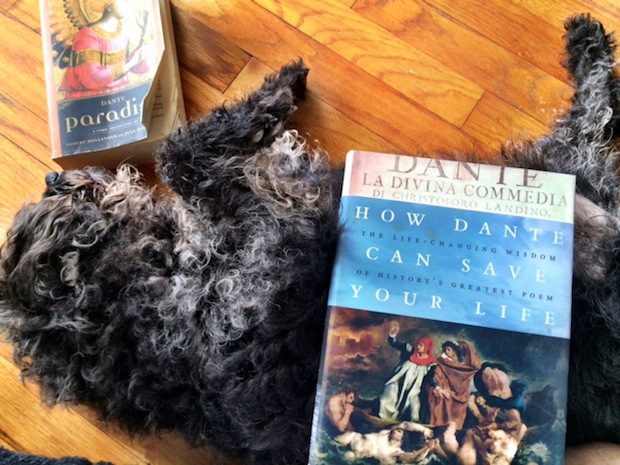

That black fuzzball you see above is my little dog Roscoe, who is bored to death by Dante. I do not expect him to give a rat’s rear end about my book, which sits upon his fat belly. You, however, will, I hope, pre-order it. It will be out on April 14.

It is well that Roscoe maintains his indifferent to the Poet, for the Poet apparently did not like dogs. Alberto Manguel:

Of all the insults and derogatory comparisons Dante uses in the Commedia on both lost souls and evil demons, one recurs throughout. The wrathful, according to Virgil, are all “dogs.” From then on, in his travel notes through the kingdom of the dead, Dante echoes his master’s ancient vocabulary. Thus, Dante tells us that the wasteful in the seventh circle are pursued by “famished and fast black bitches”; the burning usurers running under the rain of fire behave “like dogs who in the summer fight off fleas and flies with their paws and maw”; a demon who pursues a barrater is like “a mastiff let loose,” and other demons are like “dogs hunting a poor beggar” and crueler than “the dog with the hare it has caught.” Hecuba’s cry of pain is demeaned as a bark “just like a dog”; Dante apprehends the “doglike faces” of the traitors trapped in the ice of Caïna, the unrepentant Bocca “barking” like a tortured dog, and Count Ugolino gnawing at the skull of Cardinal Ruggiero “with his teeth,/which as a dog’s were strong against the bone.”

Angry, greedy, savage, mad, cruel: these are the qualities that Dante seems to see in dogs and applies to the inhabitants of Hell. To call a person a “dog” is a common and uninspired insult in almost every language, including, of course, the Italian spoken in Dante’s thirteenth- and fourteenth-century Tuscany. But mere commonplaces are absent in Dante: when he uses an ordinary expression, it no longer reads as ordinary. The dogs in the Commedia carry connotations other than the merely insulting, but overriding them all is the suggestion of something infamous and despicable. This relentlessness demands a question.

And yet, at the end of this delightful essay, Manguel has turned Dante not only into a dog lover, but a dog, saying that the qualities the Poet gives to his eponymous character in the Commedia has all the qualities we admire in dogs. I can see that, if I squint.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.