Saying The C-Word

When I moved to Washington, DC, in 1992, I was in the process of converting to Catholicism. I remember well that whenever religion came up in discussions with strangers outside of conservative circles, it was easier to talk about being a Catholic than being a Christian. I couldn’t explain it back then, but it’s one of those things you just absorbed if you were attentive to status markers, as you certainly had to be as an ambitious twentysomething learning the ropes in the political and media world there. Among crowds that contained liberals, using the word “Christian” in a non-pejorative sense could be a conversation-stopper. Again, I wasn’t sure why, but it’s one of those things you quickly came to understand.

In the years since then, I developed this theory that people on the Left had more respect for someone who identified as “Catholic,” as opposed to the more generic “Christian”. Part of it was intellectual snobbery (from which I suffered, I confess): you might not like Catholicism, but you couldn’t deny that the Catholic Church had produced some intellectual and cultural powerhouses in its long history. And, it was a way of setting oneself apart from the kind of Christians that some DC cosmopolitans really despised: Evangelicals and charismatics.

Part of it too was that many liberals, though no longer practicing the faith, had roots in Catholicism, and therefore an inchoate affection for it, however reduced. And if these liberals came from the Northeast, they related emotionally to Catholicism in a tribal way. To hate it outright would have been to hate themselves, to some extent. I’ve been told by Evangelical friends who grew up in Texas and the South that lots of Evangelicals are taught that Catholics are not really Christian, and that they (the Evangelicals) will in conversation among themselves speak as if the difference between Christians and Catholics was understood. A similar distinction was made by DC folks back in my time there, but wholly for social reasons.

I’m not sure that this theory fully explains the phenomenon, and in any case it is seriously outdated. Back then, the thing that most wound secular liberals up against Christians was abortion. Now it’s abortion and LGBT. I’ve lived and worked in newsrooms in several places since my DC days, and moved professionally in liberal circles. I’ve long observed that many secular liberals cannot understand global Christianity except through US culture war politics. Their grasp of Christianity, both in the US and around the world, is shockingly shallow — especially Christianity outside North America and Europe. It’s as if they regard Third World Christians as coddling little Falwells inside, just dying to get out.

So many of them can’t say the C-word: Christians. In poker, a “tell” is something that a player does that gives away what he has in his hand. Experienced players learn to read the body language of their opponents, looking for a tell — a twitchy brow, a quick downturn of the mouth, that sort of thing. It’s a tiny clue that lets you know what’s on the player’s mind. Well, the uniform Twitter use by three prominent Democratic politicians of the phrase “Easter worshippers” for dead Sri Lankan Christians was a tell. It’s likely that none of those politicians — H. Clinton, Obama, and Julian Castro — wrote those condolence tweets; prominent politicians usually have someone else managing their Twitter accounts (Trump is a notable exception). What probably happened is that someone at Democratic messaging central sent out an advisory that the unusual phrase “Easter worshippers” was the preferred word for “Christian” — this, perhaps on the grounds that it would be less likely to feed “Islamophobia.” The now-notorious Washington Post story about how all those dead Sri Lankan Christians so inconsiderately gave the European far-right something to gripe about is a related tell.

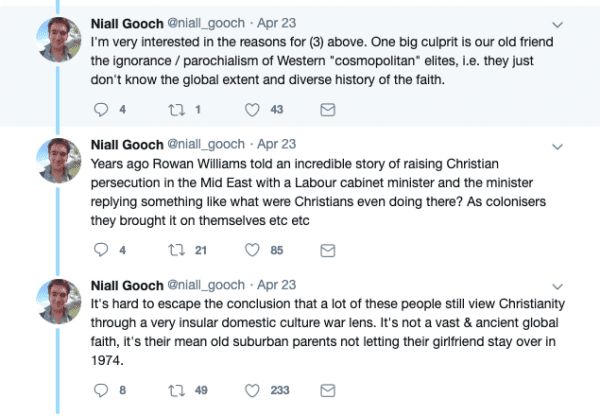

My English Catholic friend Niall Gooch tweets (“(3) above” is “Western elites do seem extremely uninterested in anti-Christian persecution”:

To be fair, we American Christians can be incredibly ignorant ourselves about the faith outside our own framework. I had been Christian for more than a few years before it really began to sink in that Arabs were practicing the Christian faith back when my own ancestors in northern Europe were still pagans. To this day I cringe when I hear Evangelicals talk about how excited they are to bring the Gospel to Russia, which has been worshipping Jesus Christ officially since the year 988. I understand the desire to bring Evangelical Christianity to a non-Evangelical part of the world, and don’t fault Evangelicals for doing so, but it’s just … weird, at best, to speak as if no one in these countries had ever heard of Jesus. This is a version of the same thing we rightly complain about when secular liberals do it: acting like the only real Jesus is American Jesus.

Anyway, Ross Douthat wrote a really good column about all this out of the Sri Lanka bombings. Douthat says that liberals have a strange and contradictory relationship to Christianity, treating it “as something that really exists only in relationship to its own secularized humanitarianism, either as a tamed and therefore useful chaplaincy or as an embarrassing, in-need-of-correction uncle.” More:

But if the equation of traditional Christianity with privilege has some relevance to the actual Euro-American situation, when applied globally it’s a gross category error. And so the main victims of Western liberalism’s peculiar relationship to its Christian heritage aren’t put-upon traditionalists in the West; they’re Christians like the murdered first communicants in Sri Lanka, or the jailed pastors in China, or the Coptic martyrs of North Africa, or any of the millions of non-Western Christians who live under constant threat of persecution.

One of the basic facts of contemporary religious history is that Christians around the world are persecuted on an extraordinary scale — by mobs and pogroms in India, jihadists and United States-allied governments in the Muslim world, secular totalitarians in China and North Korea. Yet as an era-defining reality rather than an episodic phenomenon this reality is barely visible in the Western media, and rarely called by name and addressed head-on by Western governments and humanitarian institutions. (“Islamophobia” looms large; talk of “Christophobia” is almost nonexistent.)

This absence reflects, once again, the complex combination of liberal impulses toward Christianity. There is a fear that any special focus on Christians will vindicate the jihadist narrative of a clash of civilizations. There is a certain ignorance of Christianity’s enduringly and increasingly global form, an inability to see Christianity as anything save a reactionary foe or a useful supplement to liberalism. There is a fear that narratives of global Christian persecution will somehow help the conservative side of Western culture wars. (“Sri Lanka church bombings stoke far-right anger in the West” ran the headline of a worried Washington Post “analysis,” as though the most worrying consequence of dead Christians in South Asia were angry conservatives in America.) And there is a sense of Christianity as somehow still “our” religion, the dogmas discarded but the emphasis on self-abnegation retained — albeit in a strange fashion that ends, as John O’Sullivan put it recently, by taking “the good Samaritan to be a parable of why Christians should be the last people to be helped.”

In France, the Archbishop of Paris has noted with frustration that President Macron has de-emphasized the fact that the burned cathedral is a Catholic building. Excerpt:

“Yes, probably, I think it’s because of a misunderstanding of the nature of secularity, which simply means the distinctness of [temporal] power. But that doesn’t prevent him from saying what we are, and what we are going through. This cathedral was built in the name of Christ. It is an addition of stones inhabited by a spirit. It is not a functional building. Some sculptures are in places you can’t see: that is truly for something greater and more beautiful,” he said.

Msgr Aupetit also recalled the multiple aggressions against churches over the last months: “There are about three attacks per day. We shouldn’t generalize about anti-Christian hate but there is a lack of respect regarding sacred things.”

In de-christianized France, an increasing proportion of the native population no longer has any idea about Catholicism, its symbols, its rites, and its saints.

Interior minister Christophe Castaner made an official declaration on Wednesday morning in front of Notre Dame, saying: “Notre Dame is not a cathedral.” He added: “It is our common, it is what assembles us, it is our strength, it is our history.”

“That’s not untrue,” remarked editorialist Gabrielle Cluzel on Boulevard Voltaire. “Except that obviously, it’s also all of that BECAUSE it’s a cathedral.”

Bénédicte Le Chatelier, a journalist for the news TV station LCI, went a step farther. She commented live on the fire, saying: “Notre Dame is not a religious location, but the Catholics continue appropriating it to themselves.”

Can you imagine? Seriously, can you?

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.