Living With The Body

Quillette is so invaluable. Where else would you be able to read this amazing warning tale by Scott Newgent, a female-to-male transsexual who is happy living as a male, but who says the overwhelming number of websites and media outlets selling trans to unhappy teenagers are lying to those kids and their families about what’s ahead. Excerpts:

Anyone going through this is in store for a brutal process. Yet we now have thousands of naïve parents walking their children into gender-treatment centers, often based on Internet-peddled narratives that present the transition experience through a gauzy rainbow lens. Many transition therapies are still in an experimental phase—as you will learn if you become sick during or after these treatments.

During my own transition, I had seven surgeries. I also had a massive pulmonary embolism, a helicopter life-flight ride, an emergency ambulance ride, a stress-induced heart attack, sepsis, a 17-month recurring infection due to using the wrong skin during a (failed) phalloplasty, 16 rounds of antibiotics, three weeks of daily IV antibiotics, the loss of all my hair, (only partially successful) arm reconstructive surgery, permanent lung and heart damage, a cut bladder, insomnia-induced hallucinations—oh and frequent loss of consciousness due to pain from the hair on the inside of my urethra. All this led to a form of PTSD that made me a prisoner in my apartment for a year. Between me and my insurance company, medical expenses exceeded $900,000.

During these 17 months of agony, I couldn’t get a urologist to help me. They didn’t feel comfortable taking me on as a patient—since the phalloplasty, like much of the transition process, is experimental. “Could you go back to the original surgeon?” they suggested.

Whenever you question the maximalist activist line on trans affirmation, you are directed to The World Professional Association for Transgender Health (or WPATH) as a reference. But much of what you find there consists of vague phrases such as “up to doctor’s discretion.” Several lawyers suggested I had a slam-dunk medical-malpractice case—until they realized that trans health doesn’t really have a justiciable baseline. As a result, treatment often is subpar, as I have experienced first-hand.

Newgent believes that transition ought to be restricted to adults, who, unlike children and minors, have the capacity to make these decisions:

For parents, I would say this: It is simply not your right or duty to decide to medically transition your child. Remove that burden from your mind. Medical transition is for adults. The negatives associated with medical transition are vast, and you won’t be the one who lives with the consequences. It will be your child. If your child tells you they will kill themselves if you do not allow them to medically transition (perhaps following a script he or she is provided on Reddit or Tumblr), take them to the hospital so they can be treated for suicidal ideation. Suicidal ideation and seeking transition are separate issues, so separate them.

We talk a lot about oppression and marginalization. Well, I’m one of the people who’s been oppressed and marginalized—more so now that I have outed myself so that I can try to help others. The least you can do is pay attention to my message.

Read it all. It’s very brave. Newgent will be set upon by trans activists.

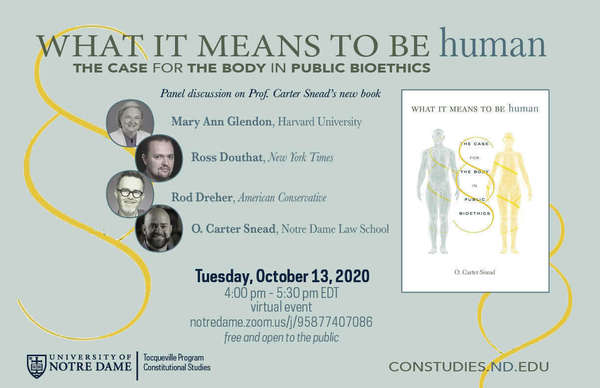

Later today I will be participating in an online Zoom discussion alongside Harvard’s Mary Ann Glendon and the New York Times‘s Ross Douthat, in which we discuss a new book by O. Carter Snead of Notre Dame: What It Means To Be Human: The Case For the Body in Public Ethics.

Details about the event can be found here. If you want to join the seminar (which is free and open to the public), the Zoom address is: notredame.zoom.us/j/95877407086

I don’t want to give away here too much of what I’m going to say in my comments, but I’ll say this: Snead’s great new book really does illuminate how far we have gone down a dark road in our society. The three areas he focuses on are abortion, assisted reproduction, and end of life issues. Transgenderism never comes up, but it easily could have, as the thing all these phenomena have in common is a certain way of regarding the body. The word “God” never comes up in this book, and doesn’t need to for Snead to make his case. I finished the book with a greater understanding of the critiques I have been making for years about our social order. It might even be accurate to say that what is wrong with us is less about losing God than about losing Man — though I would say that having first lost God, we could not help but lose Man.

The core of the book is about the bioethics results from the anthropology nearly everyone has come to accept in the modern world. Snead says that our approach to bioethics depends on “an image of the human being that does not reflect the lived experience of embodied human reality in all its complexity.

Instead, it relies on a partial and incomplete vision of human identity that closely tracks what both sociologist Robert Bellah and philosopher Charles Taylor have identified as “expressive individualism,” in which persons are conceived merely as atomized individual wills whose highest flourishing consists in interrogating the interior depths of the self in order to express and freely follow the original truths discovered therein toward one’s self-invented destiny. Expressive individualism, understood in this sense, equates being fully human with finding the unique truth within ourselves and freely constructing our individual lives to reflect it.

More Snead:

People thus encounter one another as collaborative or contending wills, pursuing their own individual goals. Claims of unchosen obligations and unearned privileges are unintelligible within this framework. In this paradigm, the goods of autonomy and self-determination enjoy pride of place among ethical and legal principles. Law and government exist chiefly to create the conditions of freedom to pursue one’s invented future, unmolested by others and perhaps even unimpeded by natural limits.

Snead goes on to say

What is needed, and what this book offers, is an anthropological corrective, an augmentation to the foundations of American public bioethics. To govern ourselves wisely, justly, and humanely, we must begin by remembering the body and its meaning for the creation and implementation of law and policy.

Again, Snead’s arguments in the book are not based on religious claims. Rather, he talks about what it means to live as creatures with bodies. As it happens, I am deep into a terrific new novel, Alexandria, by the English writer Paul Kingsnorth, that is about the same thing. The novel is set a thousand years into a post-apocalyptic future. I won’t give away too much, but the philosophical question at the heart of the conflict is: what does it mean to be embodied? One character speaks of the glories of bodiless existence:

I have no sex, no prejudices, no mother, no father, no family, no home, no history. Thus, I am liberated.

If we use advanced technology to rid ourselves of our bodies, the conceit goes, then we can truly be free. We are free from suffering and death only when we shed our bodies. In the novel, there are a primitive people who resist this claim — but their resistance, interestingly, is based on what can only be described as religious belief. They are not Christians — Christianity seems to have disappeared from this world — but they hold the Earth and all that is in it to be sacred, and believe that those who preach bodiless liberation are demonic. I’m about three-quarters of the way through the novel (which comes out next week), and one thing that impresses me is how none of these simple people can make a philosophical argument against the sophisticated dualists. They rest on their pagan religious beliefs, and the deep intuitions they have from their bodies.

I didn’t plan to be reading Carter Snead and Paul Kingsnorth’s books at the same time, but doing so has been a revelation to me. Snead’s book revealed to me how the Story Of Which We Find Ourselves A Part (to use Alasdair MacIntyre’s phrase, quoted by Snead) is wholly one in which nearly every narrative is built to support expressive individualism, and its core idea that you are what you desire to be. Kingsnorth’s dystopian fiction is about where that philosophy takes us — specifically, about the violence that Man does to Nature, and ultimately to himself, by using his intelligence and his technology to force the natural world, and his body, to surrender to his unfettered will.

Snead quotes Justice Anthony Kennedy’s opinion, for the Supreme Court majority, in the 1992 Casey decision reaffirming Roe v. Wade:

At the heart of liberty is the right to define one’s own concept of existence, of meaning, of the universe, and of the mystery of human life.

Embedded in this statement is the anthropology of expressive individualism. It’s the water in which we all swim. It minimizes and ultimately denies the reality of our embodied existence. Reading Carter Snead, and Paul Kingsnorth, and Scott Newgent together brings about an epiphany that makes one shudder, given how unlikely our civilization is to surrender this, its central myth. As the evolutionary biologist Joseph Henrich explains in his wonderful new book The WEIRDest People In The World, this is not a belief that emerged in the 1960s, or even in the twentieth century. It has been building in the West for centuries.

But it’s a lie. The world is not like that. Seems to me that we need both critiques like Carter Snead’s and storytelling like Paul Kingsnorth’s, working together to help us remember who we are. We are embodied creatures. We are made to love and to suffer, together. This is the testimony not only of holy books, but of our bodies.

Anyway, I hope to see you on Zoom later this afternoon for the seminar.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.