Third-World Burkeans

A national broadcast journalist told me on Friday, “You have the most intelligent commenters anywhere.” This e-mail, from “London Harry” — a 17-year old British student — justifies that verdict. I post it with his permission. What an interesting set of observations! Here’s London Harry’s original post — his “political mental map,” in which he talks about having been born in Japan to a white British father and an Anglo-Indian mother, and moving back to the UK for his and his brother’s education.

Harry e-mailed today to say:

Thanks so much for starting the Mental Maps series. I’ve really appreciated reading your readers’ responses to my contribution, and am presently stuffed with food for thought. It’s also been very interesting to encounter Mental Maps from other Britons. They’ve been a much-needed reminder that in our age of endless high-political squabbling and Twitterstorms, thoughtfulness and self-examination survive among private citizens of all classes and ideological leanings.

I write to offer a few thoughts on some questions of cultural difference which were thrown up during the discussion of my Map. I hadn’t previously thought of my skin colour as being an important conditioning factor in the formation of my politics, but putting pen to paper has made me realise how much I’ve been predisposed against the racial left by my daily interactions with loving people from white backgrounds. I’d probably have a very different take on things if I was a working-class West Indian or Pakistani boy my age in Brixton or Camberwell.

These questions of cultural difference and ‘the Other’ are dark and disturbing for Britons because they demand engagement with dark and disturbing aspects of our past: the persecution of Jews and Catholics; the brutal excesses of the British Empire; the oppression of Ireland and the Highland Clearances; the transatlantic slave trade. For the moderate majority of Britons, they are difficult to reconcile with our self-conception as the midwives of common-law justice and parliamentary democracy because there exists no liberal or conservative intellectual tradition which deals with them. As such, so many of us fall back on the idle assumption that these are not politically or morally important events, and that those commentators who seek to address them are ideologically-driven grievance-peddlers. They aren’t. No brown or black Briton who seriously wants to understand their personal hinterland can avoid comparing Britain to the old country, whether it is India or Jamaica or Pakistan. That comparison necessitates some understanding of why almost all postcolonial nations have sunk back into violent racial and sectarian politics and economic and cultural dysfunction since their independence.

The fundamental issue is the role played by British colonists in liquefying these countries’ political foundations. In the absence of a postcolonial liberalism or postcolonial conservatism, three intellectually flimsy and morally objectionable schools of thought rule the roost.

The first is the neoconservative thesis, preached by Niall Ferguson. Its logic is attractively simple. The normative political traditions of Britain – the rule of law, parliamentary democracy – and its social innovations – medicine, education, modern logistics – are grounded in reason and goodness. To oppose their introduction to primitive extra-European countries is therefore irrational and bad. Yes, Pakistan is a mafia state with retrograde blasphemy laws and in the economic doldrums, not to mention its sponsorship of the Taliban and Al-Qaeda. Yes, it’s impossible for middle- and working-class Indians to make it into the Westernised professional class without paying bribes, which in any case will do nothing to protect their daughters from gang-rapists on public transport. Yes, an unholy alliance between Jamaica’s tiers-mondiste [Third Worldist — RD] politicians and its gangland barons has driven the populace they rule into drug-addled acquiescence. And yes, the British Empire did do some vaguely nasty things. But the diaspora of these countries in the West should be grateful to Britain for teaching them the ways of civilised man. It’s just common sense.

The second is the tiers-mondiste thesis, advanced by those on the far-left who think history boils down to an all-consuming struggle between the capitalist West and various oppressed peoples in the Third World. In this telling the atrocities of Empire show bourgeois white liberals’ talk of freedom, humanism etc. to be mere ideology, empty abstractions serving as instruments of geopolitical oppression. What the proponents of ‘imperialism’ were always really interested in was money and power. Small wonder the Third World is such a mess today. The proponents of this thesis naturally have little to say about how their rhetoric has been appropriated by postcolonial despots, or about the retrograde aspects of Third World religion and society which have nothing to do with their colonial past. In any case, the idea that liberty and medicine don’t actually mean anything should probably be discouraged in an age of political instability.

The third is the realist thesis. This concurs with the neoconservative thesis that empire was at root a humanitarian enterprise encouraged by worldwide strategic competition between European powers – never mind slavery. Yet the tragedy of empire lies not in its brutality – mere means-to-an-end – but in the failure of British statesmen to realise that these countries were irredeemably savage, as the postcolonial present attests. As the neoconservative thesis is rightly dismembered by the left, the intellectual right is increasingly falling back on this interpretation. But the assumption that the morals and politics of men and women are determined entirely by which of the world’s irreducibly different cultures they originate from is nihilistic in its denial of individual moral agency. And if Britain withdraws from all engagement with the outside world for fear of wasting its time, neither Britain nor the outside world will be the better for it.

If these three interpretations are wrong, why have conservatives and liberals not come up with anything better? I think the answer lies in cultural change. For the whole of the Cold War ethnic minorities did not have enough political agency for any politician to bother discussing our colonial past, so forty years were wasted. In the Nineties, when the end-of-history mentality and postmodern ironical posturing were in the ascendancy, would-be postcolonial Solzhenitsyns were either ignored or sniggered at. Why drag up the past when the future looked so bright?

And then something weird happened to Britain. In the wake of 9/11, Iraq, 7/7 and the 2008 crash, Britons got serious. Sincerity became the new cool. Tony Blair, David Cameron, George Osborne and Nigel Farage now lie mangled at the bottom of the greasy pole: no-one likes public-school jokers any more. Comedy has stopped being funny, at least on the BBC. The laddishness and double-entendres of Nineties and Noughties popular culture has given way to earnestness and debased sentimentality (see The Great British Bake Off, if you can bear it). Politicians who treat everything with epic piety are rewarded with party leaderships. And our politics is all the worse for it. Now that everyone is utterly convinced of the fundamental goodness of their own hearts – a conviction unacceptable to true conservatives – compromise and cooperation between different political tribes is unheard of. And because anything other than total ‘authenticity’ is haram, our culture has become childish both in its vulgarity and its naivety. No politician or intellectual thrown up by the New Sincerity has the curiosity or comprehension of man’s moral complexity to engage with the darkest happenings in British history. The neoconservative thesis and the realist thesis are rejected out of hand because notions of cultural superiority aren’t very nice, and the tiers-mondiste thesis is ignored because doubting the sincerity of the West’s commitment to liberal traditions or the very value of those traditions just seems so cynical. The irony is that it is precisely because ethnic minorities behold a hellscape of hypocrisy, idiocy and ceaseless sanctimony every day that they choose not to ‘integrate’, and justify their self-imposed segregation with the tiers-mondiste thesis.

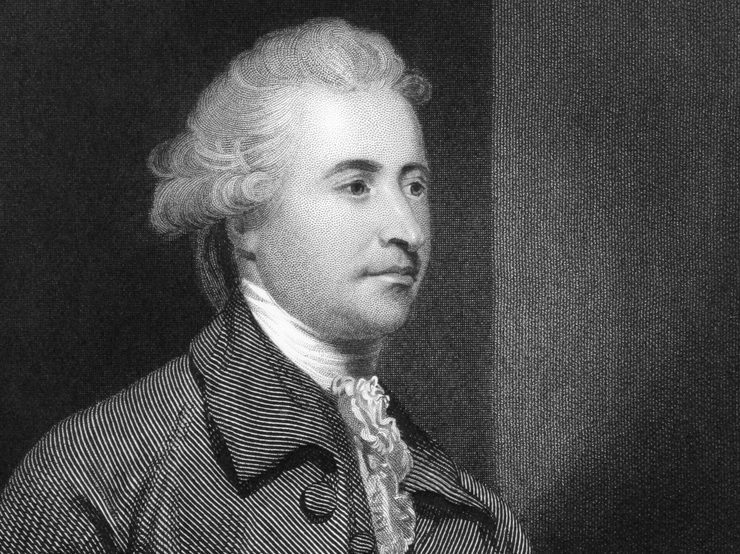

Yet I detect a way out. In recent years ethnic-minority scholars like Uday Mehta and Ed Husain have sought to approach questions of cultural difference through a Burkean lens. These Third World Burkeans deplore the colonial project not because of its failure to impose liberalism on the Third World but because of its success. Just as the Jacobins were wrong to tear down the pillars of the French state in the hope of raising Utopia from the rubble, so British colonists were wrong to annihilate ancient monarchies the world over in the name of progressive enlightenment. This is not to vilify liberal ideas, qua the tiers-mondistes, or to vilify the peoples of the Third World, qua the realists. And it is certainly not to fecklessly excuse colonial violence, qua the neoconservatives. It is simply to acknowledge that it is far easier to upset a political order than to create one, and that good intentions are not enough. Moreover, violently imposing universal ideals on different particularities is inimical to the love of mystery and tradition so central to conservatism. In this, the Third World Burkeans have a venerable ally in the steadfast enemy of imperial expansion Edmund Burke. As ethnic minorities in Britain gain greater political and cultural agency, the colonial question will eventually have to be answered. The only way for brown, black and white people to do this without stepping into the quagmire of anti-Western radicalism or pro-Western jingoism is by journeying back to Burke.

Thanks, Harry. Thoughts, readers? Hector St. Clare, Harry’s comments beg for a response from you.

Here’s my thought: The Spectator ought to be cultivating Harry as a writer. A man who can write and think like that at 17 has a bright future. I’m going to do what I can to connect them to him.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.