Bishop Camisasca On the Benedict Option

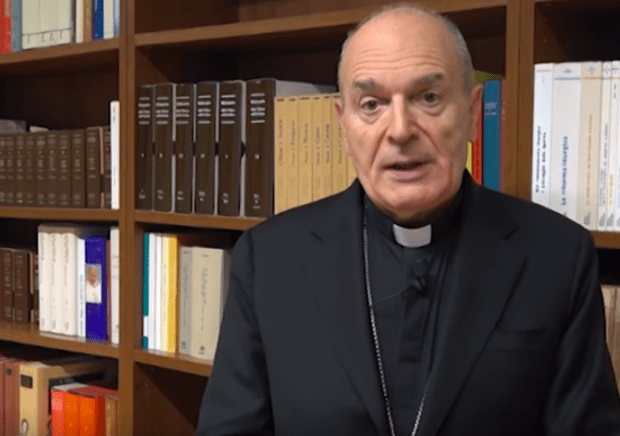

Earlier this autumn, when I was in Italy on the Benedict Option book tour, I was at a panel discussion in Milan in which Monsignor Massimo Camisasca, Roman Catholic bishop of Reggio Emilia-Guastalla, gave a talk about the book. It was a very thoughtful reflection. Over the weekend, Italian friends sent me an English translation of his remarks. I reproduce them below:

The great value of Rod Dreher’s book The Benedict Option is that it proposes a “comprehensive reflection” on our times, on the basis of which he offers a potential answer to the question: what historical form might the reality of the Church take in the contemporary context? Which form is most true, effective, and in keeping with her mission?

The book thus speaks to us of the form of the ecclesia as a people, as quahal, a collective that is definitive and yet always unfulfilled, like the body of Christ which, according to Paul, is both already fully realized and yet must always be completed (Eph 1:3-23) through the works of the apostles, the fathers and mothers who participate in the maternity and paternity of God.

What is the essential form of God’s Church? This is not a new question. Rather, it is one that has been dutifully present though all the twenty centuries of Christian history and for at least ten centuries of the story of the people of Israel before. But we must ask it, just as we must wait for God to provide the answer, which can never be wholly anticipated by human beings. Indeed, God answers the question of the historical expression of the permanent form of the Covenant in an impulse or suggestion which he puts to the freedom of the baptized. The Lord addresses it to them through the events of the history of the world (exactly as he did to Israel, before Christ, through Egypt, Assyria, Babylon, and so on) and the events of salvation history (the tensions between its kings and its profits, its faithfulness and its betrayals). And, ultimately he addresses it to them through the adventure of holiness. This adventure is never entirely at the disposition of human beings, even if it is not indifferent to the instance of freedom. At base, the answer to our question

(“What is the essential form of God’s Church?”) springs from the encounter of two infinites in time: the freedom of God and human freedom. Benedict is neither predictable nor programmable, just like Augustine before him, and before that Anthony, Basil, and Pachomius, and afterwards Leo and Gregory the Great. It is a matter of the Spirit’s suggestions being embraced by holiness, by the simple or complex genius of people like us, even if they were giants. But their stature becomes clear only later, sometimes only after centuries have passed.

***

To avoid the risk of speaking without saying anything, I would like to attempt to point out a path: what is the suggestion the Spirit is making to us, to me, today, through my fathers?

Everything can be found within the permanent journey of reformation of the church community, which begins within its daily seed, from the reformation of hearts. Reform, the birth of a new form, begins with the reformation of the heart, which changes form the moment it no longer focuses on itself, but on another. True reform is the displacement of our personal being in God.

***

I do not think we can, nor should we, speak of a historical form that can be applied in the same way on every continent where Catholica [sic] lives. Since its inception, the Church has existed in a multitude of different languages and cultures, starting with the pluralism of the original community (Petrine, Pauline, Johannine, etc.), the pluralism of the charisms (missionaries, evangelizers, and prophets), and the pluralism of the Gospels and the canonical texts. This is the pluralism of the innumerable facets of the one face of Christ, which may never be pared down to just one. The person of Jesus is, indeed, infinitely knowable, and each of us may only grasp one portion of his mystery. But what

distinguished the Church at its origins was the awareness that none could do without the others. The whole, the One in Trinitarian form, that is, the One of the Church as faith and charity, always precedes the different communities. They are not a part of the One, but a reflection of it.

Every Church, or rather, every community that comes from the Eucharist and, therefore, from the apostolic succession, is all the Church, just as every fragment of the Eucharist is the whole body of Christ, to the extent to which that community conceives of itself and lives in unity with all of Catholicism.

The form should be understood as the relationship between two foci in an ellipse: the two foci of the humanity and the divinity of Christ in the unity of his Person, at the right hand of the Father and in the mud of history.

***

We cannot reflect on the form of the Church without knowing and forming a judgment about the historical period in which we live. So what are the features of our time? Should we approach it with feelings of sympathy or of rejection?

I believe that the most fruitful approach today, in the face of the dramatic and new issues that surround us (posed by the secularized society, the globalized word, post-modernity and transhumanism), must be both positive and constructive. Our principal attention must not linger on condemnation, but on the positive attraction that is operated by the lives of people who live the faith. That is, we should focus on a proposal. When we start from the positivity of a proposal, we may discover just how transient, at times diabolically so, everything is that later, in the light of God, becomes condemned.

In this context, I do not think modernity is purely negative. Like every historical period, it is a weaving together of good and evil. Think of the parable of the weeds and the wheat (see Mt 13:24-30). The teaching of Benedict XVI has thoroughly laid out how modernity contains, together with a deep denial of Christian identity and a systematic and intentionally anti-Christian project (and anti-Catholic in particular), a call back to authentic faith. Every age tends to put parentheses around some aspects of life while underscoring others. One of the things we have received from modernity is the call to rediscover freedom, and we must not forget it.

Any reactionary idea, to the extent to which it sees goodness only in the past, forgets to project forward, and, together with being rooted in the origin, this projection forward is the necessary journey of Christian life. Indeed, Christian life is a constant weaving together of past and present toward He who is coming again.

Of course it is necessary and helpful to learn from the past. It is useful to point out and to highlight the similarities between the present time and other periods of history that came before. For example, certain parallels are clear, as Dreher’s book points out as well, between our historical moment and the end of the Roman Empire. But two epochs are never identical. Therefore, the solutions that allowed us to traverse the past can serve as a source of inspiration, but not as the model upon which to plan to live the present.

***

Now I would like to linger on a few essential experiences of Christian life in every time.

1. The liturgy: encounter with the Mystery in the humanity of the world

The Church lives as the conversion of the world to Christ. It is made up of communities, small or large, which are aware of their belonging to the one Catholica [sic]. The origin of a Christian community is always the liturgy, praise offered to the Trinity from the blood and from the excrement of the earth, but also from the light of the seas, mountains, and flowers, and of the hearts that open themselves to God, to forgiveness, to hospitality, and to brotherhood.

The Church originates as wonder before the greatness of life, before its mysteriousness and beauty, in which the humanity of Christ is reflected. The Church originates from an encounter with the Mystery, which shines through in the human and pierces it (a poem, a face, a melody, a sorrow, a loss, a wound…). This encounter is made possible by the fact that someone helps us to live, and to perceive with new eyes.

Another – who reveals himself as authority, as a father who generates, and a brother who has pity on us – opens our eyes to what we have always looked at, but have never really seen. Reality becomes a sign, without losing its substance, both beauty and discomfort.

People you did not know become essential, prayer becomes essential, singing, giving praise, silence, meditation, and reading become essential, as does having a guide who helps you in your new commitment your life and the lives of others.

In reality, everything is generated by the Spirit and by the currentness of the mysteries of the life of Christ. He takes things and turns them into his sacraments. It is he who acts, joining together a community of people who used to be strangers and are now familiar because God became familiar to them.

The community originates as liturgy. Certainly this includes the Sunday celebration, as its summit, or the Psalms of the Liturgy of the Hours, but the community is never reduced to a prayer that isolates or distances it from life and from other people. In the liturgy is all the allure of heaven and earth. For this reason the liturgy cannot be secularized without being trivialized, nor can it be permitted to become the place where many individual people dialogue with God, gathered together at random.

2. Community and authority

A second aspect. The Church is a universal community, a single people to whom all the peoples of the world are called, one body, just as the faith is one and charity is one. But as the body has many parts, so the Church, by analogy, is made up of many communities. This is because faith must be lived out in proximal relationships, in which the warmth of brotherhood and the salt of change, the light of forgiveness and the weight of difference, may all be experienced.

This is the historical principal at the origin of dioceses and parishes (with a different theological weight, of course), communities of consecrated virgins, families, local associations, all the various communities who live in common, religious communities, and so on.

In the at times profound diversity of its historical expressions, the Church has always required at least a minimal expression of communal life: the Sunday Mass, sharing one another’s needs, and participation in unity of thought and action in necessary things. Individualism, which has been on the rise over the past four centuries, has eaten away the knowledge of unity and its expressions. But all of these issues now demand our attention again, with new and radical urgency.

A Christian community is a guided community. It comes from on high, from God, to root itself on the earth, penetrating into the details of human life. The ultimate guide is, therefore, always a priest in relationship with the bishop, who must see himself as his emissary. Educational guides may be priests or a laypersons, male or female, young or old. But Christian life does not exist without a link to the otherness of God. Certainly, any authority may fall into authoritarianism, arbitrariness, or the pure exercise of power. But this in no way detracts from its necessity. We need fathers and mothers who know how to guide us loving us, and who love us enough to correct us, even harshly if necessary, always helping us to walk in the steps of Christ while we walk in time under the guidance of human beings. The scandal of the eternal in time is one that cannot be avoided. Is he not the carpenter’s son? (Mt 13:55).

3. The Church and the world

The Church’s reason for being does not come from itself, just as the light of the moon does not come from itself. This fact is highlighted today, and rightly so. The light is Christ. But the Church is necessary, too. Without the moon, the dark night would be impenetrable.

Christ, lumen gentium, said: You are the light of the world (Mt 5:14). The Church is not other than Christ, whose body it is. It is not other than the Kingdom, of which it is the beginnings. Can we not also say that the Church is not other than the world? Yes and no.

I prefer to think, as I have already said above, that the Church is the world converting to Christ. For this reason the Church exists in a twofold movement, of judgment on the world (the ruler of this world has been condemned – Jn 16:11) and objection to its criteria, goals, and designs (they do not belong to the world any more than I belong to the world – Jn 17:14), and of salvation, which reveals Christ and the Church as that thing which human beings hope for from their depths (I did not come to condemn the world but to save the world – Jn 12:47). The world is the object of God’s vast love (God so loved the world that he gave his only Son – Jn 3:16). This two-fold movement is (or ought to be) permanent in the history of the Church. In reality, it is a single movement of light and of salt, of testimony that attracts and causes the scales fall from the eyes of the old.

In two thousand years this journey has played out around two experiences, which are central in the life of Jesus: virginity and martyrdom.

Today virginity means rediscovering sexuality and affection, the two great, weak links of our times.

It means sexuality returning to be the marvelous discovery of another person, in their

complementarity and difference from me. Exercising sexuality in a way that refuses to reduce it to pure physical pleasure, but goes back to being a journey of awareness (albeit inevitably marked by the falls of our smallness), of fruitful ecstasy, with the same sacrifice and distance that every rebirth always requires.

Virginity and martyrdom mean taking a new path that integrates silence, study, reading, meditation, work, and the use of technology. It is a path that is almost entirely unwritten. It is not impossible, although it isn’t easy. In the last two chapters of his book, Rod Dreher offers some reflections on sexuality and the use of technology, attempting to identify paths that allow us to live out eros in a more human way, and our relationship with machines in a more free way. His reflections are valuable and easy to agree with. But these topics, due to their extreme complexity, must necessarily remain open, awaiting further and more detailed consideration.

Virginity and martyrdom are the defense of burgeoning lives from abortion, the defense of fragile lives from euthanasia, the defense of the poor, of the forgotten. Charity reveals the monstrosity of ideologies and of the economy when its purpose is amassing wealth for the few.

Only virginity and communion can sustain a community in martyrdom, making it aware of the stakes and joyful in the patient knowledge of victory.

***

Our Christian communities, in order to safeguard and live the faith to the fullest in the times in which we live, are in need of a monastic framework, the basic coordinates of which I sketched above. A monastic framework does not mean a cloistered life and total detachment from the surrounding world. We must not close ourselves off, but open ourselves, with missionary energy, toward everyone, well aware of the fact that that energy very often means encountering people who do not have faith, or even work against the Church.

In order to grow, the faith of an individual person needs to be given. We have something to

announce, to every person, in every place, and at every time. Of course it is risky “going out into the world,” but this risk is unavoidable. There will likely be many defeats and disappointments for those today who offer their company without renouncing their Christian identity, just as there are for those who have the courage to publicly propose the contents of the faith. But it indispensable to give oneself with that degree of freedom from the outcome and the detachment that is called virginity, unto the point of potential martyrdom. A faith that does not consider even that supreme sacrifice to be a possibility, as happened to Jesus, is not a mature faith.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.