A Tale Of Two Photos

If you read the New Yorker profile of me, you saw that this photo (by Maude Schuyler Clay) is the one they chose to illustrate it:

Maude Schuyler Clay is a terrific portraitist. You can see her other portraiture here — please do go see it, because it’s something else. Her 2015 collection Mississippi History is mesmerizing; Richard Ford wrote about it for the New Yorker here.

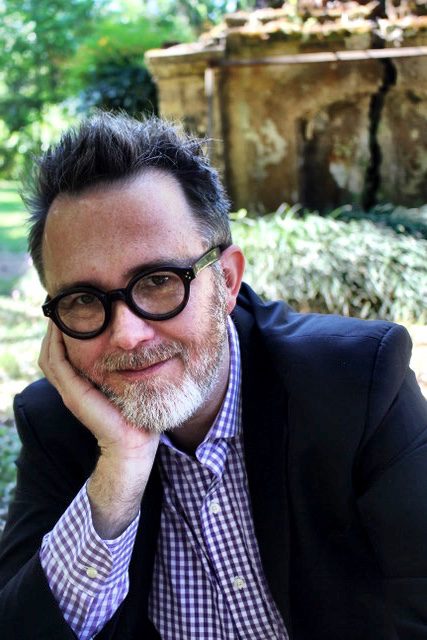

Yesterday, Maude e-mailed a different photo from that long Sunday afternoon session:

This is what I think I look like. This is what I feel like inside most of the time.

But the first photo — the one New Yorker photo editor Thea Traff chose — reveals a profound truth about me, a truth that Joshua Rothman’s profile also captures, I think. I have been thinking all week about it, to be honest. I think Maude’s more conventional portrait is magnificent, but I believe the unconventional one is arguably more truthful, or at least far more illustrative of the truth Josh Rothman tells in his piece, titled “The Seeker.” I think the juxtaposition of the two images tells us something important about art, truth-telling, and discovery. Let me explain.

Often I’ve remarked here on how strange it is for me to meet people in person, and have them tell me that I’m a lot more laid back than they expected, given the nature of my writing on this blog. Well, the photo in front of the cracked mausoleum is how I am in everyday life. That’s the me you meet — and my happiness there is not incidental to the broken tomb, insofar as it is symbolic of the Jesus Christ of whom we Orthodox sing at Pascha:

Christ is risen from the dead/trampling down death by death/and upon those in the tomb bestowing life.

That content man in front of the cracked tomb, that’s the me that I am most of the time. The photo without the glasses, though, is the me you meet on this blog, which is more reflective of my inner turmoil when I contemplate the kinds of things I generally write about here. Both are truthful portraits. The less conventional one, though, illustrates facets of the man relevant to Josh Rothman’s profile.

In The Moviegoer, Walker Percy wrote, “To become aware of the possibility of the search is to be onto something. Not to be onto something is to be in despair.” The first photo shows the man who has found what he’s looking for. The second photo is of the man who is aware that there is something more behind the veil.

I wrote last week about how all this surprised me with the recognition that my late father and I are a lot more alike than I ever imagined. We both were (are) deeply, deeply concerned with fundamental order, its waning, and our own impotence in the face of that fact. We just drew the lines in different places. From last week’s post:

Though my dad and I clashed intensely for much of our life together, what we shared was a profound need for order, to believe that the world was ordered in a certain way, and that people were seeking to harmonize with it. But people, being people, tend not to do this, hence the anxiety within the ordered person. My father worried a great deal because the world surrounding him would not order itself, or be ordered, as he thought it should. This anxiety took a painful toll on me, because my own disorder (in his eyes) was a thorn in his flesh. It was by no means the only one, but given that I was his only son, and was named after him, it was his chief torment. At least until his daughter, the Golden Girl who never did anything wrong, died of cancer at age 42.

What Josh Rothman’s profile, and Maude Schuyler Clay’s photo, revealed to me is how very much alike my late father and I are. There’s one big difference, though: Though we were (are) both restless souls, Daddy was convinced that he had found the right place; his restlessness manifested itself in countless projects around his land, by which he sought to order it. Mine was more inward, though certainly it had outward manifestations. Daddy never doubted himself or his way of living, and indeed could not have conceived of doing so. That’s not me, and never was. But the anxiety, that we share.

Over the past few days, I’ve been thinking even further about this, from our similarities and our differences. As I’ve said here often, my father was a Stoic, far more than he was a Christian. He didn’t perceive the difference, really, nor, as Percy understood, would many old-fashioned Southern men. Percy once wrote of a character in a Faulkner short story:

The nobility of Sartoris — and there were a great many Sartorises — was the nobility of the natural perfection of the Stoics, the stern inner summons to man’s full estate, to duty, to honor, to generosity toward his fellow men and above all to his inferiors — not because they were made in the image of God and were therefore lovable in themselves, but because to do them an injustice would be to defile the inner fortress which was oneself.

That was Daddy, though I would modify this to say that he didn’t think any man (including himself) was lovable in himself, but only lovable insofar as he did his duty. To avoid defiling the inner fortress which was oneself — that was what drove him, and what drove me for most of my adult life. The tension between the Christianity I affirmed with my mind and the Stoicism soaked into my bones defined my interior life until it all broke down, and I had to become a full Christian (see How Dante Can Save Your Life for that full story). There was a certain nobility in my father’s agonizing willingness to bear suffering — his own physical decline, and the emotional blows life landed on him. He thought that he could change the world by imposing his own formidable will on it, but when the world refused to be changed, he turned that will inward, toward the last-stand defense of his inner fortress.

So, when his Prodigal Son returned home, he did not understand it as a Christian would have done. He understood the event as a son who had refused to do his duty returning to his post. But when the son insisted on being unlike his father, the father absorbed it as another betrayal, one to be endured, not in any way redeemed. To have admitted error in any way would have been to defile his inner fortress. Had he been able to turn his fortress into a temple, things might have turned out better for us all. But he could not; none of them could. So it all came tumbling down.

As you know, he and I came to terms in the months before he died, and it was a beautiful, grace-filled ending, for which I will be forever grateful. Here’s the thing, though, that rests on my mind: Is the Benedict Option project little more than a grandiose attempt on my part to achieve the same doomed objective that my father did: defend a fortress that cannot be defended?

My father wanted to defend the family, a place, and a way of life. I want to defend the Christian faith, which is embedded in a way of life. What do the two projects have in common? How do they differ? Is it possible to learn from the failure of my father’s quest to make my own more achievable?

First, the things they have in common. Both of us understood — I have to use the past tense when talking about my dad — that changing times threatened what we valued most. Both of us esteemed tradition, family, and place. We also understood, however intuitively, that what we loved had to be concrete, not abstract. And we knew that self-discipline was important to achieving most good things.

How do they differ? This is where it gets interesting. My dad believed that he could impose his favored solution by bending everyone in his family to his will. He could not do this, not only because people have free will, but also because of other contingencies, e.g., the unexpected advent of terminal cancer into the life of his daughter, the Golden Girl, and her demise. I don’t believe that a vibrant Christian orthodoxy can be achieved by force of anybody’s will. The Church can only propose; it cannot impose.

And, Daddy believed that tradition, family, and place were ends in themselves. I don’t believe that tradition, family, place, or the Church are ends, but rather means to an end, which is unity with Jesus Christ, and all that entails.

What does my father’s project have to teach me about the Benedict Option?

For one, Dante taught me that all sin comes from disordered love: loving the wrong things, or loving the right things too little or too much. Family is good. Place is good. Tradition is good. But these things are only good insofar as they reveal and guide one to God. To place anything above God is to make it an idol — and our idols inevitably tyrannize us. So, if our goal in the Benedict Option is only to preserve the outward forms of the Church, or the Church as a way of life, we will fail. We must instead strive to preserve the outward forms of the Church for the sake of nurturing its inner life, and orienting it towards communion with God. Inside the Benedictine monastery, everything the monks do is not for its own sake, but to deepen their conversion.

For another, mercy is as important as justice. My dad was not a stern man, generally. The relaxed face of myself that you see? That’s also his face. Most of the time Daddy was happy. It is hard to overstate how much people loved him and respected him. He could be very funny, and quite tenderhearted. My mother once told me how frustrated she was with him during a time in which he owned some rental properties. Some renters took advantage of him because he had a soft spot for people who had fallen on hard times. He’d let people get backed up on their rent because he didn’t want to be cruel to them — even when he had reason to believe they were cheating him. And he would go out of his way to help people. There were very good reasons why he was so widely admired.

Yet it seems to me that he granted others mercies that he did not reserve for his own kind. He was Col. Sartoris the Stoic: he was a true gentleman towards others because that is what a gentleman does. He cut everybody else slack, but not his own family, because we ought to have known better. So many times as a child did I hear the chastisement, “We raised you better than that!” Maybe it’s not that way so much with Southern families today, but it is difficult to overstress the extent to which we were raised in a shame-honor culture. There is little flexibility within it. You either do your duty, or you fail to do so, and bear the shame of that. What I never could figure out is why all the success I enjoyed in the world as a writer and journalist meant nothing to him. I see it now: because I had failed to do my duty.

I revered my father for his strong moral sense, but in truth, it was a Stoic’s morality, not a Christian’s. Forgiveness wasn’t a big part of it. Nor was humility. If preventing the inner fortress from being defiled meant that he had to deny his own culpability, well, then that’s what he would do, by force of will.

Once, back in the 1990s, during my first failed attempt to re-enter his world, I showed him the Auden poem As I Walked Out One Evening. Especially these verses:

‘O look, look in the mirror,

O look in your distress:

Life remains a blessing

Although you cannot bless.‘O stand, stand at the window

As the tears scald and start;

You shall love your crooked neighbour

With your crooked heart.’

See, this is us! I tried to say. We’re all broken, but we can love each other.

He didn’t get it. Why would anyone love their crooked neighbor? He’s a crook! He ought to do right.

So, the Benedict Option. If it is to have any chance of working, it will have to know when to be disciplined, and when to be flexible. It will have to be willing to bear suffering, as my father was, but find a way to transform that suffering into redemptive love, which his Stoicism could not accomplish. And it will have to keep squarely before it the truth that this world is always passing, and we should hold perishable things lightly, so that we can hold imperishable things firmly. This is a paradox.

There are surely many other lessons to be learned. I welcome your thoughts on this. Every book I’ve written began as a series of blogs here, vastly enriched by the input of you readers. This next book of mine, whatever it is, will likely be no different.

I don’t know what my next book will be, or when I will start it. But the questions unearthed by The Benedict Option are staring down at me, and I can’t shake their gaze. Here’s what the art of photographer Maude Schuyler Clay and the craft of photo editor Thea Traff has done for me: they have shown me that some truths are better explored through art than philosophy — in my face, through fiction than non-fiction. The juxtaposition of the two photos at the top of this essay tells me more about myself than the last three books I’ve written. Maybe the way to find the answers I’m looking for now is to stop thinking about them, and instead create characters who try to live through the problems they pose. Rainer Maria Rilke wrote to Franz Kappus, the young poet:

“Be patient toward all that is unsolved in your heart and try to love the questions themselves, like locked rooms and like books that are now written in a very foreign tongue. Do not now seek the answers, which cannot be given you because you would not be able to live them. And the point is, to live everything. Live the questions now. Perhaps you will then gradually, without noticing it, live along some distant day into the answer.”

Live them … or live them through the characters you create, either in a novel or a screenplay. The anxious contemplative in the photo above will try that.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.