At the Tomb of Dante Alighieri

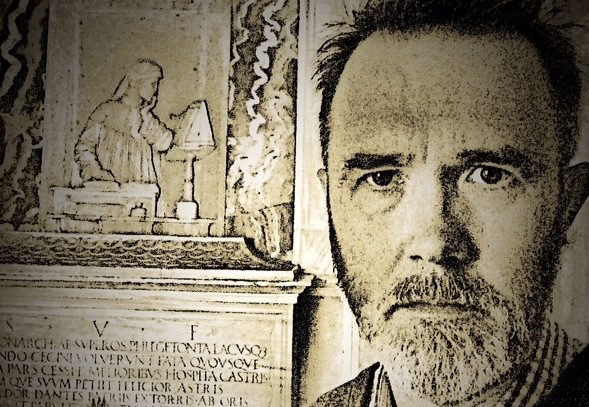

It has been difficult to write about what it was like to stand at the tomb of Dante, in Ravenna, and to think, and to pray. The tomb is a small 19th century marble mausoleum, the size of a tiny chapel, in fact. When I stood face to face with the grave of the great man, the man whose masterpiece meant so much to me, and helped save my life, I had to fight my standard reaction, which is to immediately try to get outside of myself and to analyze, to write.

I forced myself not to do that, and instead to put myself in his presence, and in the presence of God, and to be fully there. As a result, I can’t remember what was going through my mind in those first moments — and that is a good thing.

I do remember this: I thanked him from the bottom of my heart and from the center of my soul for what he had done for me. And I thanked God for the life of Dante Alighieri, as painful as it was for the exile, because he turned his own suffering to great good, and reached across the ocean and the centuries to rescue me, as he had been rescued (in his imagination) by Virgil.

How can I ever repay him? I asked his prayers that I would write well of him in this book I am undertaking.

After a while, I stood to the side of his grave, at the back of the sepulchre, took out my Portable Dante (Mark Musa, trans.) and read Canto 26 of Paradiso as a kind of prayer. This is Dante, in heaven and temporarily blinded, addressing St. John, telling the Gospel writer how he came to know of God’s love. Excerpt:

I said: “Through philosophic arguments

and through authority which comes from here

such love as this has stamped me with its seal;

for good perceived as good enkindles love,

and makes that love more bright the more that we

can comprehend the good which it contains.

So, toward that Essence where such goodness rests

that any goodness found outside of It

is only a reflection of its ray,

the mind of man, in love, is bound to move

more than toward any other, once it sees

the truth on which this loving proof is based.

Such truth is made plain to my mind by him

who demonstrates to me the primal love

of each and every endless entity.

Plain it was made by the True Author’s voice

when He said, speaking of Himself, to Moses:

‘I shall show you all of my goodness now.’

Made plain it also is from the first words

of your great Gospel which cries out to men,

loudest of all, the mysteries of Heaven.”

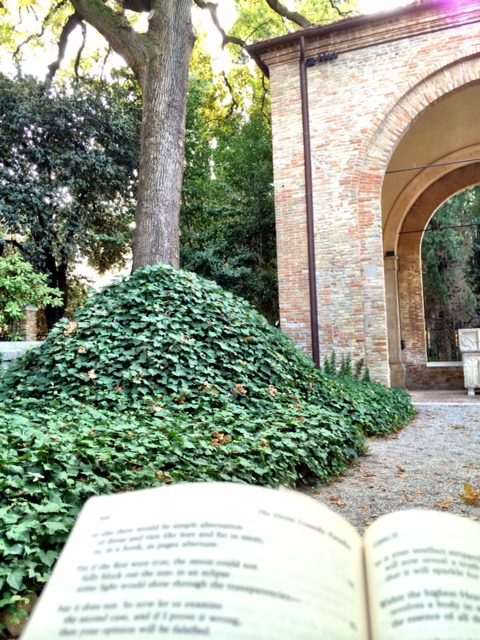

When I finished, I took a photo of that moment in that holy place, so I would never forget the vision:

I went into the garden next to his tomb, sat on the steps behind the sepulchre, and began reading Paradiso. I intended to read the entire poem, but sunset overtook me around Canto 12. Here is the view from my seat:

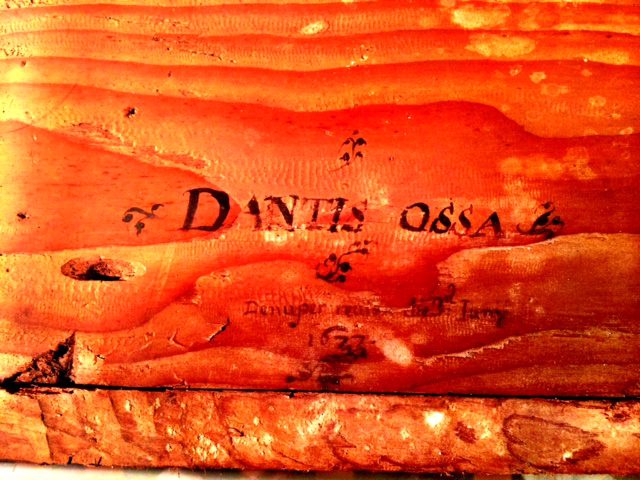

See that ivy-covered mound? That’s where Dante’s bones were hidden during World War II, to keep them from being stolen. On the other side of that mound is a brick wall that had been part of the old Franciscan monastery. I did not realize that Dante’s bones had been lost for centuries, hidden by the Franciscans, who, like everyone else in Ravenna, feared that Florence or its agents within the Vatican would seize the remains of the exiled poet. In 1865, this happened (the report is from a London newspaper):

Whilst some workmen were employed in clearing the chapel which contains DANTE’s monument from the outbuildings surrounding it, a peculiar noise in striking the outer wall suggested to them that some hollow might be found within. Accordingly, on using some violence on that portion of the wall where the hollow sound was produced, a wooden coffin was discovered, from which several bones fell out in the confusion of the first discovery. On a scroll within the coffin was found written, ‘Dantis ossa a me Frate Antonio Santi hic posita 1677, die 18 Octobris;’ and inside the lid of the coffin the following inscription was placed: ‘Dantis ossa denuper revisa 3 Junii, 1677.’ The coffin had been stowed away with its precious deposit within this mural sepulchre at that date, and he remained there till now. The Italian Deputy MONZANI, Col. MALENCHINI and ATTO VANNUCCI were in “DANTE’s chapel” at the moment of the interesting discovery. The Prefect and Mayor of Ravenna were forthwith called to the spot. The skeleton head and bones of DANTE were examined carefully in their presence. Save a fragment of the cranium, the whole of the lower jaw, and three joints of the right hand, which were missing, all the bones were found to be intact.

You can see the box in which the bones were discovered next door, in the Dante museum:

And you can also see a 2006 recreation by scientists, based on cranial measurements, of what they think Dante looked like:

It was all very strange, if you think about it: a middle-aged man from a small Louisiana town, making a pilgrimage to a grave in an Italian city on the Adriatic, to pay respects to a Tuscan poet of the High Middle Ages. Of all things! But I needed to do this, as an act of pietas. What had this wandering Tuscan saved me from? There’s a book in that, but in sum, he saved me from what the Welsh call hiraeth, defined as:

hiraeth: (n.) a homesickness for a home to which you cannot return, a home which maybe never was; the nostalgia, the yearning, the grief for the lost places of your past.

Here’s an article from the Paris Review about hiraeth. Excerpt:

So hiraeth is a protest. If it must be called homesickness, it’s a sickness come on—in Welsh ailments come onto you, as if hopping aboard ship—because home isn’t the place it should have been. It’s an unattainable longing for a place, a person, a figure, even a national history that may never have actually existed. To feel hiraeth is to feel a deep incompleteness and recognize it as familiar.

Dante, through his Commedia, helped me to understand that I could not go home again, that my own hiraeth was in fact a manifestation of something unfulfillable within me, and that my own deep sorrow and pain of exile emerged because I had taken a false path, having lost the straight one. It wasn’t that I had made a mistake in returning to my childhood home; I had not. It was that what I thought I was coming home to doesn’t exist, and never did. What I was looking for was God, in a way that I had never known Him. And Dante showed me that I had never known him because I loved, and was loved, in misguided ways. It was through prayer, and therapy, and most of all the Commedia that God toppled false idols, helped me change course, and made me whole again, or at least set me at last on the straight path. And that is when I began to get well.

Since that happened earlier this year (I tell the story in greater detail here), I have seen how Dante’s insights into human nature and the character of man could help so many of us with our particular struggles. That’s what my forthcoming book, How Dante Can Save Your Life, is about. Standing at Dante’s grave, I asked the master, “Please, help me to write well of you.” That great, great man gave me a priceless gift; the most I can give him in love and gratitude is to pass that gift on to others.

for good perceived as good enkindles love,

and makes that love more bright the more that we

can comprehend the good which it contains.

I began writing the Dante book yesterday. If you pray, please pray that I write well of Dante, who led me out of a dark wood and into the light, and who, I hope, will lead many, many more through my efforts.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.