Another Year Of Rod Dreher’s Diary

This month marks the one-year anniversary of Rod Dreher’s Diary going behind a paywall. RDD is my Substack newsletter — usually sent twice weekly, sometimes more, always with a long post. It differs from this blog in that it focuses exclusively on religion and sources of meaning, and is written not to lament and diagnose, but to find reasons for hope, and means of sustaining that hope. I also write more personally about religion there than I feel at liberty to do on this blog. That is to say, I try to avoid here anything that seems like proselytizing; in the newsletter, I don’t actively proselytize, but I am more free with my religious opinions there.

The cost of subscribing is five dollars per month, or fifty dollars for the year. The thing started out as The Daily Dreher, but I realized after several months of doing that that I was burning out, writing a thousand words or so daily, in addition to my blogging and other writing. Writing between one and three newsletters each week — two is the most common schedule — has been far more manageable.

To give you an idea of what the thing is like, here is almost the full text of the most recent Diary:

Someone, don’t know who, sent me a used book titled Powers of Darkness, Powers of Light, a 1991 book by the English journalist John Cornwell. Seeing Cornwell’s name piqued my attention. I recall that Cornwell is an ex-Catholic and ex-seminarian who published a highly controversial book years ago about Pius XII, with the slanderous title Hitler’s Pope. Normally I wouldn’t read a Cornwell book, but Powers details a simplified version of what I will be doing this year: traveling around looking at evidence for the miraculous, and inbreakings of the divine into our world. So I gave it a try.

The book, which I just finished, is disappointing in a way that it was destined to be, I suppose, though I’m very glad I read it because it’s an example of how this kind of book can go wrong. If credulity is one flawed approach to a project like this, then too much skepticism is another. The main lesson I took from the book is that unbelief is also an exercise in faith.

Cornwell doesn’t set out to be a debunker. His pilgrimage was inspired by a midlife curiosity about the faith that he had long ago rejected. There is, of course, nothing wrong and much right with approaching these things with skepticism. Yet you realize after a while that nothing is going to be able to breach the author’s tower of resistance, heavily fortified with English professional-class disbelief. Whenever Cornwell is faced with something he can’t explain, he always finds some rationalistic reason for it, or at least says that there is probably such an explanation. At other times he retreats in disgust at the vulgarity of the thing on display, as if God had offended him by showing Himself in such a trashy way.

I get that. It happened to me once. In January of 1998, my wife and I were on our honeymoon in Portugal, and made a side trip to Fatima to honor the Virgin Mary, and to thank her for her role in bringing us together. I had never been to a popular pilgrimage site, and had no idea what to expect. A bus from Lisbon dropped us on the outskirts of the village, a 90-minute drive north of the Portuguese capital. It was a cold, grey day. Julie and I tramped towards the cluster of buildings that indicated village life. But nobody was there. We had arrived in the depths of the off-season.

It was, we reckoned, the main street of Fatima. It was appalling. Religious tchotchke shops everywhere. One had glow in the dark plastic statues of the Madonna, in several sizes, filling a window. There was Fatiburger, and the John Paul II Snack Bar. This town lived off of religious tourism. It was gross. We checked into our hotel — I think we were the only guests — and then made our way towards the end of the street, to the vast plaza in front of the basilica.

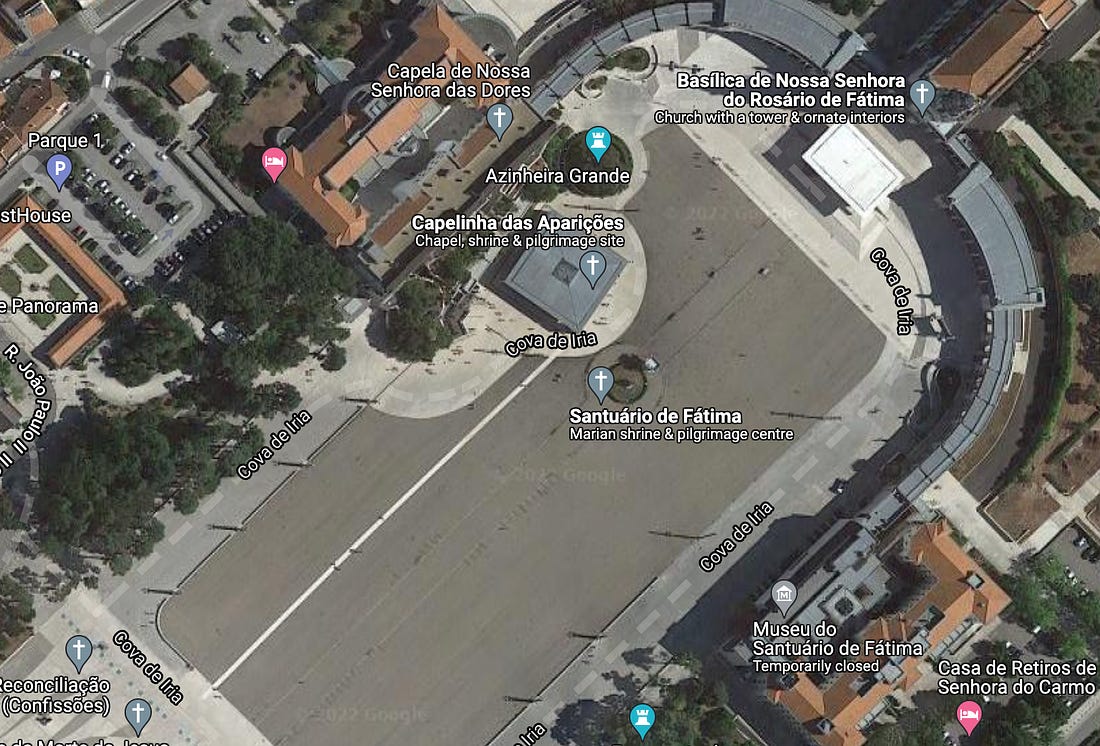

There we saw a mass of pilgrims streaming into the church; it was January 8, a Marian feast day. It really did look like James Joyce’s oft-quoted line about the Catholic Church: “Here comes everybody.” As we stood at the edge of the crowd watching, a family approached from the right. There was a young Portuguese mother moving forward on her knees, with maybe a quarter-mile ahead of her. Here’s a photo from Google Earth of the plaza. Julie and I were standing towards the bottom left of this photo, on the north side of the white line, between the line and the trees. You can see how far that mom had to do on her knees to reach the basilica (upper right). She was doing this, mind you, in a cold drizzle, with the plaza asphalt damp under her knees.

Standing behind her was her husband, holding a baby, and an older woman — either her mother, or her mother in law. They were moving forward to thank God and the Virgin for the baby. The mom did not care about the hardship of “walking” on her knees, nor did she care what people might have thought of her. Such faith!

As I stood there marveling, I realized that judging by the modest dress of this family, they were probably the sort who would fill up the trunk of their car with tacky religious tchotchkes before heading home. And yet, upon whose heart — mine or theirs? — would the Lord look more favorably? To ask the question is to answer it. I repented.

This is not to say that standards of beauty are irrelevant. But it is to say that they should be considered in context. There is nothing more beautiful in the sight of the Lord than the gratitude and humility of that Portuguese family.

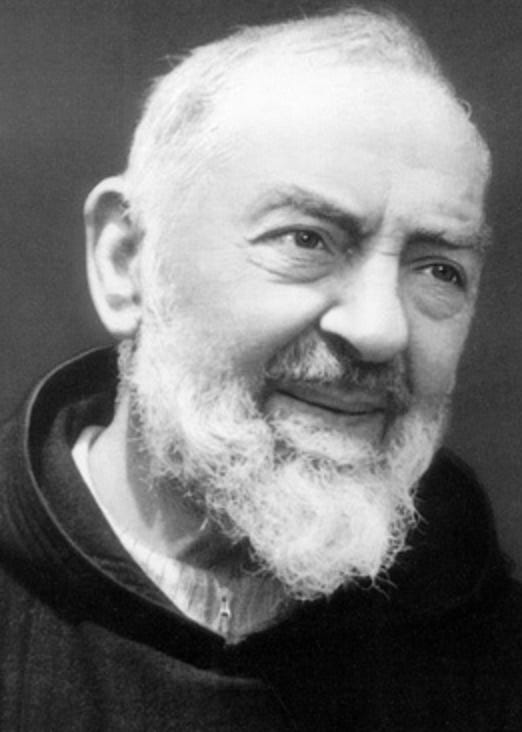

Anyway, back to Cornwell. He opens his book with an arresting anecdote based on an interview he did with the Catholic novelist Graham Greene. Cornwell visited him a year or so before his death in 1991. Cornwell questioned him on the nature of his Catholic faith, and found that Greene didn’t believe in much: not in heaven, not in hell, not in the devil, not in angels, and so forth. So why did he still call himself a Catholic? Because, Greene said, that he also doubts his disbelief. Then he told a story about Padre Pio, the great Franciscan mystic and stigmatist, who died in 1968.

“I am able to doubt my disbelief because I once had a very slight mystical experience. In 1949 I travelled out to Italy to see a famous mystic known as Padre Pio. He lived in a remote monastery in the Gargano Peninsula at a place called San Giovanni Rotondo. He had the stigmata, displaying the wounds of Christ in his hands, feet and side. At this time my belief in God had been on the ebb; I think I was losing my faith. I went out of curiosity. I was wondering whether this man, whom I had head so much of, would impress me. I stopped in Rome on the way and a monsignor form the Vatican came to have a drink with me. “Oh!” he said, “that holy fraud! You’re wasting your time. He’s bogus.”’ Greene looked up at me challengingly.

“But Padre Pio had been examined by doctors of every faith and no faith,” he went on. ‘He’d been examined by Jewish, Protestant, Catholic and atheist specialists, and baffled them all. He had these wounds on his hands and feet, the size of twenty-pence pieces, and because he was not allowed to wear gloves saying Mass he pulled his sleeves down to try and hid them. He’d got a very nice, peasant-like face, a little bit on the heavy side. I was warned that his was a very long Mass; so I sent with my woman friend of that period to the Mass at 5:30 in the morning. He said it in Latin, and I thought that thirty-five minutes had passed. Then when I got outside the church I looked at my watch and it had been two hours.”

Greene stopped for a moment as if to gauge my reaction.

“I couldn’t work out where the lost time had gone,” he went on. “And this is where I came to a small faith in a mystery. Because that did seem an extraordinary thing.”

He sat for a while in reverie. Then he took a well-worn wallet from his trouser pocket and fished out two small photographs. They were sepia, dog-eared. As he handed them over I detected a faint air of self-consciousness; as if, English gentleman that he was, he had been caught out in a gesture of Latin superstition. One depicted Padre Pio in his habit, smiling. The other showed the monk gazing adoringly at the host during Mass. The possession of the pictures, the gesture of sharing them, seemed a declaration of loyalty to faith.

“Why do you keep them in your wallet like that?” I asked.

“I don’t know why I put them in my pocket,” he said. He looked a trifle haunted. “I just put them in, and I’ve never taken them out.”

I decided to press him a little further. “If you hadn’t had your mysterious experience with Padre Pio might you possibly have lost your faith?”

“I don’t think my belief is very strong; but, yes, perhaps I would have lost it altogether…”

“So what, in the final analysis,” I said, “does religion mean to you?”

Greene looked at me directly, wonderingly. He seemed at that moment ageless; there was an impression about him of extraordinary tolerance, ripeness.

“I think … It’s a mystery,” he said slowly and with some feeling. “There is a mystery. There is something inexplicable in life. And it’s important because people are not going to believe in all the explanations given by science or even the Churches … It’s a mystery which can’t be destroyed…”

Greene’s dependence on that tiny sliver of belief brought to mind the case of Manfred, from Canto III of Dante’s Purgatorio. Manfred was an actual historical figure, a royal who died in battle, excommunicated from the Catholic Church. But he made it into Purgatory (which meant that he would eventually be with God in Paradise) because as he fell off his horse, mortally wounded, he repented.

As I lay there, my body torn by these

two mortal wounds, weeping, I gave my soul

to Him Who grants forgiveness willingly.

Horrible was the nature of my sins,

but boundless mercy stretches out its arms

to any man who comes in search of it…

…

The church’s curse is not the final word,

for Everlasting Love may still return,

if hope reveals the slightest hint of green.

For God so loves the world that He will accept the slenderest repentance — as think as the first green shoot of the spring — and draw us to Himself.

There is another story in the book, a written account by the novelist Tobias Wolff, a friend of Cornwell’s. Wolff tells the story about going to Lourdes in 1972, as a young man, wanting to volunteer to help the sick coming to take the waters. He explains that he has always had very poor vision, but hated wearing glasses, so he wandered through his youth in a blur.

Wolff spent some of his time on a crew of young men who stood in the grotto’s waters, lifting the sick out of their chairs and beds and immersing them in the bath. He saw the human body in all manner of agony. One day, his crew accompanied a group of disabled Italian pilgrims to the airport to catch their chartered flight home. Wolff’s assignment was to care for a completely paralyzed two-year-old girl, confined to her bed with tubes coming out of her nostrils, draining into bags under her blanket. It was hot and muggy as they loaded the plane, but then, for no apparent reason, the door to the plane closed, stranding the helpless child.

Wolff began to panic. The plane wasn’t moving, so he hoped that the door would eventually re-open. In the meantime, he did his best to keep the child cool. Flies discovered her face, and no matter how hard Wolff worked to keep them off of her, the insects harassed the toddler. Wolff says that he “became desperate with anger,” an anger that he realized was disproportionate to the situation. He was raging at the injustice of it all, at the cruelty of the world. When the plane door re-opened to let the child on, Wolff says he was sobbing, but as everybody was sweating buckets, nobody could tell.

On the bus ride back to Lourdes from the airport, Wolff, still not wearing his glasses, noticed that he could see things in the distance. He rubbed his eyes to clear them, thinking that maybe the mixture of sweat and tears had formed a kind of lens over his eyes that enabled him to see. But the effect didn’t go away.

I felt giddy and restless, happy but uncomfortable, not myself at all. Then I had the distinct thought that when we got back to Lourdes I should to to the grotto and pray. That was all. Go to the grotto and pray.

But he didn’t do that. The bus dropped him off at the barracks, where he fell into conversation with a gregarious Irishman he had befriended. Wolff didn’t tell him about the miracle, and was aware that he was hiding this from his Irish friend, who would have been interested, not judgmental. Wolff was aware this entire time that he was not going to the grotto to pray as he had been told to do. Eventually the two went to dinner, and Wolff never made it to the grotto that day. The next morning, his eyes were back to their broken state, and he had to wear glasses again.

Wolff tells Cornwell:

What interests me now is why I didn’t go. I felt, to be sure, some incredulity. But this wasn’t the reason. I have a weakness for good company, good talk, but that wasn’t it either. That was only a convenient distraction. At heart, I must not have wanted this thing to happen. I don’t know why, bu tI have suspicions. I suspect that I considered myself unworthy of such a gift. And if I had secured it, what then? I would have had to give up those doubts by which I defined myself, in the world’s terms, as a free man. By giving up doubt, I would have lost that measure of pure self-interest to which I felt myself entitled by doubt. Doubt was my connection to the world, to the faithless self in whom I took refuge when faith got hard. Imagine the responsibility of losing it. What then? No wonder I was afraid of this gift, afraid of seeing so well.

Incredible, isn’t it? Whoever among you sent me this Cornwell book, you have my thanks, because this Wolff anecdote is going into my book. That story illustrates one of the fundamental messages of the book: that we tell ourselves that we would believe if only we could see evidence for God’s existence, but in fact we prefer our blindness, because it gives us license to behave in ways we could not do if we were sure that God was real and watching over us. I have been there. Wolff was 27 years old when this happened — two years older than I was at my conversion. I spent my late teen years and the first half of my twenties telling myself that I would believe if only I had proof, but deceiving myself for the same reason that young Wolff did: because the “freedom” that I thought I deserved depended on nurturing my doubts. When you are at a party, and you have had a lot to drink, and you would like to go home with a cute girl you’ve been talking to all night, it’s amazing how vividly one’s religious doubts show themselves.

This is Cornwell’s problem in the book. Well, not necessarily the sexual aspect of it, but he clearly has so much invested in his worldview as a skeptic that by the end of the journey he chronicles here, I both pitied him and was quite annoyed by him. Annoyed, because it was clear that nothing he saw or heard would change him, because he did not want to be changed. Pitied, because he was plainly unhappy with his faithlessness, which is why he undertook the journey in the first place. It was clear to me by the time I finished Cornwell’s account that he was too afraid of the responsibilities that would come with losing his doubt.

In my book, I will be addressing this head on. I plan to visit Rocamadour, a medieval pilgrimage site in France. It is where the spiritual climax of Houellebecq’s novel Submission occurs. The dissolute protagonist François goes on pilgrimage there in a half-hearted attempt to regain his lost Catholic faith. In one of the worship services, François has a semi-mystical experience, and is at the very door of conversion … and then decides that he’s just hungry, and suffering from “an attack of mystical hypoglycemia.”

Everybody wants to get to heaven, but nobody wants to die. There is no telling how many people would have been saved, and could yet be saved, if they were not afraid of repentance, and did not care what other people would think of them.

This year I will be traveling a lot to holy places, researching my forthcoming book about Christian re-enchantment. I will share most of my field notes with my newsletter subscribers. If you would like to subscribe, click here for instructions.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.