A Theology Of Rock

A theologian friend posed some great questions in an e-mail the other day, one that a couple of readers raised in a comments thread. It has to do with God and rock music. From his e-mail:

What is your theology of engagement with rock and rock culture? …

I think you’d a great person to write about this for two complementary reasons.

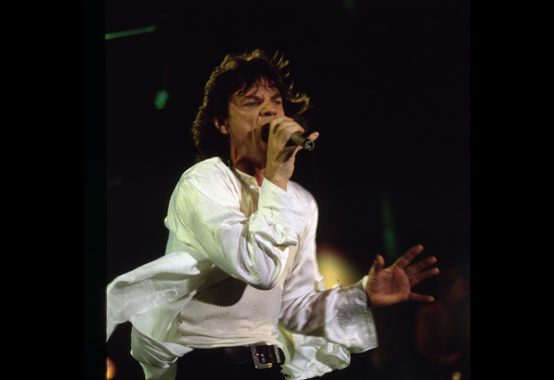

1) You take seriously the potentially corrosive effects of popular culture on our imaginations. You understand the significance of certain classical asceticism for deepening in prayer. You take things like fasting, cultivating silence, and traditional sexual ethics seriously. You entertain degrees of simply saying “no, thank you” to popular culture when you consider the Benedict Option. If a boy at West Feliciana High School writes love poetry to Nora someday like Mick Jagger speaks to women in his songs, you’d be appalled. I bet you read the Allan Bloom chapter on rock in “Closing of the American Mind” – he was a stick in the mud but he also wasn’t stupid – that you drive Matthew to Baton Rouge to read Homer suggests you take formation in the classics seriously.

2) And you have a robust theology of creation and enjoy all that is good. You like a good time, a good story and a good riff. It’s not a far cry from the sacramentality of a good VFT to a good Lou Reed or Stones song. You are a man of your/my/our generation, and we have many of the same songs on our internal sound track – it is what we are. We saw “Piranha in 3-d” together and had a laugh.

In light of the above, how do we narrate a theology of rock? On what terms – with what sort of prayerful engagement to guys like us engage with this music? When you expose Matthew to both the Divine Liturgy and the Clash, how would you describe what you’re up to?

I have been thinking about this since my friend wrote, but I confess I still haven’t come up with a stance that I find satisfying, morally or intellectually. But maybe if I set down some of the thoughts that went through my head as I pondered these excellent questions, we can have a good discussion about them. If you are not a religious person, these questions still apply to you. For example, no serious feminist can listen to most hip-hop, much less the Rolling Stones, without confronting cognitive dissonance. The basic question my theologian friend asks — and again, this is not strictly a theological question — is how we should properly react when the Devil (so to speak) has the best tunes? Here are my notes toward an answer:

1. In a sense — a limited sense — art is its own justification. Art that is morally (or politically, or theologically, etc.) correct fails if it lacks aesthetic quality. It don’t mean a thing if it ain’t got that swing. Artistic giftedness — that is, the ability to create music, writing, or visual art that has that “swing” often has nothing to do with the moral qualities of the artist. Caravaggio was a moral wreck. When it comes to rock, if it sounds good, it is good, aesthetically speaking.

2. But morality cannot be excluded from the issue entirely. The example to which I always return is Leni Riefenstahl’s “Triumph Of The Will,” her documentary of the 1934 Nazi Party rally at Nuremberg. It is a work of astonishing aesthetic power, deployed in the service of absolute evil. A rabbi screened it once when I was in college, because he thought — correctly — that it’s important for us to understand how the Nazis won over the German people. It was, in large part, through a mastery of aesthetics. Just as aesthetic excellence cannot be excluded from an evaluation of art, neither can morality. If you believe beauty is its own justification, how can you condemn Riefenstahl’s beautiful work in the service of evil? On the other hand, to call an artwork ugly because of its repugnant moral content requires us to deny the testimony of our eyes and ears, and just won’t work.

3. The question, therefore, is: how to weigh these things in the balance?

4. We have to consider what the purpose of art is. Is art meant to express thoughts, emotions, and modes of being? Or is art supposed to reflect ideals, and to harmonize with them? The answer, I think, is that both are legitimate functions of art. We seek both things in our art: representation and idealization — or, to put it in another way, the Real (the way thing are) and the True (the way things should be).

5. So, when I listen to the Rolling Stones sing in “Sister Morphine” about the desperate haze of drug addiction, I don’t take it as a recommendation to inject morphine, or to introduce myself to “sweet cousin cocaine,” but rather as a darkly potent representation of the power of drug addiction to consume a life — something that Keith Richards knew about. Similarly with the Velvet Underground’s “Heroin.” Neither are moralizing songs; they just describe the experience, and draw a kind of beauty from the bleakness. I can’t imagine listening to either song and wanting to partake of the experiences they represent.

6. To stick with the Stones, the narrator in “Under My Thumb” is a sexist pig who celebrates his piggishness towards women — specifically, in his domination of a pushy woman. This is part of the Stones’ bad-boy shtick. It’s a great rock song, but really, should we be taking pleasure in a narrator singing about his woman as a “squirming dog”? It ought to make us squeamish. Yet as Camille Paglia once said:

So by the time the women’s movement broke forth in 1969, it was practically impossible for me to be reconciled with my “sisters.” And there were, like, screaming fights. The big one was about the Rolling Stones. This was where I realized–this was 1969–boy, I was bounced, fast, right out of the movement. And I had this huge argument. Because I said you cannot apply a political agenda to art. When it comes to art, we have to make other distinctions. We had this huge fight about the song “Under My Thumb.” I said it was a great song, not only a great song but I said it was a work of art. And these feminists of the New Haven Women’s Liberation Rock Band went into a rage, surrounded me, practically spat in my face, literally my back was to the wall. They’re screaming in my face, “Art? Art? Nothing that demeans women can be art!” There it is. There it is! Right from the start. The fascism of the contemporary women’s movement.

OK, “fascism” is typical Paglian overstatement, but she’s right: this is subjecting art to a strict moral agenda that is inappropriate to the nature of art itself. Why is “Under My Thumb,” as offensive as the lyrics are to many, a great song, and maybe even a work of art? Because, in my view, it expresses with feral seductiveness the mindset of a misogynist. The lyrics themselves are repugnant, but set to that particular music, the ideas take on life. You are able to feel what the narrator expresses. The “truth” of his experience has become incarnated in words, rhythm, and melody, and has been communicated with unusual power because of the rhythm and melody. You may find the moral sentiment hateful, and I wouldn’t disagree with you, but you would be lying to yourself to deny the aesthetic power of that song.

7. The danger here is that you might also come to sympathize with the sentiment, seduced by aesthetics, and thereby be corrupted. There is no way around this risk, not with real art. It is also possible that genuine art that embodies and communicates the Good could “corrupt” a soul, and lead them toward goodness and light. That’s what the art of the Chartres cathedral did for me. So, when I consider what my “theology” of engaging with rock music might be, or ought to be, I consider that to encounter true art always involves the possibility of conversion, one way or another.

8. I find much hip-hop music to be aesthetically ugly and morally revolting. But if it were aesthetically pleasing to me, would I find the brutality, the greed, the misogyny and the macho posturing easier to take? Probably so. What is the difference between my finding some way to abstract, or to ironically distance myself from, the offensive lyrical content in rock songs I like, but in those songs whose rhythm and melody I do not like, I take the lyrics concretely? Is this not hypocrisy? Maybe. And yet, I cannot imagine a musical setting that would make the crude animality of, say, Jay-Z’s “Big Pimpin'” — which is by not remotely the worst of the genre. This stuff is pornographic.

But more pornographic than the Stones line, “You, you, you make a dead man come”?

9. W.H. Auden’s poem “Atlantis” is helpful in providing a framework for thinking through this problem. It’s a poem about the quest for paradise:

Atlantis

Being set on the idea

Of getting to Atlantis,

You have discovered of course

Only the Ship of Fools is

Making the voyage this year,

As gales of abnormal force

Are predicted, and that you

Must therefore be ready to

Behave absurdly enough

To pass for one of The Boys,

At least appearing to love

Hard liquor, horseplay and noise.Should storms, as may well happen,

Drive you to anchor a week

In some old harbour-city

Of Ionia, then speak

With her witty scholars, men

Who have proved there cannot be

Such a place as Atlantis:

Learn their logic, but notice

How its subtlety betrays

Their enormous simple grief;

Thus they shall teach you the ways

To doubt that you may believe.If, later, you run aground

Among the headlands of Thrace,

Where with torches all night long

A naked barbaric race

Leaps frenziedly to the sound

Of conch and dissonant gong:

On that stony savage shore

Strip off your clothes and dance, for

Unless you are capable

Of forgetting completely

About Atlantis, you will

Never finish your journey.Again, should you come to gay

Carthage or Corinth, take part

In their endless gaiety;

And if in some bar a tart,

As she strokes your hair, should say

“This is Atlantis, dearie,”

Listen with attentiveness

To her life-story: unless

You become acquainted now

With each refuge that tries to

Counterfeit Atlantis, how

Will you recognise the true?Assuming you beach at last

Near Atlantis, and begin

That terrible trek inland

Through squalid woods and frozen

Thundras where all are soon lost;

If, forsaken then, you stand,

Dismissal everywhere,

Stone and now, silence and air,

O remember the great dead

And honour the fate you are,

Travelling and tormented,

Dialectic and bizarre.Stagger onward rejoicing;

And even then if, perhaps

Having actually got

To the last col, you collapse

With all Atlantis shining

Below you yet you cannot

Descend, you should still be proud

Even to have been allowed

Just to peep at Atlantis

In a poetic vision:

Give thanks and lie down in peace,

Having seen your salvation.All the little household gods

Have started crying, but say

Good-bye now, and put to sea.

Farewell, my dear, farewell: may

Hermes, master of the roads,

And the four dwarf Kabiri,

Protect and serve you always;

And may the Ancient of Days

Provide for all you must do

His invisible guidance,

Lifting up, dear, upon you

The light of His countenance.

This poem poses the distinction between the Real and the True, and how difficult it is to distinguish between them — and indeed, how discovering the True in some real sense depends on encountering the Real. The prostitute who says she has found Atlantis is lying to you, and perhaps to herself, but (says the poet) if you do not understand why some people create counterfeit paradises for themselves, how will you know the the genuine paradise when you find it? In other words, if people find safe harbor in lies they tell themselves, and you do not have any knowledge of the contours of those counterfeit harbors, how will you know when you’ve found the real thing?

The stanza about dancing on the beach all night with that “stony savage race” is exactly the experience of rock and roll, don’t you think? The other night I was here at the house by myself, and feeling burdened by anxiety over this and that thing. When I find my worries overwhelming, I cook, and I listen to loud rock music. I put on the Black Crowes’ “Remedy,” and fired up the burners. The music, even more than the cooking, turns off my thinking like nothing else. Bach is sublime, but when I need the release of forgetting, only rock will do. Not even prayer, at its heights, can cause me to lay all my cares aside like a great rock song — precisely because it doesn’t try to be cerebral. Rock is about instinct. At its best, it offers transcendence in being liberated from the cerebral, and giving oneself over to the instinctive.

Isn’t this a counterfeit liberation, though? Counterfeit in the sense that it isn’t wholly real; it achieves the fulfillment of one part of our nature — the body — through the temporary denial of another part, the mind (or, if you like, the soul). For the Christian, this can only be a counterfeit transcendence, which is not to say that it is wrong, necessarily, but only that we shouldn’t mistake it for the real thing. To truly transcend is to have the body and the mind united, and united to God. To be caught up in the rapture of rock chords is blissful; nobody can deny that. God knows I wouldn’t. But it’s not Atlantis, and that’s the thing always to keep before us.

10. None of this satisfactorily answers the question about how a Christian listens to and affirms rock music that conveys a lyrical message that is immoral. At what point does the Christian draw a line saying, “I don’t care how great this music is, I cannot open myself to this”? I want to find bright, clear lines, but I can’t — and I hate the habit many of us Christians have of baptizing the secular things we like by inventing strained theological justifications for them. I end this digression almost as conflicted and as confused, and as “dialectic and bizarre,” as I started. The one thing my theologian friend’s question helped me to learn, by sending me back to Auden, is that the answer, or answers, will likely emerge out of a reflection on the distinction between what is Real and what is True, and how the two relate dialectically in art, including the art of rock music.

Your thoughts are welcome. I would be grateful if you could help me, and others, think through these things more clearly.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.