A Smaller, Purer Catholic University?

In 1969, the future Pope Benedict XVI predicted that the Catholic Church would suffer a purification in the years ahead, that it would lose a lot of its power, and many of its people — but that from that would emerge a smaller church composed of true believers. From this, the renewal will come.

I think of this prophetic statement a lot. I hadn’t really thought about it in terms of Catholic universities, until a friend e-mailed this Chronicle of Higher Education piece inquiring into whether or not the Catholic University of America is hurting itself by emphasizing Catholic distinctives. The piece is behind a subscriber paywall, but I can quote bits and pieces here.

Here is the gist of the problem:

A cost-cutting proposal at Catholic University of America, where administrators are seeking to close a $3.5-million operational deficit through layoffs and buyouts of 35 faculty members, has divided the campus and provoked a broader discussion about whether the institution has overplayed its religiosity to the detriment of student recruitment.

It is self-evident that Catholic University, a 131-year old institution founded by American bishops and considered the national university of the Roman Catholic Church in the United States, is inextricably linked to Catholicism. But at a time when many students of traditional college age have eschewed organized religion and come to question the church’s social teachings, Catholic University finds itself in an intensifying dialogue that pits the university’s core identity against market imperatives.

This is not a new debate for Catholic or for religiously affiliated institutions in general. Such colleges have long wrestled with how best to preserve their deepest values while still attracting students who want a vibrant social life and a collegiate experience that is more spiritual than it is strictly religious.

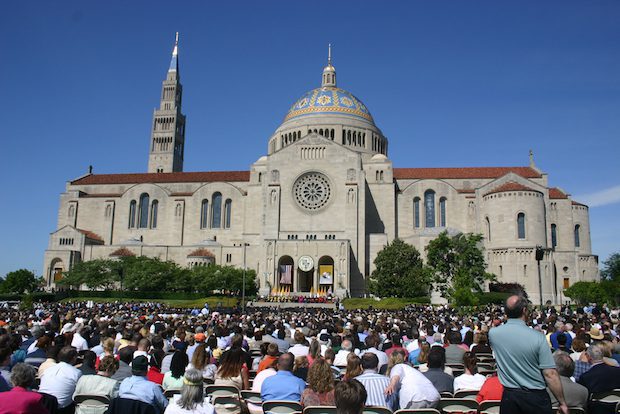

Yet, Catholic University, based in Washington, D.C., is at a particularly critical moment.

The visceral threat of faculty job losses has invited emotional exchanges about whether the bishops’ university — whose leaders have waded into today’s culture wars and tried to discourage college kids from having sex — has scared off some of the very prospective students that it needs most. Changes at the university, which in recent years has done away with co-ed dorms and promoted itself as a cultivator of “Catholic minds,” are now being scrutinized by campus critics as the unforced errors of an administration in need of a course correction.

CUA brought in consultants to help them figure out the situation:

In January, Catholic University professors huddled in Great Room B of the Edward J. Pryzbyla University Center, the same building where, a decade earlier, Pope Benedict XVI told an audience of Roman Catholic educators that they had a “particular responsibility” to “evoke among the young the desire for the act of faith.”

On the stage that day in January 2018 were guests of less renown, but their message got the professors’ attention. After a year of research, Art & Science Group LLC had concluded that prospective students do not see Catholic University as a top choice, that they are confused about its pricing, and — even among practicing Catholics — they are unlikely to respond favorably to additional faith-based marketing.

Prospective students, the consultants said in a videotaped presentation, perceive religion as a more-integral part of the student experience at Catholic University than at its peers.

“Unfortunately, that doesn’t help you,” said Eric Collum, a senior associate at Art & Science. “In fact, to the extent that they see you as being a religious place, it actually hurts you.”

“Students are open to having their experience enriched by Catholicism, but not necessarily defined by Catholicism,” Collum later added. “They want to go to college; they don’t want to go to church necessarily.” [Emphasis mine — RD]

And:

Abela and others chalk up most of the university’s challenges to demographic shifts. Roman Catholic high schools, the most reliable pipeline for Catholic University students, are graduating fewer and fewer people. [Emphasis mine — RD] This fall, more than half of private colleges, religious or not, missed enrollment targets, a Chronicle survey found.

In other words, factors beyond religiosity are no doubt in play.

“To lay it all at the feet of Catholic identity seems a narrow interpretation,” said Christopher P. Lydon, the university’s vice president for enrollment management and marketing.

In its analysis, Art & Science stressed the need for Catholic to emphasize its existing research opportunities for undergraduates, to guarantee on-campus housing, and to not skimp on “athletics and fun.” At the same time, Lydon says, the consultants found that “we had no more market share to gain through Catholic identity alone.”

“It’s not about the relegation of Catholic identity. It’s about the elevation of the academic student experience.”

I’ll stop there.

It would be a pity — actually, a tragedy — if CUA watered down its Catholic identity. There are scores of Catholic colleges where Catholics can get a Catholic-in-name-only education. It’s hard to see what the advantage accrue to CUA if it becomes one of the crowd.

On the other hand, holding on to its identity will probably cost it here in post-Christian America. Conservative Catholics — and conservative Christians in general — don’t like to think about this. We have told ourselves for a long time that standing firm in orthodoxy will rally those who are looking for institutions with confidence, as opposed to those led by uncertain trumpeters. But what if this is no longer true?

It shouldn’t surprise us. The studies of younger generations of Catholic Americans show that they are only nominally Catholic. For example, this takeaway from sociologist Christian Smith’s book about young Catholic Americans. Excerpt:

4. Catholic schools and parishes appear to have little effect. Smith spends some time on parishes and Catholic primary and secondary schools. On the surface, emerging adults who went to church and attended Catholic schools knew more about the faith and were more likely to practice it. Yet, these differences seem to be more associated with the parents’ faith than the parish or school itself. In other words, it is the parents and their religious commitment behind their children going to church, attending Catholic schools, and continuing to believe. The most significant factor for these institutions that Smith found was that Catholic schools prevented young adults from totally abandoning their faith.

5. Emerging adults need more than religious parents. If schools and parishes are less significant than parental commitment, is it all up to the parents? Supportive parents are one of the three most important factors affecting the faith of emerging adults, but Smith insists there are two more. Emerging adults must also regularly engage in religious behaviors and practices, and emerging adults must internalize the beliefs and make them their own. While parents are practically necessary, they are not sufficient on their own. Emerging adults need to choose the faith and practice it themselves.

(You see why The Benedict Option emerged in large part out of my reading Christian Smith’s work.)

What does this have to do with CUA? There are many fewer serious young Catholics in the US because there are many fewer serious older Catholics in the US. Smith found that most “emerging adults” — a demographic that includes older teenagers — think of their Catholicism in connection with their family heritage, but that’s about it. Parish life and Catholic school life doesn’t really change that. From the perspective of CUA, the formation of Catholic students who want what CUA has to offer is in serious decline. Thus, its enrollment.

Let’s assume that CUA changed its stance and direction. It might be easy enough to do. Pope Francis has given the school the cover it needs to liberalize: they could call it fidelity to the Holy Father’s “paradigm shift”. What then? I suppose theoretically it could see a rise in applications from nominal Catholics who would be interested in the Washington experience, but can’t afford or can’t get into Georgetown. CUA would become less attractive to students going to college with serious Catholic commitments, but then again, there aren’t a lot of choices for them anyway, so the losses at first might be relatively small.

But over time? Being just one more fallen-away Catholic college among many would pressure CUA constantly to be reinventing itself — no doubt further distancing itself from magisterial Catholicism.

If, however, CUA’s leadership sticks to its current vision, it also seems clear that the university will shrink. This is the cost of being faithful in post-Christian America.

It comes down to a question of vision. Again, conservative Christians like me have long been quick to jeer at liberal churches for casting off dogmas and doctrines that conflict with being a politically correct liberal. We snort when they fail to turn around their institutional decline in terms of numbers.

But what if we are in the same boat? What if those institutions are pursuing a vision that is unpopular, but one its leaders believe to be true? Aren’t we doing the same thing? We can (and should!) point out that the difference is that ours is based in Scripture and Tradition, whereas theirs is built around conforming to the Zeitgeist. But from the point of view of living out ideals, even when it costs you, we are more or less in the same boat.

The common problem is that Americans broadly just aren’t that interested in serious approaches to religion. Leaders of American churches and religious schools and colleges are going to have to face the question of what cost they are willing to pay to be faithful.

Philadelphia Archbishop Charles Chaput today publishes a beautiful, deep letter he received from a young Catholic man, a husband and father, urging the Catholic bishops to be uphold the truths they’ve been given to teach and to defend. The young man wrote, of the situation in the Catholic Church today:

This shift away from clarity is demoralizing for young faithful Catholics, particularly those with a heart for the New Evangelization and my friends raising children against an ever-stronger cultural tide. Peers of mine who are converts or reverts have specifically cited teachings like Humanae Vitae, Familiaris Consortio, and Veritatis Splendor as beacons that set the Church and her wisdom apart from the world and other faiths. Now they’re hearing from some in the highest levels of the Church that these liberating teachings are unrealistic ideals, and that “conscience” should be the arbiter of truth.

Young Catholics crave the beauty that guided and inspired previous generations for nearly two millennia. Many of my generation received their upbringing surrounded by bland, ugly, and often downright counter-mystical modern church architecture, hidden tabernacles, and banal modern liturgical music more suitable to failed off-Broadway theater. The disastrous effect that Beige Catholicism (as Bishop Robert Barron aptly describes it) has had on my generation can’t be overstated. In a world of soulless modern vulgarity, we’re frustrated by the iconoclasm of the past 60 years.

As young Father Joseph Ratzinger predicted nearly 50 years ago, the Catholic Church would decline precipitously, and lose much. But men and women like the unnamed letter-writer are the seeds of its future, and of its rebirth. This is also true for Protestants and Orthodox. Churches and church institutions can withstand the loss of those nominally committed to the mission, but they cannot withstand the loss of men and women like Archbishop Chaput’s correspondent.

If CUA should become a college where men like that do not want to send their children, what is its reason to exist? If Catholic colleges and universities are nothing more than lightly Catholicized versions of private secular institutions, what’s their point? In another couple of generations, the sentimentality that keeps young people seeking out Catholic schools because it seems like the family thing to do will have dissipated. What then?

UPDATE: A reader of this blog who is — let me put this delicately — in a position to know what’s going on at CUA, e-mails to say that this piece is a symbol of a fundamental conflict at CUA. On this person’s account, there is significant tension between a faction that wants the university to be less Catholic and more conventional, and a faction that wants to double down on Catholic identity. This reader identifies with the latter, which is why he finds the university an appealing place to work. He said that fortunately, the leadership of CUA is firmly committed to Catholicism.

The reader said not to be misled by consultants, who “exist primarily to compare you to other ‘peers’ so that you can behave like them.” The consultants in this case recommended that CUA use photos of the football team in its promotional materials, not students praying. The administration wisely ignored this advice. Said the e-mailer: “No student is going to come to CUA for football or for ‘fun’. But they might come for prayer.”

Bottom line: CUA does face some enrollment issues, but its leadership is strongly focused on Catholic mission and Catholic identity. This source is relatively young, and said this commitment makes CUA a great place to work for him. He said that whatever decline the US Catholic Church might be experiencing, there will always be faithful orthodox Catholics in the US looking for places to send their kids where the kids can get a reliable Catholic formation — and CUA intends to be one of them, and not part of the herd of assimilationist academies.

Great to hear.

UPDATE.2: Erin Manning comments:

Tuition, room, board, and fees at CUA are going to run you almost $61,000 a year. UD is up to a little over $57,000 a year for room, board and tuition (not counting the extra costs of the Rome semester). Most of the other “true Catholic colleges” are going to cost you between $35,000 and $60,000 a year in room, board, and tuition.

We were not blessed with a large family, but in some ways that hurts us more when it comes to financial aid.

I have no problem whatsoever with Catholic colleges and universities for those who can reasonably afford them. I urge caution for parents who would have to go into significant debt, or allow their children to do so, in order to go to these schools; the old “your education is an investment that will pay for itself!” mantra is disintegrating in the global economy (and especially if you study the humanities in a Catholic school), and you can only put off the day of reckoning by getting advanced degrees for so long. And I have no problem whatsoever warning parents who are on the poorer end of the economic spectrum that going deeply into debt (yourself and/or your child) while your child skips things like meals and health care to scrape up one more semester’s worth of Catholic Higher Ed. (while taking plenty of gap semesters/years to work crap jobs and live on a shoestring budget just to get that one more semester) makes absolutely no sense whatsoever. Some of you will get pressure from your local Catholic friends and/or family to make whatever “sacrifices” are necessary to send your kids to the good Catholic colleges (with dire warnings about how they will all become sexually profligate atheists if they set foot in a secular school), but what you probably don’t realize is that they most likely have resources you don’t (more income, more financial aid, grandparents who chip in, that sort of thing), and their idea of “sacrifice” is “my child doesn’t get as many expensive clothes as her classmates and has to put up with an Android phone,” not “my child ran out of money completely and has borrowed $20 from a classmate to purchase two weeks’ worth of food while she’s waiting for her last paycheck to get deposited.” (Which, by the way, was not something I actually ever told my parents about back in my day when that happened to me.)

Now, if a Catholic educational organization were to create and finance a community college type of entity where young Catholics could obtain an affordable associate’s degree that would meet the requirements to transfer into the local university system so they’d have two years of solid, Catholic-grounded humanities courses as well as some practical STEM classes before finishing up at State U., I’d be excited about that, and would probably support it wholeheartedly. The truth, though, is that for the most part Catholic high school and college education is for the relatively wealthy American Catholic families (and a handful of very poor kids who get full rides). CUA, like all the other Catholic universities, is competing for a niche market within a niche market; that is, for faithful Catholics who value higher Catholic education and expect orthodoxy AND who can afford around 60K per year per child (even if by “afford” we mean “cobble together enough aid to pay for what we can’t cover in cash). Truth is, there aren’t that many people who meet that description anymore, and the orthodox Catholic schools will be competing desperately for the same few slices of an already tiny pie, if they aren’t already.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.