Kintsugi Alison

I drove down to New Orleans last night to have dinner and spend the night with some old friends. It’s the first time we’ve seen each other since my divorce news, and they wanted to offer me some bourbon and sympathy. What I’m about to tell you I do so with the permission of the wife, “Alison” (not her real name).

Alison — middle to upper-middle class white person — is a survivor of childhood sexual abuse, which, of course, knows no class boundaries. She struggled for years to deal with it before finally getting the help she needed. Part of her recovery has been to involve herself in charity work helping families in severe crisis. This has become her passion. She’s an Uptown New Orleans lady who looks like everybody else walking around this part of the city, but this woman, I swear, is a saint. I mean it seriously. Working out of her own radical brokenness, Alison, a committed Evangelical Christian, has thrown herself into helping children who are even more vulnerable than she was.

When I said goodbye to her this morning, after hearing the story of one family she’s helping, I said to her, “My God, if you weren’t in their life, where would they be?”

She replied, “That’s exactly what made me do it. When I first heard about them, I said, ‘Lord, do I really want to wade into that mess?’ And I realized that if I just stood by and let it happen, those kids would have nobody advocating for them.”

This family is a black family. Four kids, I think, all by different fathers, but there is a man in the house, their mother’s longterm boyfriend, who seems like a good guy. They were homeless when Alison was put in contact with them through a charity she works for. They were living in a hotel on Chef Menteur Highway, which, said Alison, “is the human trafficking district of New Orleans.”

She explained that human trafficking — that is to say, trafficking in sex slaves — is “one of our big tourist draws in New Orleans” (she was being sarcastic). She said, “We have way more pedophiles in this society than people think.” She told me about a friend of hers who works in state government, on a task force fighting human trafficking, who goes into crowds when there are big sporting events in the city, and passes out leaflets warning people that the “girlfriend” they hire might be a sex slave.

“A lot of these people come to town and want prostitutes,” said Alison. “And a lot of them want ten year old girls.”

She then told me about a world that I only barely knew existed. And it was this world from which she was trying to save the children in that family.

But to do that, she had to help save the family from itself. She told the back story of how they used to live with the mother’s mother (that is, the grandmother of the kids). That woman was abusive, and stole the paychecks of her daughter, the children’s mother, and gambled them away. Finally they got out of that situation. The mom, though, “has no idea how to be a mother,” said Alison. She was never taught. Alison has to teach this poor woman basic things about how to live life — the kind of things that most of us take for granted.

When Alison first encountered them, she set up an escape plan for them to get out of that trafficking motel and into safe housing for six months, during which time they were supposed to figure out a plan for their lives. The six months came and went and … no plan. Alison says that they simply could not imagine the future, or imagine that they have any agency.

I forget the timeline as I write, but at some point the kids lived in the care of a distant relative who ran an unlicensed day care center. She abused these children — little children! — so badly that one of them ended up in the ICU. When the child protective services got involved, they found that the other children had bite marks on their torsos. This distant relative who ran a freaking day care, was abusing them in ways that other people couldn’t detect.

Eventually, Alison opened doors and got the children and their reunited parents moved to a town that’s safe. They didn’t want to go at first, saying, “they don’t like black people there.” Alison had to explain that a lot of black people lived there, and that the schools for the children would be almost entirely black.

This is just one family. Just one family. But, says Alison, this city, and this country, is full of people like them. Alison plans to spend the rest of her life pouring herself out to do what nobody did for her, growing up in a solid middle-class conservative Christian family: do her best to make sure the kids are safe.

Listening to Alison’s stories — and she works with other cases too — made me realize how completely unrealistic our discussion in this country is about race, class, and poverty. This is one reason why J.D. Vance’s Hillbilly Elegy struck such a chord in me: because he talked about white people who lived in many ways with the same internal social chaos as these black people Alison helps. One great strength of J.D.’s book — something that angered his liberal critics — is that he criticized his own people for their failures to thrive. For their drinking and drugging, and not showing up for work, and for creating a culture of failure.

Alison’s husband was telling me about this family his wife helps, and how so much of the brokenness and exploitation came from a “truth” of the family that the wicked grandmother told: that her daughter’s paycheck didn’t belong to her daughter, but to “the family,” which meant that Granny got to control it … and she gambled it away while they all lived in poverty. Granny exploited the idea that “family” means more than anything else. This went on for years before the young mother realized what was going on, and told Granny that you won’t be getting my paycheck anymore and taking it to the casino. Granny called child protective services and told them that her daughter was abusing the kids. They seized the children — this, because Granny wanted to punish her daughter for standing up for herself.

I told Alison’s husband about two extended families I know of back home — one black, and one white — that operate this way. How children raised in those family systems can ever break out of it is a mystery. One of these families I wrote about in Little Way. My late sister helped a student of hers do so. That student, who came from one of the poorest families in the parish, went on to get a graduate degree, and has built a successful life as a wife, mother, and professional out in California. I asked her after I interviewed her for the book if she ever thought about coming back to Louisiana. Never, she said: if she did, her family would eat her and her husband and their kids alive. This woman had been delivered from a culture of drink, drugs, and abuse — and could not afford to look back.

Family. The details she gave me about how the members of her clan treat each other made me realize that there is not enough private charity or government programs in the world to fix that kind of brokenness. Same with the white family clan I’m thinking of. At some point, something essential was lost. Me being me, I thought about the collapse of the western Roman Empire, and how total it was. As the Oxford archaeologist and historian Bryan Ward-Perkins has shown, when the Roman state fell apart in the West, the amount of basic human knowledge that was lost was massive.

I wonder if we are living in a failed society, in the sense that the systems that passed along basic social knowledge have been lost to large numbers of people, and are being lost. I’ve written here about how bizarre it was to go to a conservative Evangelical college about a decade ago — a predominantly white school in a fairly conservative part of the country — and to have a conversation with a professor who told me the thing that worried him most about his students was that they would not be able to form functional families. This mystified me. Why not? I asked.

“Because most of these kids have never seen one,” he replied. All the other professors around the table nodded.

(I am aware, of course, that I am making this point as a man whose wife is divorcing him, and whose children are now … well, you know. And yet, as regular readers know, I have said that even though I did not choose this path, I believe my wife chose the less bad option, given how long we had both been suffering in a marriage that long ago broke down irretrievably. We have the freedom today to end bad marriages — and even marriages between two people who are faithful Christians who believe in the sanctity of marriage can go bad. So much of the stability that we long for in the past depended on people having to absorb a hell of a lot of suffering, with no hope of relief. I believe that our inability to tolerate suffering is a big part of what’s wrong with our society and culture — but that said, that doesn’t mean that one must accept deep suffering in every instance as simply a fact of life.)

Anyway, what has happened to the poor is now moving up the social ladder, though in different ways. The very poor are homeless and living in fleabag motels on the Chef Menteur Highway, trying to keep their children from being trafficked. The middle class and the rich are trying to figure out how to keep their children from deciding that they are the opposite sex and want to cut their breasts or their balls off. As a people, we are forgetting the basic skills of how to be human. Don’t you think? I interviewed Prof. Ward-Perkins years ago, and he told me that it’s difficult for modern people to conceive of how total the loss of technical knowledge was when Rome fell. For instance, he said it took Europeans a thousand years to learn how to build roofs as well as the Romans.

That’s not likely to happen to us, thanks to technology. There will always be books that can teach us how to build roofs. But what about knowledge of how to raise a family? How to create stability? How to build a resilient society?

I’m not talking about utopia, please understand. We will always have evil with us. It’s in our nature. The kind of evils that adults visit on children, and that Alison was telling me about — the evils to the poor black family, and the evil that was done to her as a child by members of her extended family — are not a function of bad social systems, or poverty, or anything other than the evil that lurks inside every human heart. I firmly believe that the best we can do is build societies in which the instances of evil are limited, but it cannot be eliminated. An attempt to do so would create other evils. You could build a theocratic police state where vice is heavily policed, but think of all the other evils that trying to stamp out particular evils would create. Any proposed solution that ignores the urgent need for repentance, and the reformation of each individual’s heart, is a false one.

Solzhenitsyn famously said that one of the most important lessons he learned in the gulag is that the line between good and evil doesn’t run between social classes, but down the middle of every single human being’s heart. We are always looking for scapegoats. I was thinking on the drive back to Baton Rouge today of a person I know whose mother looked the other way while he was being abused by others in the family. He told me that to this day, she refuses to admit any responsibility for what was done to him. “It’s not that it’s her fault, exactly,” he once said. “But she had a part in it. She can’t say that she’s sorry. This is how she’s been all her life, blaming everybody else for all her failures.”

He no longer talks to his mom. My sense is that all he asks from her is that she say, “I’m sorry I failed you.” But she won’t. This is as old as Adam blaming Eve for making him taste of the forbidden fruit. Scapegoating is in our nature. Alison told me this morning that she and her mom are rebuilding their relationship, but it took a while, because her mom did not want to face her own role in the abuse that happened to her daughter (it was the same kind of deal: the mom should have recognized what was happening, but did not want to see the obvious signs, because that would have forced her to take responsibility to protect her child by offending other family members).

How much respect I have for Alison! She can never undo what was done to her, but she’s healing now — and she has used her own experience of deep suffering to reach out to others, especially children, to try to save them from some version of what happened to her. Alison has political views, and I’m quite sure she has ideas about what the state, and private society, can and should be doing that it’s not. But Alison is also a faithful Christian, and there is a certain realism about her Christianity. She doesn’t harbor illusions that all this brokenness can be fixed if we just adjust the technocratic formulas, or crusade sufficiently in the media against this or that social evil, or demonize this or that race, religion, or class of people. She believes that sin is real, and Jesus Christ, the God who entered into the human condition, and suffered as unjustly and as painfully as anyone suffered, is the only real hope for any of us. She is trying to be Christ to that poor family. She told me that on Mother’s Day, the mom of that family texted her to say, “You have taught me more about how to be a mother than my own mother ever did.” Alison, who has no children of her own, but whose heart was broken, and out of it pours love for the other broken people.

She got me to thinking on the drive home: how will I allow the broken heart I have over my divorce change me? How can I allow this suffering not to embitter me, or make me cynical, but rather more loving? If you read the thing I posted here about the small miracle I had in Jerusalem on Holy Thursday (see “A Resurrection in Jerusalem”), you’ll know that I spent Holy Week at the chapel built over Golgotha, where Jesus was crucified, praying for my wife, my kids, and myself. On that Thursday, I was at a different chapel, this one at the base of the stone hill that was Golgotha, and I felt the presence of Jesus at my right side. I wrote:

The morning after I found out that my wife was divorcing me, I came to Jerusalem. I have spent a lot of time atop Golgotha, praying for her, praying for me, praying for our kids. I have been grieving. God has given me an ability to see my wife as someone who has been suffering greatly too. I have not been able to muster anger at her. We are just so unbelievably exhausted from all this. Nine years of it.

So: as I sat in that silent crypt this morning, I thought about the sword in the stone, then I remembered that today is Holy Thursday, the day that Jesus Christ was taken in the Garden of Gethsemane to his trial. On this night, Peter drew his sword to protect the Lord from his enemies, but Jesus told him to put it away, and surrendered to his fate. Jesus knew that what was about to happen had to happen for all righteousness to be fulfilled.

I heard the inner voice say to me that now was the time to put away my sword — that is, to stop fighting for a restoration of the past. In fact, said the voice, I had done that at the monastery. I had made the long nine-year journey across the empty bath with the flame alight; now I needed to place it on the stone and be free. Then it hit me: that stone where I had just been praying was the stone that marks the spot (traditionally, if not necessarily literally) where the Romans discarded the Cross. The inner voice was telling me that the fight was over, that what was about to happen — meaning the dissolution of the marriage — had to happen.

But why? I asked. Why not just restore the marriage?

I didn’t wait for an answer, but banished the questions. I may never know, and that’s beside the point. Why did Jesus have to suffer and die? We are dealing with the deepest mysteries here.

Why doesn’t God smite the child traffickers and child molesters? Why doesn’t he punish the evil grandmothers who exploit their children? Why doesn’t he stop the white supremacist mass shooters before they can pull the trigger? You get nowhere going down this path. I think of my friend Michael, who is now dead. He was raped by the monsignor who was principal of his Catholic school when he was around eleven years old. This would have been in the 1960s. He told his working-class Irish Catholic mother what happened. She slapped him hard and told him never to speak ill of a priest. That was it. He became the sex slave of a priest who went on to become a bishop. Michael became a chronic alcoholic who compulsively sought out sex with men, often priests. Eventually, as an older man, he found sobriety.

He told me about how back in 2002, I think it was, a priest from somewhere in the Balkans came through New York to say some masses. This priest was purported to have some sort of mystical gifts of healing. The priest said mass at a big parish in Queens. Michael went to the mass, though the priest spoke no English. He was hoping for a miracle. Michael said he waited in line to get the priest’s blessing, and made sure that he was one of the last ones. He didn’t want to be greedy.

He knelt to receive the blessing, then began making his way toward the exit. Before he got to the door, an English-speaking assistant of the Balkan priest ran to him, took him by the arm, and said, “Father wants me to tell you that the Holy Virgin saw your suffering there, at the hands of that priest. She was there with you, and suffered too.”

When Michael told me that, he was crying. Those words had been so healing to him. My unspoken thought was, But why didn’t she strike down the evil monsignor? Michael, he was just grateful that he had been seen, and that the Mother of God shared his suffering. That was enough for him.

It is enough for me, in my own suffering, to know Jesus was there with me, and in some way, this was part of His plan. My suffering is very, very small compared to what Alison endured, and to what the family she’s helping endures. Alison can’t fix all that is wrong with that poor family. But she can try to fix what she can, and she can continue to walk with them, and share their suffering. What else is there?

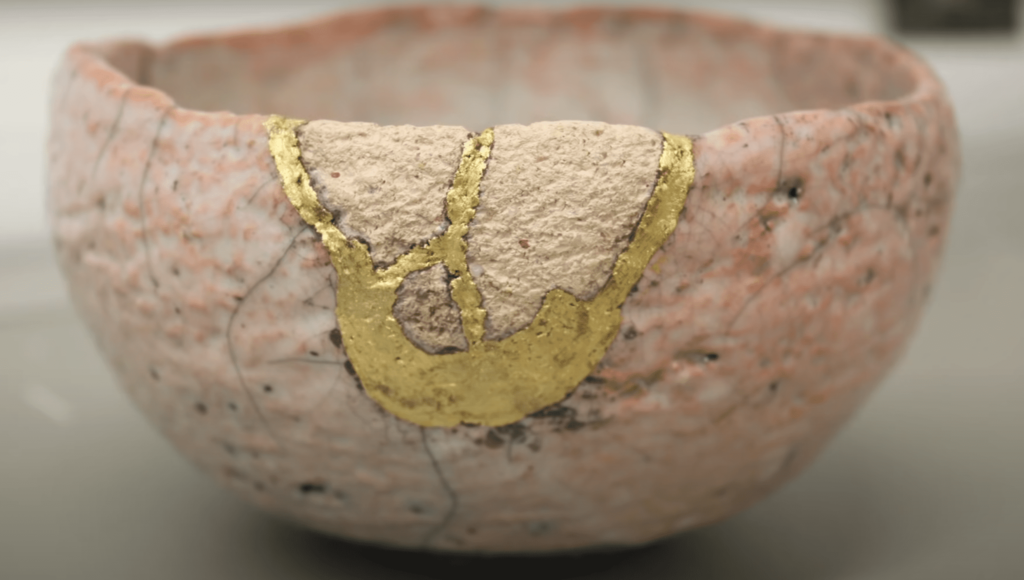

We will never be able to straighten every crooked line, and right every wrong, though that is certainly no excuse for not acting when we have the capability to do so. We are going to need a lot more Alisons in the days to come. And by the way, in the subhed of this piece, I said, “What a once-broken and abused woman is doing to redeem her suffering.” Alison would be the first one to correct me. She would have me say, “What a once-broken and abused woman is allowing Christ to do through her to redeem her suffering.” She has in her kitchen a kintsugi vase — it’s a Japanese style of pottery that’s about the art of embracing damage. It’s a sign of her new wholeness.

UPDATE: The commenter Lord Karth, who is an upstate New York lawyer, writes:

It’s worse than you think, Mr. Dreher.

In my 34 years of Family Court practice, I have had to tell any number of people that they had to make a choice between abusive/drug-using/alcoholic “significant others” and getting/keeping their children. In the first dozen years or so, I tended to get angry looks. The clients (mostly women) pretty much knew what they were doing was not good. They didn’t like being called on it.

In the last dozen years or so, the reactions have changed. The most common reaction I get these days is stunned, uncomprehending surprise. They honestly do not know that the situations are bad, either for themselves or the children.

They simply do not get it. I could be speaking Sanskrit for all they comprehend.

You don’t know the half of it, Mr. Dreher. You really and truly don’t. Come up and make the rounds of CNY Family Courts with me. I’ll show you situations that make the ones you describe look like a picnic.

That is the change: that so many of us have lost the capacity to discern good and evil in these matters. A white friend who, until relatively recently, lived for decades in a black part of Baton Rouge (he remained in the house his parents lived in, even after white flight), told me that the only strings holding together any semblance of healthy social order in his old neighborhood were the grandparents’ generation — and they are dying out. They are the only ones with any memory of the Before Times. It sounds like this is fast becoming the situation for all of us in America. Remember the quote above from the Evangelical college professor, who said that his (mostly white) students had never experienced a stable family.

Wanting to protect our children from that is one of the reasons my wife and I struggled so hard, and for so long, to preserve our failing marriage. What grief, all around… .

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.