College Football and the Open Society

College football is antithetical to the open society. That’s why the open society needs it.

In 1905, college football was almost banned for what Theodore Roosevelt called its “brutality and foul play.” Nineteen players died that season (ninety-five would be the modern equivalent), and games featured punching, kicking, choking, and eye-gouging. Safety regulations saved not just lives but the sport.

On reflection, however, it is puzzling that even a reformed college football has been permitted to survive in this country. The culture and practice of the sport are, in important ways, antithetical to the principles of a liberal society.

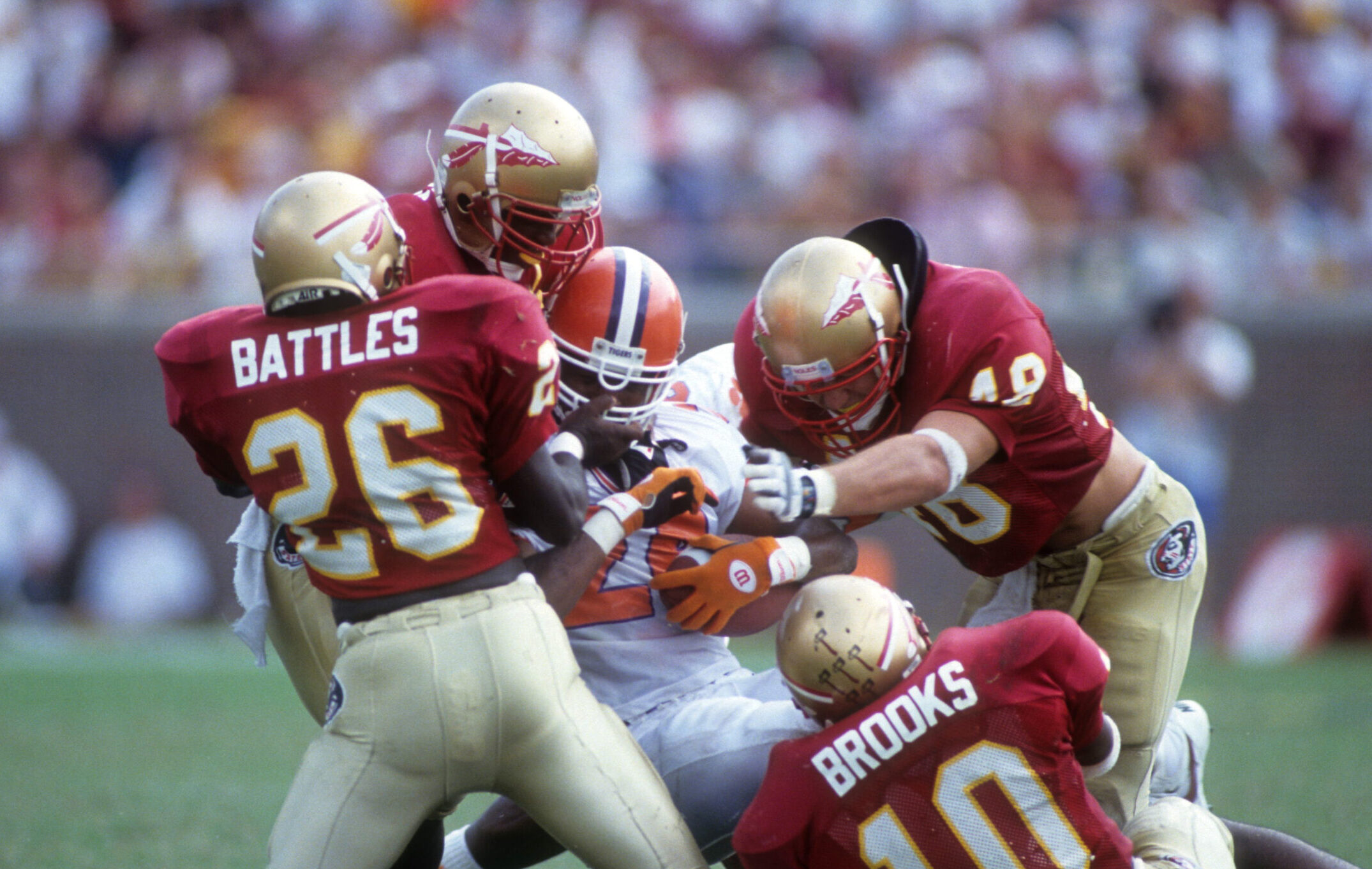

For one thing, it is an emphatically male sport—exclusively among players, almost exclusively among personnel, and overwhelmingly among fans. Specifically, football centers inescapably on savage male violence. College football is intensely tribal, pitting fanbases against each other in a zero-sum arena that extends beyond the field, into bars, living rooms, and, today, social media. Storied rivalries entrench implacable, unreasoning hatred of the Other, compounded with each year, and blind loyalty that denies any wrong or failing in one’s own camp.

Moreover, college football is strikingly pre-modern, even classical. Hero-worship abounds; legendary Coach Bear Bryant’s standing in Alabama is very slightly lower than God’s. The group of experts whose job it is to impartially enforce neutral procedure—referees—are the only beings fans loathe more than rival partisans. Starting with the very shape of the stadiums, analogies to Rome’s gladiatorial games are just too easy.

The sport is immoderate in its loyalties: A seething mob of nigh on 100,000 rocks the stands, caught up in jubilation or despair at achievements not their own, while bloodthirsty boos rain from the beer-sodden fans. On game-day, the colors of both team and country are hoisted, the warriors fitted with armor, the band drums up passions, the very air pulses with blood-red light, fighter jets soar overhead, and mascots stab swords into the turf, fly around the stadium, or ride with burning spears. Altogether, it’s hardly a scene of Enlightenment.

Does this atavistic blindspot in a liberal culture serve any beneficial purposes?

One might defend college football’s brutality as a handy outlet for destructive but ineradicable primal urges that, if not sated somewhere, may bleed into politics. Whereas 2 Samuel 11:1 tells us that spring was “the time when kings go out to battle,” now autumn is the time when teams go out to battle. Better to angrily relitigate whether J.T. Barrett got the first down or not against Michigan in 2016 than the Treaty of Versailles; better for Alabama to lay bogus claim to disputed national championships in the 1930s than for China to claim Taiwan; better for a Georgian to believe the 2018 National Championship Game was stolen than the 2020 election.

College football fans know, however, that their beloved sport is not a necessary evil. It is far less an outlet for destructive urges than a training ground for virtues that a liberal society particularly needs.

For one thing, college fandom creates, consciously or not, a profound living relationship to the past. Most people inherit their team loyalties from their fathers, and I speak for thousands when I say that shared agony and ecstasy over the fate of our team has created a special bond between my father and me—a bond that will last and renew itself each September that the Georgia Bulldogs suit up. Indeed, some of the primal, “ugly” parts of the game go the furthest toward tightening this bond: My dad (a kind, humble Christian man) instilled in me a deep reverence for Herschel Walker and the 1980 national championship-winning team, and taught me earnestly that I must hate the Florida Gators with zeal.

Being a fan prompts many people with little interest in history to acquire encyclopedic knowledge of the past by exploring their team’s lore—usually learning at a father’s feet. Michael Brendan Dougherty has written that “a nation exists in the things that a father gives to his children.” The same can be said of the mini-nation of a southeastern fanbase.

College football allegiances also forge a connection to place that is increasingly uncommon. Particularly in the Southeastern Conference (SEC—easily the most dominant conference), football has a rich regional flair, apparent even to TV viewers in the coaches’ drawls, the local barbecue highlighted by ESPN at halftime, and the blasting of tunes like “Dixieland Delight” over the stadium speakers. Research shows that college football fandom grows more intense the further you get from a large city, enjoying most popularity in the Midwest and of course, the South. In other words, it flourishes where people are the most rooted.

The sport also cultivates loyalty to institutions over individuals in a way that professional sports often do not. There are many LeBron James fans who root for whatever team he happens to be on; no such phenomenon exists in college football, where there is regular, frequent personnel turnover as coaches leave and players graduate. The universities are the constant. Even as fans turn on bad coaches and demand the benching of inconsistent quarterbacks, loyalty to the program is unshaken—indeed, this very loyalty feeds rage at individuals who undermine its success.

The attributes that college football inculcates are not highly esteemed in America’s power centers. A relationship to the past is superfluous in light of expected progress; love of place is narrow-minded; loyalty to institutions constrains individuality. Yet these virtues (for virtues they are), far from being undesirable, are necessary for our political life—even and perhaps especially for political life in a liberal society.

In a recent essay, Matthew Rose highlighted philosopher Leo Strauss’s conviction that the open society (characterized by dynamism, individualism, and the elevation of reason over tradition) badly needs virtues cultivated by its antithesis, the closed society: “He argued that many virtues essential to liberalism are best understood in the moral traditions that are most opposed to liberalism.”

Liberal culture “places bodily safety and well-being at its political center” and “diminishes the soul’s need for moral risk,” but freedom and self-government are only possible when citizens orient themselves towards higher duties than self-interest. Moreover, the open society domesticates the spiritedness, or thumos, that rules the honor cultures of the closed society, because its violent tendencies are dangerous to peaceful coexistence and the harmonization of interests. But thumos is also the source of virtues that a voluntary society sorely requires. A society that deflates thumos may be less violent, but it will struggle to find enough spirited souls who are willing to lay down their lives for it. Small wonder that our military is experiencing a recruiting crisis.

And small wonder, too, that those who still volunteer for the military—and have done so historically—hail from the rural, rooted, violent, and past-oriented regions in which college football is a second religion (sometimes a first, these days). The cultures that turn out in force on fall Saturdays to drink and holler as armor-clad young men collide, and produce people willing to poison rivals’ sacred trees, also supply an outsized share of America’s military recruits. These regions retain strong characteristics of the closed society, both for good and ill—and the bad and good can’t be unlinked.

Yet perhaps the open society is set to take its long, slow toll. In the past several years, college football has become more subject to market forces, to the detriment of its institutional and regional nature. The rise of name, image and likeness (NIL) compensation for players—a logical step after years of free agency for coaches—has opened up a Wild West in which boosters bid for elite recruits, and points to a future in which athletes are employees. The transfer portal has allowed top players to move around the country with impunity, rendering commitments to particularly programs transitory and secondary.

Subscribe Today

Get daily emails in your inbox

Sports betting has consumed college football media: It feels like many podcasts devote as much attention to over-unders and locks of the week as to actual games. Dizzying conference realignment driven by politicking over lucrative TV deals has diluted the regional character of certain conferences, while destroying some leagues altogether: Oregon, Washington, USC, and UCLA will leave the carnage of the Pac-12 to compete in the same conference as Penn State, Rutgers, and Maryland. Realignment has also killed traditional rivalries such as Pitt-West Virginia and Nebraska-Oklahoma. There’s even talk of programs courting private equity investment to boost revenue.

Writing in The Public Interest in 1987, political scientist Thomas Pangle concluded that certain “revolutionary consequences” of America’s natural-rights public philosophy had “remained largely hidden or restrained by habits and institutions that were only very gradually being corroded by the acid of modern natural rights.” He chiefly had the traditional family in mind; could college football become another so corroded institution?

Maybe the virtues of the traditional college game will adapt seamlessly to new circumstances (Texas A&M boosters showed fanatical institutional loyalty, as they basically bought the highest-rated recruiting class of all time via NIL hookups for athletes). Maybe the SEC, by combining sustained dominance with enduring regional rootedness, will lead the sport through the market’s deadly snares. But if college football severs its living ties with the past to remake itself in the image of mammon, then the open society will have dealt another sad blow to its own foundation.

Comments