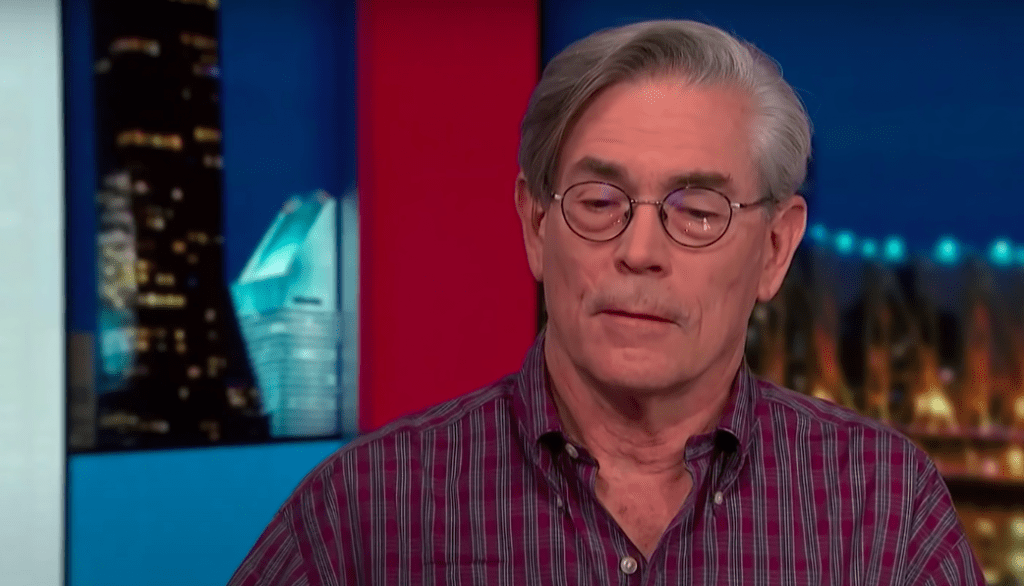

Donald McNeil Tells His Side

From about 2002, when the Catholic Church’s sex abuse scandal broke, until around the end of that decade, the experience of reading the newspaper was to risk yet another reminder that no, even now we haven’t seen the totality of this institution’s corruption.

I feel that way about each new advance in the New York Times scandal: the destruction of the newspaper’s standards at the hands of Wokeness. Today’s four-part Medium account of Donald G. McNeil’s forced resignation, as told by Donald G. McNeil, is one of those days.

McNeil withheld publication until after his last official day at the Times. It’s safe to say that after today, he will not be welcome in that building. The portrait he paints of the Times is a familiar one — that the newsroom has been taken over by woke militants, and the paper’s senior leadership, like dissenters, are terrified of them — but the detail McNeil gives about the events that ended his career makes publisher A.G. Sulzberger and editor-in-chief Dean Baquet look even more gutless.

Here’s Part One, which introduces the issue.

Here’s Part Two: what happened on January 28, when McNeil, the Times’s lead Covid writer and a journalist of 40 years’ experience at the paper, received an e-mail from a Daily Beast reporter informing him they were going to do a story about him and the Times-sponsored Peru trip he took, accompanying a group of rich prep school kids (none black).

From that section, McNeil says this is the draft of the responses he made to the Beast reporter’s questions, but that the Times would not let him send:

1. Yes, I did use the word, in this context: A student asked me if I thought her high school’s administration was right to suspend a classmate of hers for using the word in a video she’d made in eighth grade. I said “Did she actually call someone a “(offending word”? Or was she singing a rap song or quoting a book title or something?” When the student explained that it was the student, who was white and Jewish, sitting with a black friend and the two were jokingly insulting each other by calling each other offensive names for a black person and a Jew, I said “She was suspended for that? Two years later? No, I don’t think suspension was warranted. Somebody should have talked to her, but any school administrator should know that 12-year-olds say dumb things. It’s part of growing up.”

2. I was never asked if I believed in white privilege. As someone who lived in South Africa in the 1990’s and has reported in Africa almost every year since, I have a clearer idea than most Americans of white privilege. I was asked if I believed in systemic racism. I answered words to the effect of: “Yeah, of course, but tell me which system we’re talking about. The U.S. military? The L.A.P.D.? The New York Times? They’re all different.”

3. The question about blackface was part of a discussion of cultural appropriation. The students felt that it was never, ever appropriate for any white person to adopt anything from another culture — not clothes, not music, not anything. I counter-argued that all cultures grow by adopting from others. I gave examples — gunpowder and paper. I said I was a San Franciscan, and we invented blue jeans. Did that mean they — East Coast private school students — couldn’t wear blue jeans? I said we were in Peru, and the tomato came from Peru. Did that mean that Italians had to stop using tomatoes? That they had to stop eating pizza? Then one of the students said: “Does that mean that blackface is OK?” I said “No, not normally — but is it OK for black people to wear blackface?” “The student, sounding outraged, said “Black people don’t wear blackface!” I said “In South Africa, they absolutely do. The so-called colored people in Cape Town have a festival every year called the Coon Carnival* where they wear blackface, play Dixieland music and wear striped jackets. It started when a minstrel show came to South Africa in the early 1900’s. Americans who visit South Africa tell them they’re offended they shouldn’t do it, and they answer ‘Buzz off. This is our culture now. Don’t come here from America and tell us what to do.’ So what do you say to them? Is it up to you, a white American, to tell black South Africans what is and isn’t their culture?”

*(Since writing that email, I’ve learned from YouTube that the event has been renamed the Minstrel Carnival and, while face paint is common, blackface is rarer.)

McNeil adds:

Since this episode began, I have been willing to apologize for any actual offense I’d given — but not to agree to the Beast’s characterization of me, which I felt made me sound like a drunken racist roaring around Peru insulting everyone in sight.

If the Times had not panicked and I had been allowed to send some version of that, perhaps the Beast would have rewritten or even spiked its story. Almost undoubtedly, the reaction inside the Times itself would have been different.

The news broke, but McNeil says he didn’t realize how seriously the Times senior management took the allegations.

Top management had met by Zoom with black reporters. There were department-by-department Zoom meetings about it. Slack channels were aflame, which I didn’t know because I avoid Slack unless I’m forced to use it.

Racially centered Zoom meetings, and department-by-department Zoom meetings, because of these piddly allegations — allegations the Times had already investigated in 2019, and cleared McNeil of wrongdoing! Who would want to work in a snake pit like that? Want to move somebody out of a coveted slot, and your target is vulnerable because of race, age, sex, or some combination thereof? Just make an accusation, or put someone else up to it.

More:

On Monday, February 1 — by coincidence, my birthday — Dean [Baquet] and Carolyn Ryan called me at about 10:30 A.M.

My notes of the conversation are sparser than I normally take, but I also recounted it right afterward to a friend, so I think this is accurate.

As I remember it, Dean started off by saying “Donald, you had a great year — you really owned the story of the pandemic….”

As soon as I realized he was talking in the past tense, I became tense and started taking notes.

“Donald, I know you,” he went on. “I know you’re not a racist. We’re going ahead with your Pulitzer. We’re writing to the board telling them we looked into this two years ago.”

“But Donald, you’ve lost the newsroom. People are hurt. People are saying they won’t work with you because you didn’t apologize.”

“I did write an apology,” I said. “I sent it to you Friday night. I sent another paragraph on Saturday morning. Didn’t you get it?”

Dean didn’t answer.

“I saw it,” Carolyn said.

“But Donald,” Dean said, “you’ve lost the newsroom. A lot of your colleagues are hurt. A lot of them won’t work with you. Thank you for writing the apology. But we’d like you to consider adding to it that you’re leaving.”

“WHAT?” I said loudly. “ARE YOU KIDDING? You want me to leave after 40-plus years? Over this? You know this is bullshit. You know you looked into it and I didn’t do the things they said I did, I wasn’t some crazy racist, I was just answering the kids’ questions.”

“Donald, you’ve lost the newsroom. People won’t work with you.”

“What are you talking about?” I said. “Since when do we get to choose who we work with?”

“Donald, you’ve had a great year, you’re still up for a Pulitzer.”

“And I’m supposed to what — call in to the ceremony from my retirement home?”

Carolyn stepped in: “Donald, there are other complaints that you made people uncomfortable. X, Y and Z.”

I remember looking at the snow in my garden.

“May I know exactly what X, Y and Z are? And who said I did X, Y and Z? I’m happy to answer anything — but I have to know what I’m being accused of.”

Neither of them responded. To me, it felt like an attempt to intimidate me.

“Let me give you an alternative view of who’s ‘lost the newsroom,’” I said. “I’ve been getting emails and calls from bureaus all over the world saying, “Hang in there, you’re getting screwed.” People are outraged at how I’m being trashed in the press and by the Times. If you fire me over this, you’re going to lose everybody over age 40 at the paper, all the grownups. All your bureau chiefs, all your Washington reporters, all your Pulitzer winners. Especially once they realize how innocuous what I really said was and that you didn’t find it a firing offense in 2019. And they’ll talk to every media columnist in town. The right wing will have a field day.”

“We’re not firing you,” Dean said. “We’re asking you to consider resigning.”

“You’re twisting my arm.”

“We’re not twisting your arm.”

“Just mentioning it, just bringing it up, is twisting my arm. Nobody in 45 years has suggested I resign. Charlotte has threatened to fire me a couple of times, but that’s different. That was always bullshit. But nobody’s ever suggested I resign. I should shut up and get a lawyer. I need a lawyer.”

Dean and Carolyn seemed to pretend to not hear that, either.

“We’re not twisting your arm. We’re asking you to consider it.”

“No. I’m not considering it. I’m not just quitting like this.”

The conversation then trailed to an end, with them saying “consider it” and me saying no.

Here’s Part 3, covering the paper’s investigation of the 2019 Peru trip allegations.

From an e-mail McNeil says he sent to the friend who recruits Times reporters for these voyages serving as experts:

You should warn anyone you recruit that the Times will treat any crazy allegation — even one by a 15-year-old — as a possibly fireable offense.

I used to love working here. Now I’m so discouraged. Such a mean, spiteful, vengeful place where everyone is looking over his/her shoulder. Even Al Siegal — Mr. Critical — had a sense of humor and balance.

Folks this is why we all need to pay attention to what happens at the Times. Because the Woke have the power to destroy people’s careers, they will destroy the workplace. This man, McNeil, had been at that newspaper for his entire career, and had reported for them from all over the world. None of that mattered. They sold him out because he’s an old white man, and though none of his privileged prep school accusers are black, some NYT employees of color were now refusing to work with him. Over mere accusations.

Here’s a part from the meeting between McNeil and the NYT lawyer (who has two strong potential conflicts of interest, according to evidence presented by McNeil):

Charlotte: “Did you say something about picking up the white mans’ burden?”

Me: “Yes. And a student got upset. But I explained it to her. I was quoting Kipling. I’m not sure the student had ever heard of Kipling.” [I’ll explain this in the next section.]

More:

Charlotte: “OK, let’s move on. Did you insult a shaman?”

“No. I didn’t insult anybody. Which shaman? There were two shamans, an Amazonian one and an Incan one. Do you know which one they mean?”

“Did you insult or make fun of either of them?”

“No! I actually really respected the Amazonian one. He knew a lot about herbs. I interviewed him afterward, and I took notes and took his picture and asked him if I could quote him in the paper some day. He seemed very happy about it. The other one, I didn’t take so seriously. He seemed like kind of a rent-a-shaman for tourists. He did a ceremony for us, but he also came back to the hotel to sell souvenirs.”

“Did you generally say disrespectful things about shamans?”

“Well, yes and no. I thought there was too much focus on shamans and alternative medicine and herbs and stuff like that on the trip. This trip is supposed to be about rural health — that’s why I’m the expert. But this year’s trip was different from last year’s. There was a lot of focus on shamanism, and local plants and customs… Look, I’m not completely dismissive of this stuff. I’ve interviewed shamans and witch doctors and sangomas and nyangas or whatever you want to call local healers. I’ve spent the night in a sangoma’s hut talking about AIDS. They often know a lot of plant medicine, and they understand the psychology of their patients, and a lot of what they do is about treating beliefs — many rural people in Africa and Latin America think disease is caused by curses, not germs, and witch doctors lift curses. But Westerners romanticize that stuff, and these kids definitely did. Some of it’s helpful and some of it’s harmless and some of it’s dangerous. For example — and I talked to them about this — it used to be the tradition in Peru that, when a baby was born and you cut the umbilical cord, you put a lump of dung on the stump. Llama dung or goat dung or whatever. Well, that kills a lot of babies from tetanus. I know a doctor from Cornell who told me it was one of the leading causes of neonatal mortality in Peru. That’s one of the reasons the Peruvian government actually fines women who don’t travel to government clinics to give birth. Now, that sounds really brutal to American kids who think home birth is this cool, wonderful thing — but it saves lives. So, yeah, I did not show total respect for local traditions. Because some of them kill babies.”

“And I also had a discussion on the bus in front of the students with one of the leaders, who was a grad student in plant biology. He was really into ayahuasca, which is this psychedelic brew they drink in the Amazon. He wanted to do a study giving it to people, and I was going ‘Whoa, whoa, whoa, that’s not how you do a clinical trial. You can’t just brew up a batch of psychoactive herbs and give it to people — you’re going to get people flipping out, you might get suicides. That’s totally unethical. You have to figure out what the active ingredients are, and give them to people under controlled circumstances, and have a placebo group.’ So I’m sure I came across as the old fuddy-duddy defending Western medicine. So sue me. But that’s how I feel. That’s what I was there for — to talk about real medicine, not shamanism.”

Charlotte: “Did you sing a Boy Scout song during a shaman ceremony?”

“What??? Did I sing a Boy Scout song? No, I don’t think so. What Boy Scout song?”

“I don’t know.”

“Um…. I don’t know what to say.”

I thought for a minute.

“Was it “I Wear My Pink Pajamas in the Summer When It’s Hot?”

“I don’t know. Did you sing that?”

“No, I don’t think I sang that. I can’t think of any reason I would have sung it. Was it “The Monkey He Got Drunk?” I don’t think I sang that one either. But those are the only two songs I can remember from Boy Scout camp. I mean, I sang them to my kids, but I didn’t sing them on this trip.”

“I don’t know.”

“OK, sorry. I don’t know either.”

This is the level to which the storied New York Times allows itself to be degraded and intimidated by newsroom mobs. This is the level to which they push around a worker who has given four decades of his life to the place, and whose work has been so good this past year they were going to nominate him for a Pulitzer.

You’ll want to read all of Part 4 as well. Like I said, the general outlines of the case we already know, but the details he fills in are damning about the Times newsroom, which sounds like a sick and twisted place to work. The Times’s internal inquisitor asked this old man McNeil if he had made fun of a student’s town — this, after one of the teenage mean girls interpreted his and a Boston student’s joke-teasing each other about the Yankees/Red Sox rival. If a reporter refused to work alongside another reporter facing these penny-ante accusations, that first reporter ought to be fired for insubordination. But as we see time and time again, the Times‘ leadership is too terrified of the newsroom to stand by expendable old white men like McNeil, the Pulitzer nominee pushed out because a bunch of posh progressive schoolgirls threw a hissy fit.

If I worked for the Times and hoped not to be involuntarily severed from its employ, I would ask for a transfer to the farthest bureau away from the home office as I could stand, and I would limit my interactions with my co-workers as strictly as possible, and I would never take initiative in the office, because the quieter I am, maybe the less they would notice me, and the less at risk I would be that a false accusation of Wokeness heresy would destroy my career.

On second thought, who would want to stay at a company like that?

UPDATE:

The Donald McNeil NYT dustup and the Smith story from last week share two things: the language of a moral panic around race being used to perpetuate class hierarchy, and adults who should know better ceding moral leadership to children who should not be expected to know anything.

— Batya Ungar-Sargon (@bungarsargon) March 1, 2021

UPDATE.2: A reader writes:

Thanks for your posting on McNeil.

I read all 4 Parts with growing anger — not just at the New York Times, but also at the ambushing of McNeil by the “posh progressive school girls” who “threw a hissy fit” as you put it.

In reading McNeil’s postings, I noticed that one of the prime prep school girls went to Andover [Phillips Academy, in Andover, MA].

I was quite upset at her uncritical, arrogant, unthinking political brainwashing. What the hell are they teaching at Andover?

So?

I am graduate of Andover (about the same time Bill Belichick graduated!) and have always been grateful for my years there, the outstanding faculty, my fellow students, and the superb education

that followed me to a top University, multiple graduate degrees, a career in the military, a PhD, and almost two decades of teaching Political Science and International Relations.It was tough, and a significant financial burden on my parents.

I have NEVER been ashamed or embarrassed about my Andover education or about the school. I have been immensely proud of MY prep school.

Until now.

Why would I give this Woke Fortress any support to further the ongoing destruction of our institutions? I shall not.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.