What if Custer Were A Lone Survivor?

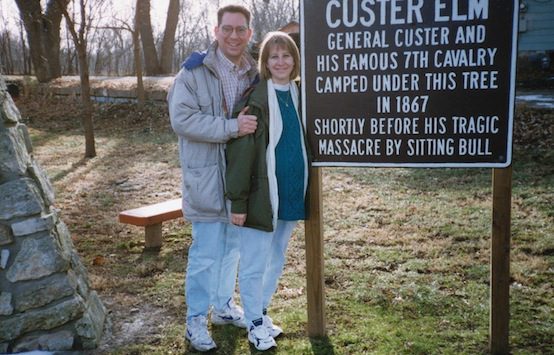

Sometime in the late fall of 1998, my pregnant (our first child) wife and I drove from Kansas City to Hutchinson, Kansas. En route, we stopped at Council Grove, an old, homey eastern Kansas town in the Flint Hills, once a part of the Sante Fe Trail. Somewhat famously, there’s an oak tree in town known as “the Custer Elm.” Whether it’s still there or not, I have no idea, but the sign that accompanied the elm read: “General Custer and his famous 7th Cavalry camped under this tree in 1867 shortly before his tragic massacre by Sitting Bull.” My wife and I laughed and laughed. Being bizarre history nerds, we thought that was hilarious. First, neither of us thought much of Custer as a human being. Second, Custer did not meet his doom until 1876. If nine years equates with “shortly” we wondered if the author of the sign had an Elvish life span. And, third, Crazy Horse, not Sitting Bull, killed Custer. Sitting Bull wasn’t even at the Battle of Little Bighorn. He was—befitting his position as medicine man—on home guard duty, protecting the Sioux villages during the battle. Please don’t get me wrong. Neither my wife nor I are cynical, nor do we fail to appreciate how much Kansans love their history. Being a native Kansan, I know very well how much Kansans appreciate their history. It’s hard to drive more than five miles without hitting a spot of some historical significance, marked and described for any and all travelers and wanderers across the Wheat State.

On a serious note, the dreadfully mistaken sign promoted a rather deep discussion about the nature of history, what we can know, what we cannot know, and what we have to accept—in necessary humility—as absent from the record and subject, then, to individual interpretation.

In a far more humorous vein, H.W. Crocker III addresses every one of these questions—though, often, in sideways, non-linear, indirect way—in his most recent novel, Armstrong, the first of his “Custer of the West” series. As I had a chance to mention a week or so ago at The American Conservative (and please indulge me as I obnoxiously quote myself):

A satirical alternative history about Michigan’s own George Armstrong Custer, simply and cleverly entitled Armstrong. In Crocker’s world, Custer survived a butchering by Crazy Horse at the Battle of Little Bighorn and has become a Victorian paladin and celebrity, doing everything over the top and then some more beyond the top. Crocker knows his history, so his anti-history is knock-down, pain in the stomach, hilarious.

I quote this not to be troublesome and arrogant, but to note that my views of a few weeks ago have only strengthened. Since finishing that book, I have given it much thought. Indeed, it keeps hovering over my other thoughts, and it has promoted me to ask a whole series of questions about the nature of history. Yes, the kind of questions that sign in Council Grove first posed almost two decades ago.

Without hyperbole, Crocker’s Armstrong caused so much laughter—as well as thought—that my sides and stomach did actually hurt. The model of the book is rather clearly Mark Twain’s Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. Considering Twain’s standing in 19th century American literature, I do not make this comparison lightly. That book, too, at least until its horrific and brutal ending, has given me laughter fits for much of my adult life. Crocker’s wit is certainly as good as Twain’s, amazingly enough, as both share the talent of poking fun without destroying. More on this later in the review. And, it’s not just Twain that one thinks of with Crocker’s novel. There’s also a more than a bit—often quite explicit—of Yellow Journalism, dime store fiction, Pulp, Batman, and even Kurt Vonnegut, Joseph Heller, and Flannery O’Connor in here as well. Outside of the written word, there’s quite a bit of cinema, too, but mostly of Zelig-like quality. Yet, if there was one movie that most will probably think of when reading Armstrong, it’s Dances with Wolves. Counter that sappy, feel-good-leftism, and New Agey Dances, however, Crocker turns Kevin Costner on his head. This is Dances with Wolves if written by Bill Gaines. If I’ve not expressed it well yet, let me blunt. This novel is over the top. And, mightily and gloriously so. Yet, even within the slap-stick outrageousness, there lurk and hover very meaningful and subtle points and comments. In other words, Crocker has produced a fictional masterpiece.

As noted above, the novel begins in June 25, 1876, the day of the massacre at Little Bighorn in Montana. On that day, it should be remembered, George Armstrong Custer unwittingly led part of the Seventh Cavalry into a trap. Frustrated by his post-Civil War career, Custer was often hotheaded, arrogant, and reckless. Those qualities (or lack thereof) caught up to him and, sadly, the men under his command on that day, as Crazy Horse led a pan-Indian coalition against the American invaders. Regardless of what is P.C. and what is not in 2018, the Indians were clearly the defenders, nobly rejecting the invasion while attempting to protect home and hearth. Their victory, though decisive, proved fleeting, as the waves of emigrants and their livestock would soon overcome the Plains Indians, no matter how noble they might be. It should also be remembered that, whatever his failings, Custer had been a true hero in the American Civil War. On July 3, 1863, in particular, he had led his men against those of Confederate Jeb Stuart, preventing the latter from assaulting the rear of Union lines at Gettysburg. The goal—at least as Robert E. Lee had envisioned it—was for Stuart’s cavalry to hit the center rear of Union lines just as Pickett’s men hit the front of the line. In a several hour cock of the walk, medieval style joust and dual between Union and Confederate cavalries in the East Field, Custer prevented aid from reaching Pickett and Lee. Simply put, Custer had mattered. By 1876, not so much.

Crocker creates a world in which Custer alone—at least among American military—survived that day, having been protected by Rachel, a white captive of the fictional Boyanama (!) band of Sioux. She claimed Custer as her slave, but he claimed her as his ward. As part of his captivity, the Sioux tattooed his arm, drawing a picture of his beloved wife, Libby on his biceps with the motto around it: “Born to Ride.” Escaping his captors, he decides that he must remain incognito, hoping to clear his name after the disaster at Little Bighorn. During the novel, in fact, he takes many names, all of them hilarious. The most frequent name he takes, however, is Armstrong Armstrong (yes, you read that correctly), thus the title of the novel.

Over ten chapters, Custer’s adventures never cease. From Sioux captive to Chorus girl to mock Indian to fake U.S. Marshall, Custer finds himself leading a group of enslaved victims in Bloody Gulch, Montana, a company town controlled brutally from the top down by one ruthless man and scoundrel, Larson. Interestingly enough, this man claims to be empowered by the U.S. government to hold such authority. Custer seemingly accepts this, also claiming to be empowered by the U.S. government. He rationalizes this as acceptable because of his hatred of all things Republican and U.S. Grant-related. Larson is a Republican, and he, Custer, a Democrat. When Rachel proclaims him a “liberator” in the vein of Abraham Lincoln, he quickly corrects her. “No, Rachel, not like Lincoln. He was a Republican. What this country needs is a good Democrat in favor of lower taxes, a return to sound money, free trade, a smaller reformed government that spends more on the army, and honest administration—especially after two terms of that baboon Grant.”

Don’t make too much of the quote, though. This is not a political book. Not in the least. It’s a book of adventure and social commentary. The social commentary, though, is simply drop-dead hilarious. Among Custer’s allies in the book are a former Confederate officer and dandy, a Latin-speaking, Catholic Crow Indian, a number of Chinese acrobats, and seemingly unlimited beautiful women—all of whom seemingly swoon over Custer’s manliness. At one subtle moment, Custer perks up considerably when he learns that having been inducted into the Boyanama Sioux might very well allow him to have multiple wives. Though Crocker takes this no further, it’s pretty clear that Custer hopes this might happen.

In the social commentary that pervades the whole story, much as Mark Twain does in Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court, Crocker plays with radically politically incorrect stereotyping. Yet, the humor to be found—gut holding at times—is not because Crocker’s depictions are shocking (they are), but because they’re hilarious. As a gifted writer and thinker, Crocker’s stereotypes artfully reveal the true essence of humanity, the individual person, and virtue. It’s a stunning accomplishment, frankly.

Finally, it has to be noted that the entire book is written as a long letter to his faithful and devoted wife, Libby, letting her know that he survived Little Bighorn as well as retelling his manly adventures. For some bizarre and funny reason, Custer is convinced that his lusty comments about the legs and shapes and skin tones and hair color of every woman he meets will make Libby appreciate his manliness even more. The joke, though repeated incessantly throughout the book, never gets old.

Armstrong is satire and fiction at its finest. Crocker has given us a treasure and one that, this reviewer hopes, will be but the beginning of a series of Custer’s adventures in the West. Viva, Armstrong Armstrong! Now, to return to Council Grove, Kansas, and see if Crocker’s new novel has forced the town leaders to change that sign. . . . After all, each only hovers on the edge of reality.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.

Comments