God Bless You, Frank Miller

Frank Miller raged.

He stood naked at the edge of the skyscraper. The streets lay far below him. A frozen explosion of steel and glass burst in flight to the sky over the motionless traffic. The traffic seemed immovable, the steel and glass flowing. The steel and glass had the stillness of one brief moment in battle when thrust meets thrust and the currents are held in a pause more dynamic than motion. The steel and glass glowed, wet with sunrays.

(with apologies to Miss Rand and the writers of the Christian Gospels)

There is no doubting that the attack on the World Trade Centers on September 11, 2001 fundamentally shaped one of the greatest and most innovative artists of the last half century, Frank Miller.

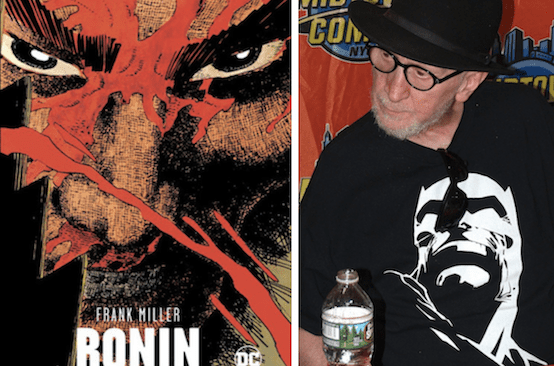

Though his name might not be instantly recognizable to many readers of The American Conservative, his shadow hangs over much of popular culture, enigma though he might be. Films, novels, and television shows—directly and indirectly—reveal daily his vast imprint on American culture. While many book sellers and critics do not consider graphic novels serious literature, his 1986 work, The Dark Knight Returns, has sold over three million copies, making it a continuous best seller since its initial publication. Even Miller himself despises the term “graphic novel,” believing it sound too much like something risqué. Still, there’s no denying its success and importance. Miller believes that writers, artists, and readers should embrace the “graphic novel” for what it is: a comic book, plain and simple.

Frank Miller is to comics and film what Neil Peart is to rock and what Camille Paglia is to academia. He is nothing less than himself. Always and everywhere, he is purely Frank Miller. It seems, he could be nothing other than Frank Miller. If he changes, he can only become even more Frank Miller. On September 11, 2001, however, Frank Miller became more fully Frank Miller.

Those of us not on the political and cultural Left should celebrate him as a radical and unreconstructed individualist, the kind that only North America seems capable of producing in the post-modern world, a man never afraid to voice his views, whether commensurate with the bullying and mindless nightmares of the mob or not.

The Emerging Talent

Born in 1957 to Irish-American Roman Catholics, Miller grew up in Vermont, one of seven children. From about age five, he fell head over heels in love with comics, and his parents encouraged and nurtured this passion. At times, he found his early adult careers on the edge of derailment. Finishing high school because of the advice of his parents, Miller tried his hand at janitorial work, at transporting goods in trucking, and at driving buses. Every boss he had prior to entering the field of comics fired him.

In the late 1970s, as he lost job after job, he began to study with the then-best artist in the comic world, Neal Adams. After working at Gold Key comics and on lesser-known titles at DC, Miller moved to Marvel and soon took over the then nearly-defunct character, Daredevil. Much to the surprise of all at Marvel and in the comic world, Miller wrote what is now considered the definitive Daredevil, an anguished and blind Matt Murdock who regularly seeks the sacrament of Confession, confiding in his parish priest, as he wonders just how far he can fight in the name of vigilante justice. With Miller as writer, Daredevil went from being relatively obscure to being one of Marvel’s finest, most nuanced, and popular comics. After working on his independent cyberpunk comic and hero for DC, Ronin, Miller then moved to Batman. Miller not only revived the then-failing character but, along with Alan Moore and his The Watchman, but revitalized the entire comic industry, then on the edge of bankruptcy.

An avowed gnostic, a Leftist, and a seemingly particular person, Alan Moore soon left the industry in boredom and disgust, but Miller stuck with it. A monumentally determined perfectionist, Miller kept his politics much closer to his chest than had Moore, though his quietly expressed views almost always embraced a kind of Goldwater libertarianism. Trying to improve his writing, Miller also read and studied like mad. Not surprisingly, he has read everything from Dashiell Hammett to Robert Heinlein to Christopher Lasch, and he has studied Japanese and European comic styles. Restless and curious to the nth-degree, he became an amateur anthropologist as he traveled throughout Asia and the Near east, observing everything from cultural norms to speech patterns to the shades of light hitting the landscape.

His reading and traveling, combined with his love of cinema, seeing everything from Hitchcock to Dirty Harry, Miller honed his own art—in drawing and writing—to write modern myth, centering around the hero and anti-hero, around good and evil, and around beauty and chaos.

If understood properly, Miller persuasively argued, heroes bring us back to first principles of “right and wrong.”

“I love heroes, I believe in heroism. I also adore fantasy, and so I’m drawn back to these superheroes,” Miller explained in October 2016. “Their mythology is open to infinite expansion, and the basic myth is irresistible. They got so much right in that first Superman movie, down to the tagline “you’ll believe a man can fly. That’s our job.”

His explicit goal has always been “to do heroic adventures without compromise.” Too much of modern culture, he complains in the vein of Russell Kirk and C. Wright Mills, has become nothing but conformist drivel, with movies, television shows, and comic books serving the public at large as heavy “sedatives.” Instead, we need the Batmans and Dirty Harry’s to bring the “wrath of God” down upon the murderers, rapists, and tyrants of the world. The world desperately needs morality, order, and myth.

With his trademark fedora, open jacket, t-shirt, and scruffy white beard, Miller might look almost as unpleasant as Alan Moore really is. But, watch an interview with Miller and you’ll find he’s about the nicest guy in the world.

Unforgivable

On the tenth anniversary of 911, Miller did something unforgivable to the politically correct mafia as well as to the state of Iran (which condemned him, he proudly reminds us). He published a graphic novel, Holy Terror, in which the bad guys are Islamic fundamentalists. The first release of the then-fledgling company, Legendary Comics, a subsidiary of Legendary Pictures, Holy Terror horrified most of the media, formal and social. In the press release that launched the book, though, Miller’s editor, Bob Schreck wrote: “It has been my extreme pleasure and honor to have worked so closely with Frank for over 20 years now.” The new graphic novel, Holy Terror “finds Frank at the top of his game. A fast paced, biting commentary on our uncertain and volatile times, told with some of the most gut-wrenching, iconic images he’s ever produced.”

Schreck, though, stood affront a tidal wave of epic proportions. Wired called it “one of the most appalling, offensive, and vindictive comics of all time,” a product of “9/11 decadence” a “horror” of America’s “carefully nurtured grievance.” ThinkProgress claimed that Miller was “viciously Islamophobic” and took pleasure in the “sexualization of torture.” Others called it a “mean and ugly book,” “sickening,” a book about “rage-aholics with a limited vocabulary,” “fodder for the Anti-Islam set,” a “revenge fantasy” of a person who has removed himself “from reality,” and a “sloppy, arrogant work by an arrogant bastard.” Even Miller’s hero and mentor, Neal Adams, claimed—without details of how and where—that Miller had allowed his work to consume him, claiming Miller had become “white trash.”

In the year following the book’s publication, Miller unapologetically defended Holy Terror, explaining, rather rationally, “I lived through time when 3,000 of my neighbors were incinerated for no apparent reason. I lived through the chalky, smoky weeks that followed and through the warplanes flying overhead and realized that, much like my character, The Fixer, I found a mission.” Drawing inspiration from the anti-Nazi and anti-Japanese Empire war comics of the 1940s, Miller saw his own work as the equivalent in the war against terror. No doubt, he openly admitted, “I come in with my own very pro-Western-they-attacked-my-city-point of view.” In no way, he continued, did he mean “to be fair or balanced.” Interesting to be sure, Miller had earlier in his career complained that too much in comics was propaganda, not art. “My one attempt at” propaganda, he conceded in the early 1980s, “was a dismal failure.” Asked why, he responded, “It was too preachy.” A quarter of a century later, though, he was ready to try his hand at it.

When asked earlier this year by the London Guardian if he would still defend his views as vented through 2011’s Holy Terror, Miller admitted that the work was, at times, “bloodthirsty beyond belief.” Still, he noted, he would never go “back and start erasing books.” The Guardian took this as an apology, and many in the comic industry and media have since forgiven him.

What was so patently obvious to anyone who knew Frank Miller’s work, however, was that Holy Terror was no more and no less anti-fundamentalist than his other works. His masterpiece, The Dark Knight Returns (1986), attacked Protestant fundamentalism, and his noir series, Sin City (1991-), showed the heinous results of Roman Catholic fundamentalism. His recreation of the Battle of Thermopylae, 300, portrayed the Persians as slavish fundamentalists worshipping a god-king. Though Iran condemned Miller for 300, most critics gave him a pass (and often high praise) for his anti-Evangelical and anti-Catholic fundamentalism. For a billion reasons, though, they found his anti-Islamic fundamentalism unacceptable. Hypocrites all.

God bless you, Frank Miller

As soon as Miller became secure and success in the field of comics by the mid 1980s, he not only nurtured anyone who asked for his help, but he also launched a major and public campaign urging comic companies to pay their writers and artists better upfront as well as in royalties earned. Not only did Miller help resurrect the dying industry in the 1980s, but, since, his example and efforts have led to a flourishing of talents in and around comics and movies.

Combatting the Jerry Falwell and Tipper Gore busybodies of the 1980s, Miller also attacked censorship at every political level, convincingly arguing that with few exceptions, censors never know what they are doing, while their motives are less than pure. They seek power over society as well as governmental and corporate control over family. Time and again, Miller stressed, it is the sole prerogative of the mother and father to censor material for the family, not the job of the state to do so.

Sometimes, Miller takes his mischievousness to untoward levels of poor taste, such as when he plasters the “Approved by the Comics Code Authority” stamp on a sexy, female robot tart in his stories of Lance Blastoff. Generally, though, the humor is more “junior high level” than it is clever satire. Still, there’s a definite humor to it, even when he shocks, simply to shock.

While it’s tempting to love Miller for the enemies he has made—here in the United States and in Iran—it’s far better to praise him for his virtues and his innumerable creations. Through Daredevil, he taught us wisdom; through Batman, he taught us morality; through 300, he taught us fortitude; through Sin City, he taught us struggle; and through Martha Washington, he taught us patriotism. When talking about his own work and its expressions of heroism, he wisely noted that “doing the right thing routinely causes one great difficulties and one has to sacrifice a lot.” This is not just true for his heroes, but for Miller himself.

God bless you, Frank.

Bradley J. Birzer is The American Conservative’s scholar-at-large. He also holds the Russell Amos Kirk Chair in History at Hillsdale College and is the author, most recently, of Russell Kirk: American Conservative.

Comments