Will the Electoral College Survive 2012?

The presidential campaign is almost over, but don’t expect it to end quietly. There’s a good chance the outcome will resemble that of the 2000 election: a late night, hanging chads or their equivalent, and perhaps even a mismatch between the popular and electoral vote.

Mitt Romney leads President Barack Obama among likely voters by 50 percent to 46 percent in the latest Gallup poll. Rasmussen has the race a bit closer at 50 percent to 47 percent. The ABC News/Washington Post poll shows Romney with a slim 49 percent to 48 percent lead, and the RealClearPolitics polling average of likely voters has Romney up by nearly a percentage point.

Yet Obama is faring somewhat better in the battleground states that will decide the race for 270 electoral votes. Polls show him leading in Ohio, Iowa, Wisconsin, and Nevada, among other swing states. He is still slightly ahead in the polling average for New Hampshire, and Romney and Obama are tied in Virginia and Colorado.

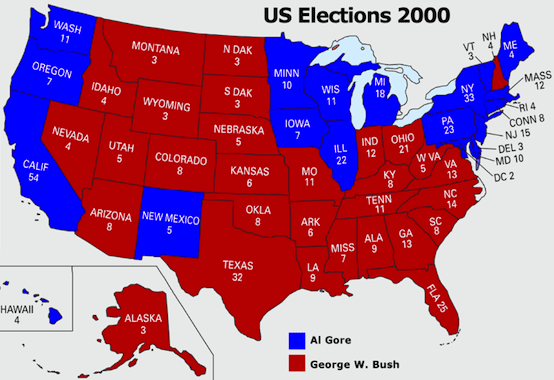

In that sense, this year’s election could be the inverse of 2000: there’s a non-trivial chance the Democrats may lose the popular vote but prevail in the Electoral College. And the contest between George W. Bush and Al Gore a dozen years ago was an important primer on which vote is constitutionally binding. Obama can lose the popular vote and still be reelected.

That this outcome is possible does not make it inevitable, of course. Neither Romney’s national lead nor Obama’s similarly small advantage in the swing states is insurmountable. If Romney holds on to his base vote and late deciders break in sufficient numbers for the challenger, he could win some combination of Wisconsin, New Hampshire, Colorado, and Ohio in addition to the popular vote.

By the same token, if Obama can dissuade enough of the remaining undecideds from voting for Romney—or turn out a higher number of minorities and other Democratic base voters than pollsters like Gallup assume—he can win the popular vote while also denying Romney an electoral majority.

Nevertheless, it’s worth asking whether our current presidential election system could survive two mixed verdicts in the electoral and popular votes in just 12 years. When Bush beat Gore in 2000, as the result of a disputed outcome in Florida, a confirmed popular vote loser hadn’t been elected president since 1888.

Such mismatches have been rare, occurring only four times in our history. Three of the four came in the 19th century when the country was much more accepting of the fact that the popular vote didn’t decide the presidency. But to modern sensibilities, the Electoral College seems anachronistic and undemocratic. The argument for electing the president by straight popular vote—as many Americans have long assumed we do anyway—would likely resonate.

Indeed, Gallup found a year ago that 62 percent of the American people—including a majority of Republicans—would abolish the Electoral College in favor of popular presidential elections. This is consistent with their results from 1967 to 1980. But two things will make repeal difficult: inertia and the need for a constitutional amendment. Even popular amendments are notoriously hard to ratify.

The intensity of anti-Electoral College sentiment spiked among Democrats after 2000. If Obama won a second term in this fashion, many Republicans would become enthusiastic about the idea. This could create the kind of bipartisan movement that makes a constitutional amendment possible.

Then again, we might simply see the parties reverse their positions on the Electoral College based on momentary political convenience. When it looked like the 2000 electoral/popular vote split decision might go the opposite way, the Bush campaign was prepared to rally for the election of the popular winner while team Gore defended the legitimacy of the constitutional system.

But the longer the country remains evenly divided between two parties, the greater the chances for a narrow popular vote winner to lose. There were close calls in 1976 and 2004, as well a serious argument to be made that Richard Nixon had actually bested John F. Kennedy in the popular vote. If this becomes common, the push to get rid of the Electoral College will gain strength.

Its abolition would just be the latest step away from the idea of a federal republic toward the notion that the narrowest plurality of Americans should get whatever it wants from government. What we really have is the composite of 50 state elections rather than a single national election. No one found this practice remotely controversial until Hillary Clinton lost the 2008 Democratic nomination to Obama—and it took fairly creative accounting to crown Clinton the popular vote winner in that race.

Florida-like recounts would be more common, not less, because both parties would scour the country for irregularities to erase small popular-vote margins. Gore’s 540,000-vote edge over Bush nationally was as much within the margin of error as Bush’s 537-vote lead in Florida.

In fact, the Electoral College has helped make many solid but unspectacular popular vote performances appear far more decisive. Think George Bush in 1988, Bill Clinton in 1992 and 1996, and even Obama in 2008. A 53 percent majority seems more impressive when it comes with 300-plus electoral votes. More often than not, the result serves to increase the legitimacy of the popular-vote outcome.

Alas, enough divergences from the trend will likely make us a nation of Electoral College dropouts. Nuts to that. May the best electoral vote-getter win.

W. James Antle III is editor of the Daily Caller News Foundation and a contributing editor to The American Conservative. Follow him on Twitter.

Comments