Where is Real Statesmanship When We Need it Most?

The view that America is the indispensable leader in efforts to make a better world has long been so dominant in American foreign policy thinking as to seem axiomatic. Much of the current hostility to the Donald Trump presidency originated within the foreign policy networks that connect government, think tanks, media, and academia. Trump’s assertions during the presidential campaign that America should play a more limited, non-interventionist role and put “America First” created profound discomfort. Though his real intentions as president are still unclear, his penchant for repeatedly violating conventions of speech and action has inflamed the passions of the national elites, particularly the foreign policy establishment.

So intense and confrontational is the hostility to Trump that it amounts to a constitutional crisis. It generates the potential for further political turbulence that might have devastating consequences. The danger is particularly acute in the area of foreign affairs, where decisions of far-reaching importance relating to Russia, North Korea, China, and other countries could fall prey to passion, short-sightedness, and recklessness. This is an alarming prospect, for sound leadership in international relations demands the very opposite—calm reflection, long views, and caution.

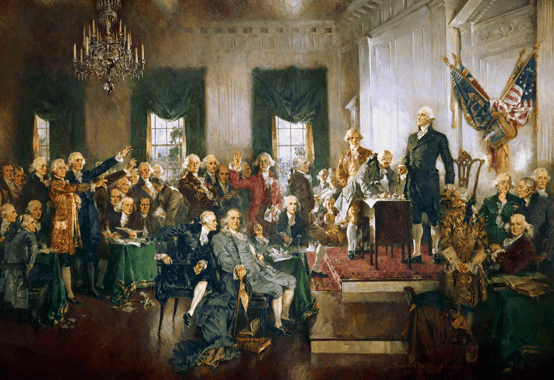

To recover their moral and intellectual bearings, Americans need to pull back from the demagoguery and turmoil of the moment. They would do well to remind themselves of an older model of debate and decision-making. That model, which should be for them a default setting, is today virtually ignored—the U.S. Constitution. Here the primary source of wisdom is not constitutional prescriptions like the congressional prerogative to declare war or the Senate’s treaty power, as important as they are. These institutional and procedural specifics are but the tip of an iceberg. What needs to be better understood and brought to bear on current problems is that the Constitution is the political expression of a general view of human nature and society. It embodies an entire American ethos, of which a certain view of how to make political decisions is but a part. The Framers’ way of approaching political problems and life generally was not only realistic and far-sighted but morally astute.

Much more attention ought to be paid to the fact that prominent general assumptions and features of the Constitution, though not explicitly connected to international relations, carry important and wide-ranging implications for foreign as well as domestic affairs. Specifically, they assume a notion of statesmanship.

It used to be generally recognized that, especially in foreign affairs, inferior leadership can have disastrous consequences. There the need for circumspection and restraint is acute. Run-of-the-mill politicians may be prone to narrow-mindedness, demagoguery, and carelessness, but statesmen have the vision and the character to rise above the quarrels and opinions of the moment. They have a historical frame of reference and critical distance to their own time. They recognize dangers and opportunities not apparent to lesser men, and they have a capacity for audacious leadership. When necessary to advance the common good, they are willing to go against prevalent opinion and even to risk their political careers. Statesmen too will have human flaws, but they have as their models some of the most admirable members of the human race. A desire to move people with this kind of potential for leadership into influential positions was integral to the constitutional design of the American Framers.

Looking for modern Americans who exemplify statesmanlike qualities, one might turn to the end of the Second World War and the Cold War. Action taken by Senator Robert A. Taft after the defeat of Nazi Germany may illustrate the willingness to risk media censure or other unpopularity. It was John F. Kennedy who, in his book Profiles in Courage, pointed admiringly to Taft, who despite clamoring for vengeance opposed the plan to accuse the German leaders of war crimes before specially constituted courts and according to specially designed laws. The idea of applying ex post facto laws was, Taft insisted, repugnant to the American legal tradition with its deep roots in British and Western jurisprudence. Not even the vileness of the Nazi leadership could excuse legalistic posturing. At a time of growing anxiety about the Soviet Union and world communism George Kennan exemplified another side of statesmanship by providing both a sense of direction and a calming, steadying influence, which were made possible by a rare combination of intellectual power, historical acumen, experience, and realism. Later in the Cold War when fear of the Soviet Union and communism still ran deep in America, one example of the boldness that statesmanship sometimes requires stands out. Only an American leader of unusual foresight, daring, and willpower could have conceived and acted on the possibility of an opening to China, which carried great political risks.

At the same time that the Framers sought to promote a leadership elite, nothing seemed to them more important than to limit, divide, and decentralize power. Even the best of men are prone to overreach. The Framers’ deep distrust of human nature derived from biblical and classical sources and historical observation. Moral and prudential restraint on human depravity had to be imposed first of all by individuals on themselves, but constitutional and other external checks, individuals and institutions exercising checks on other individuals and institutions, were a necessary part of the effort to tame man’s baser passions.

Realistic though they were about human weaknesses, the Framers sought to promote the common good. They looked in particular to the republics of Greece and Rome for models as well as warnings. Without republican virtue—self-discipline, modesty, and devotion to the public things—their constitutional system could not work. They wanted to increase the likelihood that people of wisdom, moral character, and the right experience—potential statesmen—would have a disproportionate influence over policy. For generations of Americans, George Washington stood out as the quintessential republican leader.

Though the Framers favored a system of popular consent, they dreaded demagoguery and short-sightedness. They feared a majority agitated by merely partisan interest, what they called a “majority faction.” Such rule would endanger minority interests and threaten the general welfare. A representative system should, in the words of James Madison, “refine and enlarge the public views.” The Senate, the Electoral College, and the Supreme Court illustrated particularly well the effort to promote “the deliberate sense” of the people. The Constitution was to protect the better self of the American people against bouts of ignorance, intoxication, or fear.

Directly relevant to foreign policy is the Framers’ deep concern about the tendency of the powerful to want to lord it over others and to behave arbitrarily and ruthlessly. The inclination of the strong to consider themselves always right is at once prominent and dangerous. The weak need to be respected and protected. Though self-restraint and modesty are of the essence of republican leadership, all power has to be subject to sturdy institutional checks.

Genuinely to aspire to serving the common good is not the same as to know just what that good is in particular circumstances. Life is complex and the facts rarely clear. Statesmen will be predisposed to recognize the interests of different groups and to compromise. War may become unavoidable, but good leaders are predisposed to defuse conflict. Nothing could be more antithetical to America’s constitutional ethos than to demand of opponents that they surrender unconditionally.

Statesmen must forever contend with people incapable of a balanced, many-faceted, and historically informed view of the world: conceited ideologues, nationalist yahoos, self-satisfied pseudo-moralists, ravenous investors, and other partisans. Their disparagement or demonization of opponents is inherently conducive to conflict. Only their side has legitimacy. When Vladimir Putin invaded Crimea mere partisans viewed it as an act of brutal aggression against a foreign country, no matter that since the fall of the Soviet Union the United States and NATO have pushed more and more deeply into the old Russian sphere of interest, in effect pursuing a policy of encirclement. A person of less partisan outlook will recognize that Russia has historical, cultural, and geopolitical reasons to think that it has legitimate interests in Ukraine, especially Crimea, and that it is pushing back against provocation. What seems unacceptable to one side may seem rightful or even imperative to the other.

Because of the propensity of the strong to run roughshod over others, the Framers of the U.S. Constitution favored procedures and institutions that forced restraint and mitigated willfulness. They put a premium on settling disputes by give-and-take. They shunned unilateral actions, such as by simple majority vote. Their system would yield strong and enduring decisions only when a fairly broad working consensus could be achieved. Legislation passed narrowly and over intense opposition—the adoption of Obamacare comes to mind—would be unstable and a source of dissension.

♦♦♦

To summarize the relevance of the American constitutional ethos for foreign policy, nothing could be more germane than that this ethos is, first and foremost, a strong disposition to self-control, deliberation, and compromise. It abhors autonomous, unrestrained power. Power is a possible source of ruthlessness and arrogance and must be limited and decentralized. Marked by modesty and humility, the spirit of American republicanism is inimical to arrogance and conceit. That the strong are often wrong and that the weak have legitimate interests are but two of the reasons for seeking compromise and common ground.

The post-9/11 decision to invade Iraq surely will stand out as a prime example in the 21st century of passions of the moment, shoddy thinking, and cynical manipulation robbing American power of restraint, deliberation, and caution. Decisions of great magnitude fell to a president who had little relevant education, experience, or familiarity with the world that could have protected him against being swept up in the agitation for attacking Iraq, which had nothing to do with the 9/11 attacks.

Some will object to these arguments that America is exceptional by virtue of its universal values and that the world needs and craves American leadership. In this view, since American power is a force for good, it does not need the strict limits that the Framers imposed. These limits are seen, in fact, as obstacles to the efficient use of virtuous American power. What is desirable today is not self-restraint, willingness to compromise, and checks on the ability to wage war. No, what is needed now is great “energy” in the executive.

People who oppose this attempt to subvert constitutional checks on power and would like to see these checks restored may at the same time plausibly argue that America has moved so far from character traits of self-control and modesty that the Framers’ advocacy of deliberation and seeking common ground is anachronistic. What is desirable, to return to the Constitution, is not, at least not for the foreseeable future, practically possible. People strongly attracted to constitutionalism may also believe that in a political environment of increasingly blatant partisanship, crude and inflammatory ideology, and egregious demagoguery, the old-fashioned preference for debate and compromise will only play into the hands of the most pernicious and ruthless among the established elites. The only way to deal with such partisans and to give constitutionalism a chance to survive is to confront and defeat them.

The reasons for deemphasizing compromise and deliberation and for welcoming or accepting strong presidential leadership can thus have widely divergent motives, but they all illustrate the erosion of the moral and cultural supports for American constitutionalism. The old constitutional temperament is up against historical circumstances more conducive to rabble-rousing and authoritarian leadership—precisely the dangers that the Framers feared.

Hence we face a paradox. The U.S. Constitution teaches urgent lessons about leadership, and the American constitutional temperament is highly relevant to foreign affairs. Yet today’s historical circumstances seem to conspire against this temperament. What, then, of the prospects for statesmanship?

If the old-fashioned American ethos of leadership has dissipated because its civilizational supports have eroded, only a general revitalization of old moral and cultural traditions or the emergence of some new version of the same could generate a general resurgence of the spirit of statesmanship. Since there are few signs that this kind of renewal of civilization might emerge in the foreseeable future, the question becomes whether individual leaders with a potential for statesmanship might arise in the current deteriorated moral, cultural, and political climate. Could such persons create breathing room for even a partial recovery of constitutionalism?

In view of the sad state of American politics, some readers may believe that the kind of statesmanship described here must be a kind of political luxury, requiring fair-weather conditions. But true statesmanship is characterized by the kind of uncompromising realism that the Framers exemplified, and its sense of direction is applicable to any and all circumstances.

Thinking about specific practical measures that might constitute a statesmanlike agenda today would require an assessment not only of what is desirable but of what is possible, a very large subject. A central general point is that genuine statesmanship is animated by a distinctive ethos that tends to move societies towards respectful relations, domestically or internationally. To the extent that leaders share this ethos, they will tend to take each other’s concerns into account. This is not to deny that they will often have competing objectives or that leaders of different countries must adjust their domestic and international agendas to their special circumstances. They have different and potentially conflicting interests. Leaders of countries must attend to military and economic imperatives. But statesmen realize that their counterparts in other countries must do the same, and they recognize the need for reasonable accommodation among contending parties. Thus does the spirit of statesmanship tend to moderate inevitable tensions and encourage negotiation.

At the very core of this ethos is an acute awareness of the baser inclinations of the human self and the need to control them. For genuine statesmen this need is not an abstract general observation about human nature but something deeply and personally felt. The moral realism in question is indistinguishable from a spirit of self-examination and self-limitation and a wish to act for the common good, an aspiration that was central to American republicanism. Integral to the same ethos of statesmanship are modesty, circumspection, and critical distance from the historical moment. Because the inspiring spirit is always the same, the diverse practical measures of statesmen tend to move their countries in the direction of peaceful coexistence.

If this is a summary of the moral and intellectual temper and practical import of statesmanship, what, more specifically, might comprise statesmanship in America today? It can be argued that the U.S. Constitution has been so enfeebled as to be barely intact and that America is facing something like a moral-spiritual collapse. The forces that foster and benefit from this state of affairs are at the same time deeply entrenched. There is, however, in genuine statesmanship no inclination to retreat from difficult challenges. It has nothing to do with sanctimonious Platonic disdain for debased politics or with fruitless nostalgia for something lost, but neither does it resort to cynical expediency. Though marked by a strong sense of purpose, statesmanship is eminently pragmatic. Whatever the circumstances, it wants to make the best of them. Although it has no choice but to adjust to decadence, its purpose in doing so is not to yield to but to outmaneuver the destructive forces, for example, by using their methods against them. Statesmanship has to be at once creative and robust. To withstand the inevitably fierce counteractions of a threatened reigning establishment, it must be tough and skilled in the use of power. In an era in which public opinion and opinion polls are an important measure of political legitimacy it must somehow maintain popular support. Paradoxical as it may seem, one of the chief requirements of statesmanship in today’s America must be to adapt to a media-centered and highly demagogic public discourse but to turn it to advantage by using similarly simplified but redirected rhetoric. As a readiness to act in any and all circumstances, statesmanship may today have to assume an unfamiliar form. Guardians of conventional respectability may find its audaciousness disturbingly unorthodox.

To look today to the U.S. Congress for imaginative, courageous leadership seems fruitless. Its leaders appear incapable of thinking creatively about how to address deep-seated problems. Members of Congress collectively reflect a deteriorating and fragmenting society. Rather than transcending the usual posturing and demagoguery designed to avoid media censure and ensure reelection, the leaders of Congress appear content to shore up a crumbling status quo.

It is too early to assess the extent to which Donald Trump might represent statesmanship for our time. He certainly does not cling to the dilapidated status quo. That he sends defenders of the established order into paroxysms of outrage is not dispositive, although it does indicate that his opponents perceive him as posing a real threat. That is certainly how those who elected him viewed him. Only very deep resentment in the American people and Trump’s special rapport with a large segment of voters could account for the rise to the presidency of this political neophyte with much dubious personal baggage. Many Americans, acting on gut-feeling rather than reflection, seem to have concluded that beggars cannot be choosers.

Not enough attention has been paid to how truly remarkable it is that Donald Trump was elected president. His winning the nomination of a reluctant party and then winning the presidential election was nothing short of miraculous. Political scientists and seasoned political journalists will tell you how utterly difficult it is for an aspiring politician to reach the presidency. Not only did Trump come from the outside, he had to run against experienced, well-organized, and well-funded competitors. He was also up against virtually monolithic media hostility. It says something about the viability, creativity, and timeliness of Donald Trump that this supposedly vulgar upstart was able to outmaneuver—everybody.

This blustering and almost roguish amateur politician who keeps violating conventional norms might appear the opposite of statesmanlike. Is it, then, out of the question that his high-wire act might be a form of statesmanship adjusted to a fraught moment in American history? Snobs and guardians of the status quo will of course scorn such an idea. Yet it is conceivable that the brashly self-confident style of Trump, so different from the formulaic conduct and speech of other politicians, might be a way of advancing a change agenda in an increasingly debauched and dully predictable political culture.

The upholders of conventional respectability should ponder the survivability of a leader who genuinely wants to challenge the established order but who also measures up to their refined standards of conduct. Was their ideal candidate on offer in the latest presidential election? If so, how well did he or she do? Trump’s braggadocio, hyperbole, and outsized ego offend traditional Christian sensibilities especially, but, given the magnitude of America’s problems and the strength of the opposition to real change, would Americans have preferred a more unassuming, low-key leader? Trump’s strong rapport with a core group of voters may have something to do with a subconscious identification with this caricature of a typically American personality, a larger-than-life embodiment of their own aspirations.

Establishment figures in politics and the media have been aghast at Donald Trump’s rank demagoguery. Their criticisms have far from always been unjustified, but the conceit and nearsightedness of these arbiters of respectability has blinded them to how selective their indignation has been and to the fact that demagoguery, though of a different, approved kind, has long been an integral and expanding part of American political and media discourse. The established order with its main media outlets both fosters and takes advantage of a deteriorated political and journalistic culture. Trump infuriates those normally in charge of the view of the world and of public opinion by simply violating their prescribed rules and often beating them at their own game.

Many of Trump’s supporters assume, mostly on good grounds, that much of his rhetorical bluster is merely conversational hyperbole or an act. His impetuous way of countering criticisms and his propensity for sweeping, off-the-cuff assertions seem to them a refreshing contrast to the scripted speech and conduct of other politicians.

Trump’s stated general views do in important ways harken back to a more traditional ethos in American politics. He defends an old-fashioned sense of American national identity—“our country”—and opposes the kind of national self-effacement that results from open borders, politically correct multiculturalism, and other cultural radicalism. He wants to protect American workers against trade arrangements that he deems unfair. He has made the need for national sovereignty, that of the United States and of other countries, a central theme. His advocacy during the election campaign of limiting America’s involvement in the world comported, if allowance is made for America’s circumstances in the 21st century, with the disposition of George Washington and most of his American contemporaries. Trump’s stated desire to make more room for negotiation and compromise with foreign competitors points in the same direction.

♦♦♦

If there are thus elements in the Trump presidency that suggest at least the potential for a new kind of American statesmanship, other elements call that potential into question. Statesmanship includes an inclination to be self-critical, to check the impulse of the moment, and to have a sense of distance to the events of the day. By contrast, Trump often exhibits impulsiveness and a preoccupation with the concerns of the moment rather than calm reflection. Only an intuition of exceptional quickness and soundness might protect such a man from big mistakes.

In foreign affairs Trump ran on a preference for negotiation over confrontation, but in office he has been prone to bellicose rhetoric, assertive military action, and impatience with diplomacy. As president he has fallen back into and even reinforced the habits of the more hawkish members of the foreign policy establishment. He and his aides have brought into the administration many figures who represent just the kind of interventionism and push for global hegemony that he criticized during the presidential campaign. The president appears to lack the knowledge and intellectual independence to resist assertions of power from that quarter. The extent of the militarization of the upper echelons of his administration has contributed to an impression of foreign policy assertiveness and even militarism.

Similarly, in the economic field the president has given great influence to Wall Street, a power center that he attacked during the campaign. This suggests that here as in other areas he has only a vague idea of who are and who are not his allies in pursuing his stated larger objectives. A more worrisome explanation for seemingly paradoxical appointments is that he is more closely tied to the money power than he let on during the campaign.

It could be argued that Trump is simply looking for talent wherever he can find it. His fondness for generals may reflect a fundamental disdain for the creatures of the swamp and a preference for what he takes to be disciplined people who are used to serving their country and acting in tough circumstances. His alliance with Wall Street oligarchs and other big money people could conceivably exemplify a strategy of keeping his enemies closer than his friends. He may have decided that confronting a supremely powerful element in American society would not only be pointless but doom his presidency; only by reassuring at least parts of this element could he hope to gain some freedom of movement. There is another, perhaps more likely, explanation for his paradoxical appointments and his apparent pragmatism: that they are, for the most part, the result of poorly integrated, even contradictory beliefs, and of naiveté about the real nature of America’s reigning elite.

Trump supporters disgusted with the established order may argue that there is no such thing as a flawless political leader. All leaders are mixtures of good and bad. One might add that debased, fragmenting societies tend to produce leaders who are prone to strong action but are also lacking in subtlety and caution. Whatever the case with Donald Trump, major shortcomings in a president of the United States can have disastrous consequences, especially in foreign affairs. That the U.S. Congress has abdicated to the executive its authority to decide on war or peace is but the most striking example of an abandonment of constitutional restraint that could lead to catastrophe.

Real statesmanship is a crowning achievement of civilization. We recognize it precisely because it is out of the ordinary. America’s current historical circumstances cry out for statesmanship adapted to the country’s precarious moral-spiritual, cultural, and political condition. We had better not be too quick deciding what statesmanlike daring and vision might look like in today’s America. Donald Trump has thrown a big monkey wrench into a flailing and yet intractable system dominated by confused, corrupt, and conceited leaders. He has created an opportunity for changing direction. Whether he has the moral compass, the understanding, the temperament, and the capacity for statesmanship and whether the American people are capable of the needed change remains to be seen. The alternative to major reform is further deterioration and, in foreign affairs, more wars and provocations that could at any time trigger a cataclysm.

Claes G. Ryn is professor of politics and founding director of the new Center for the Study of Statesmanship at The Catholic University of America. He is honorary professor at Beijing Normal University. His many books include America the Virtuous and the novel A Desperate Man.

Comments