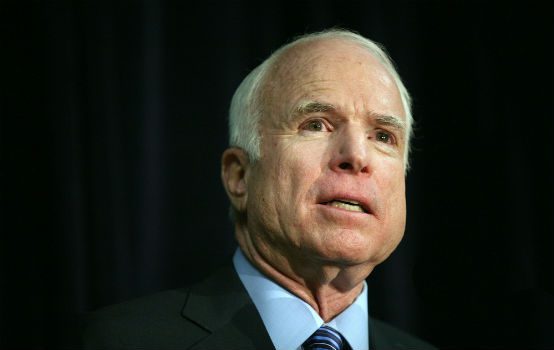

When John McCain Was Right

Unlike many political journalists, my first John McCain story predates my arrival in Washington. The Arizona senator came to deliver the commencement address at my college, before he was a presidential candidate but after he began earning liberal plaudits with his embrace of campaign finance reform. As one of the few Republicans on campus known to the administration, I was part of a small delegation to welcome him at the airport.

McCain traveled without any staff. When we took him to the McDonald’s drive-thru for a cup of coffee, he pulled out a denim wallet and insisted on paying himself. Our next stop was a supermarket to pick up some sunscreen, as he had already had a bout with skin cancer. None of the shoppers appeared to recognize him.

“Not many C-SPAN viewers here, senator,” I remarked. “Yes,” concurred a successful alumnus accompanying us. “No one has recognized either of us.” McCain looked at me and rolled his eyes.

We saw much of McCain’s funny, charming, and unpretentious side. Only once did we witness his famous anger: he complained during the car ride that Pete Wilson, then the governor of California, was ruining the Republican Party by mixing racism with “left-wing social policy”—the pro-choice pol had revived a flagging reelection bid a few years earlier by veering right on immigration. I declined to tell McCain I had purchased my copy of Peter Brimelow’s Alien Nation at the university bookstore, a tip I apparently should have passed on to Larry Kudlow.

It was vintage McCain: approachable and recognizably human in a way that most career politicians are not, fun to cover as a journalist, capable of the kind of deep bipartisan friendships that were once common in the nation’s capital and now seem less so. But McCain didn’t always extend the same charity towards those to his right, or especially to outspoken critics of the wars he wanted to wage.

McCain’s undeniable bravery as a POW during the Vietnam war—his steadfast refusal to accept an early return home proved one can indeed be a hero while captured—made him a far more effective advocate for interventionism than Dick Cheney, who had “other priorities” at the time, or George W. Bush, much less the various laptop bombardiers who were blogging their way to Baghdad.

Yet when the country followed McCain’s foreign policy advice after the Cold War, the results were often calamitous. In his last book, he finally admitted as much about the disaster that unfolded in Iraq.

“The principal reason for invading Iraq, that Saddam had WMD, was wrong,” McCain wrote with his co-author Mark Salter. “The war, with its cost in lives and treasure and security, can’t be judged as anything other than a mistake, a very serious one, and I have to accept my share of the blame for it.”

For years after all of this became obvious, McCain didn’t in fact accept very much in the way of blame for it. Instead he heaped scorn on political rivals who opposed the decision to invade and attributed many of war’s dire consequences, including the emergence of ISIS, to those who wanted to cut our losses and withdraw. McCain also took credit for his prescience on the troop surge, which only “worked” insofar as it facilitated the withdrawal he described as a “colossal failure.”

“Lindsey Graham and John McCain were right,” McCain said of Iraq just four years ago.

None of this would be worth rehashing at the time of his death but for one reason: McCain wanted to concede that Iraq was a mistake while applying the same regime change logic to Libya, Iran, and Syria. Here he was not a maverick—the bulk of the bipartisan political class and Beltway national security apparatus believes the same thing.

Earlier in his career, McCain was far more skeptical about the use of military force. He spoke out against a closely allied president of his own party, Ronald Reagan, on the dispatching of U.S. troops to Lebanon and continued to do so after the bombing of the Marine barracks in Beirut. In the early 1990s, he opposed repeating this error in Bosnia, arguing that we shouldn’t take sides in a foreign civil war because of the difficulty in “distinguishing between friend and foe.” He was against humanitarian interventions in Somalia and Haiti.

“I don’t think our vital national security interests are at stake,” McCain said in 1994. “In Haiti, there is a military government we don’t like. But there are other governments around the world that aren’t democratic that we don’t like. Are we supposed to invade those countries, too?”

It doesn’t lessen McCain’s legacy to say that he was more right in 1994 than he was in his later years, when he argued against the idea of conflicts between American interests and ideals without articulating any obvious limiting principle. He remained a consistent voice against torture throughout, however.

An unfair criticism of McCain is that his choice of Sarah Palin to be his 2008 running mate encouraged the lower-brow forms of populism the senator would later lament, culminating in President Trump. While Palin had many flaws, the truth was the opposite—there needed to be more creative efforts by responsible Republican leaders to engage the base’s anger, not less. McCain’s inability to do so on issues like immigration, foreshadowed in our ride from the airport all those years ago, did far more to create the conditions for Trump than Palin.

The outpouring of grief that has followed McCain’s passing owes as much to the sense that a better political climate is being buried with him as it does to his military service. Some on the right now see McCain’s virtues—civility, graciousness in defeat, policing the Republican ranks against racial intolerance—as vices. The left last year vacillated between celebrating McCain and vilifying him in the cruelest imaginable terms based on whatever vote he was casting on Obamacare at the moment.

Let us emulate John McCain’s contributions to peace at home and chart a different course abroad.

W. James Antle III is politics editor of the Washington Examiner and author of Devouring Freedom: Can Big Government Ever Be Stopped?

Comments