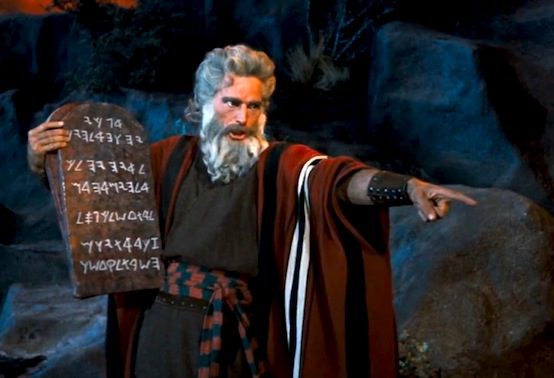

Was Moses the First American?

Indulging in what seems to be its regional pastime, Texans are fighting about schoolbooks again. While previous debates centered on science instruction, this time it’s proposed history texts under scrutiny (I blogged about the curriculum standards they’re supposed to meet here). At a hearing last week, books under review by the state Board of Education were blasted for saying too many nice things about Hillary Clinton, not enough nice things about Reagan, and too much about Moses altogether. In widely-reported testimony, the SMU historian Kathleen Wellman argued that the books treat Moses as an honorary founding father—so much so that “I believe students will believe Moses was the first American.”

I haven’t seen the proposed texts, so Wellman’s criticisms may be justified. But non-academics should be aware one of the most exciting movements in intellectual history in the last decade or so has discovered the extraordinary prevalence of “Hebraic” rhetoric and symbolism in during the revolution and in the early republic.

Needless to say, Moses was not the first American. As Eran Shalev shows in his fine survey American Zion, however, early Americans were remarkably likely to think that their political struggles followed a pattern set by the Biblical Israelites. Washington, for example, was routinely identified as a modern Joshua. And the Union was often compared to federal arrangements among the Hebrew tribes.

The discourse of Hebrew republicanism is an important supplement to more familiar stories about the influence of Locke or the civic republicanism inherited from the Renaissance. At the same time, it’s hard to teach to beginners.

It’s important to avoid reductive arguments that America has a theological foundation. As far as we can tell, Hebraic models were more common in popular discourse than in elite deliberation. So while they played an important role in the public justification of political decisions and institutions, they had little direct influence on their design. And the republican interpretations of scripture on which the patriots relied in the 1770s and ’80s were not only selective, but also fairly novel. As recently as the 1750s, American clergy and laymen had usually argued that the Davidic monarchy was God’s paradigm of good government.

On the other hand, the politics of the revolution and early republic really were infused with Biblical rhetoric and examples. Neglect of this fact promotes the more fashionable dogma that the America revolution and constitutions were products of a secular society.

Textbook writers are thus in a bit of a pickle. Lacking the space to address complicated topics in-detail, it’s almost unavoidable that they traffic in simplifications. Perhaps the Texas books err on the side of evangelical conservatives by making the American founding more religious than it really was. But plenty of history writing makes the opposite error, stressing a few prominent skeptics at the expense of a richly Biblical political culture.

Samuel Goldman’s work has appeared in The New Criterion, The Wall Street Journal, and Maximumrocknroll.

Comments