The Show That Captured Our Post-Cold War Anxiety

Lost in the endless Game of Thrones updates and water cooler recaps, the television world recently suffered a quiet loss. The spy-thriller Counterpart has been canceled after only two seasons.

Nobody seems to care. Probably because nobody watches the Starz channel, where it lived out its short life. That’s a shame. Counterpart was the smartest show on television and a careful examination of what managerial liberalism does to the human soul.

Essentially an East Berlin versus West Berlin spy thriller with a sci-fi twist, Counterpart owes more to Dostoevsky than to any current genre tropes. Essentially the two Berlins reside in alternate dimensions. The storyline, developed by show creator Justin Marks, follows rival spy agencies that protect this secret. The two worlds are filled with the same people, so everyone has a “counterpart” on the other side. It’s a clever political allegory that gets to the heart of our age of anxiety.

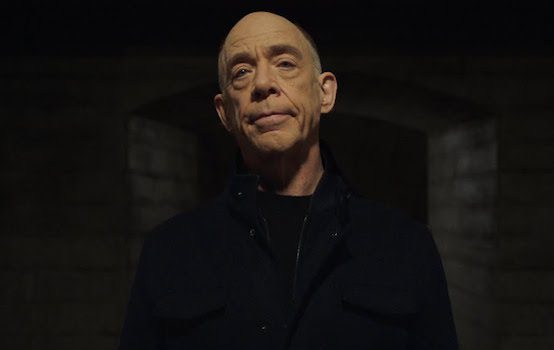

Howard Silk, played by J.K. Simmons, is an American bureaucrat in Berlin. Mild and soft-spoken, he works at a mysterious global organization where everyone uses technology from the 1980s. Howard spends his days deciphering codes with no idea what they’re used for. Then Howard’s wife, played by Olivia Williams, is struck by a car. She falls into a coma. The leader of the secretive Strategy Group contacts Howard, and he’s brought to a holding cell where a prisoner with a hood over his head sits at a table. The hood is removed and it’s Howard, his exact double. Except this other Howard is cynical and tough, everything that our meek bureaucrat is not. Simmons’ performance as the two is reason alone to watch the show.

At one point, according to Counterpart, there was just our single world. Then in the late 1980s, at the exact moment the Cold War ended, everything duplicated, creating two worlds identical in every way. Yet day by day, the realms grew different, and at one point, the other world suffered a pandemic that killed off half the population. Now that world blames ours. The other Howard has crossed over to protect the meek Howard’s wife. She is also a spy and has lied to her husband about her job for years. The car crash was an assassination attempt. This sets up the major questions that drive the story, including, above all, why the two Howards are so different.

Counterpart confronts the viewer with a profound question: why might a single life produce radically different people? The two Howards vary only because they made divergent choices over the last 20 years. The meek Howard has always suspected that his wife had a secret, but never confronted her. The tough Howard confronted her, but that led to a bitter divorce. The meek Howard’s career is a dead end, so he’s engaged himself with hobbies and friends. The tough Howard had no time for anyone or anything other than his career and is hated by everyone. The tough Howard goes on spy missions while scoffing at the other Howard’s small joys, echoing Versilov from Dostoevsky’s A Raw Youth: “Heroism is superior to any happiness whatsoever.” The meek Howard insists that he still loves his wife despite finding out their life was predicated on a lie. His affirmation echoes Alyosha from Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov who says that we must “love [life] before finding reasons why; without logic.”

The show forces us to ask which Howard is truly better, and taps into the great anxiety that accompanies freedom: maybe we’ve chosen wrong. It deals with deeply human issues, but by placing them within the context of a cold war that began at the end of the actual Cold War, it takes on a subtle but distinct political character.

Counterpart suggests that our culture never properly responded to the end of the conflict with the Soviet Union. Communism was defeated under the banner of freedom, but what does freedom look like without its ideological foe? Counterpart is filled with anxious people who are faced with numerous choices and absolutely no moral criteria by which to judge themselves. While the show examines universal human struggles, it also reveals our culture’s conception of the self. Howard doesn’t just struggle with choices; he is defined by them. He is an American living abroad in Germany with no discernible religion who is married to a British woman and works for an international agency. None of these things matter—or rather, the show treats them as if they do not matter. This is the type of freedom that gets promulgated today: to become a rootless cosmopolitan, to be liberated from everything that is not chosen.

The two Howards look at each other with suspicion because neither can say for certain which has taken the correct path. For example, meek Howard’s wife had a miscarriage while tough Howard is a father, which suddenly makes him more than just an accumulation of choices. The unchosen distinction provides a standard that nourishes freedom into something valuable.

Counterpart’s second season moves from an examination of Howard to an examination of how the two worlds began. It’s a stunning indictment of our technocratic elite, showing what happens when we have managers instead of leaders. We see a group of controllers try to use the two worlds as an experiment, treating humans as if they’re just the means to some utopia. Pitted against them is the original creator of the worlds who is something like a Hobbes, De Maistre, or Schmitt, arguing that the doppelgangers are natural enemies.

The show wraps up the main story nicely, but ends on a cliffhanger. An ominous disaster strikes in the closing scene. The series creator has announced that, despite attempts to find the show a home on another network, there will be no third season. This unresolved ending fits well. In a manner, Counterpart is about the uncertainty of our current conception of what it means to be human. Are we just ghosts overburdened with consumerist choices? Are we just raw material to be shaped by technocrats? Are we barely suppressed monsters always one choice away from savagery? Or is there another way?

James McElroy is a New York City-based novelist and essayist, who also works in finance.

Comments