The Reagan Democrats’ Big Coming Out Party

After Donald Trump’s upset victory in 2016, Dan Balz of the Washington Post referred to some Trump supporters as “a 21st century version of what once were called Reagan Democrats.”

When Ronald Reagan walloped Jimmy Carter in the 1980 presidential election, political experts “discovered” those voters for the first time: traditionally Democratic, working-class whites in Northern industrial states whose swing to Reagan blew open what had looked like a close election.

I could have told them about the Reagan Democrats months earlier, because I helped organize their coming out party. It took place on March 26, 1980, at the American Serb Hall on Milwaukee’s Southwest Side.

As chair of Reagan’s 1976 and 1980 campaigns in Wisconsin’s old 4th Congressional District, which covered the southern half of Milwaukee County, I was convinced this traditional Democratic stronghold was ready to respond to Reagan.

I had a drug store in West Allis, a predominantly Democratic blue-collar suburb, and dealt every day with the people who eventually became the Reagan Democrats. They were plumbers and workers at factories like Allis-Chalmers and Kearney and Trecker. They tended to be very patriotic. Many had served in the military. They were hunters and liked to fish. They drove pickups, something country club Republicans in Milwaukee never did.

Previous Republican presidential campaigns had been reluctant to reach out directly to these voters. But as far back as Richard Nixon’s successful races, I knew that a GOP candidate speaking at Serb Hall, where no Republican office-seeker had ever tread, would have a tremendous impact on southern Milwaukee County.

“Serb Hall,” former vice president Hubert Humphrey said in 1972. “If these walls could talk, what stories they could tell of the great Democrats who have campaigned here.”

When Reagan challenged President Gerald Ford for the 1976 GOP nomination, we fought an uphill battle at the local level. Reagan’s national campaign was financially strapped and couldn’t give us any money. The state Republican leadership was locked up for Ford: they ran around with exclusive golf club memberships and sat on the symphony board.

In ’76, we had Serb Hall rented, but John Sears and Charlie Black, who ran Reagan’s national campaign, were convinced their man was going to lose the Wisconsin primary two-to-one. At the last minute, I had to cancel.

Ford did win the primary, but Reagan biographer Craig Shirley would point out three decades later that “in 1976, almost all the states Reagan won over Ford were with the help of Democrats crossing over to vote for him. Reagan spoke to these urban, ethnic Democrats in a way that no other politician had since JFK. Restless Democrats in Wisconsin and elsewhere were ripe for Reagan’s picking.”

Two years later Lee Dreyfus’s successful campaign for governor reached many of those “‘small-c conservatives” we saw as future Reagan voters. Every Democrat who voted for Dreyfus had shown a willingness to switch for the right Republican, and I knew Reagan was that candidate. There was no doubt he connected with people in a way that establishment GOPers—guys like Ford, George Bush, and Nelson Rockefeller—just couldn’t.

Early in 1980, Sears and Black were ousted from Reagan’s campaign and Bill Casey took over. We felt we could win, as the field had been reduced to Reagan, Bush, and John Anderson. Six days before the primary, we talked Bill Casey into including a Serb Hall stop.

Before they came, I told the people from Brookfield—a strongly conservative, upscale suburb—“don’t come in a suit.” We didn’t want to look like the John Anderson crowd that had met elsewhere on the south side the week before.

Describing the south siders who packed Serb Hall that night, Craig Shirley remarked that the Milwaukee telephone directory was “jammed with listings of people whose names looked as if they’d gone through a Mixmaster. The scions of the Republican Party didn’t want these people with funny last names traipsing around their country clubs. These people drank cheap beer and ate kielbasa! Slavs who could or should have been Republicans were not, largely because the snobby Republicans didn’t want them.”

Donald Pfarrer wrote in the Milwaukee Journal that “it wouldn’t be accurate to say that Reagan had tailored his speech to the Serb Hall crowd. He struck the same themes and adopted the same tone as on earlier campaign stops in Wausau, Waupaca and Neenah.”

But that didn’t matter. As Pfarrer wrote, “the place was as jammed as it had been that night in 1972 when the campaigns of Humphrey and George McGovern met there. If there was a so-called country club Republican among the 500 or 600 working people, he had left his Harris tweeds at home.”

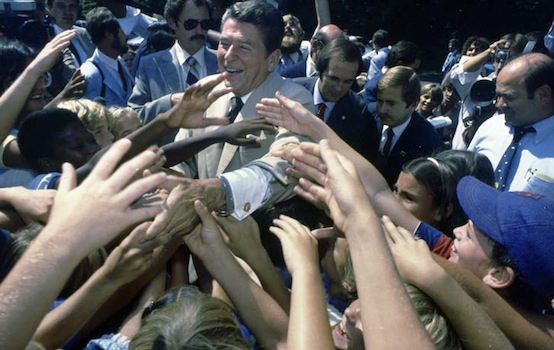

There was such a traffic jam outside, Ken Lamke of the Milwaukee Sentinel told me, we could have put 20,000 there. I remember that Reagan, as he always did, made it a point to stop in the kitchen on the way out and shake hands with everybody.

There was so much noise while he was speaking that I couldn’t answer questions from the national press covering his campaign. Reagan’s press guy told me to go in the kitchen and answer their questions. They wanted to know who these people were. Had we bussed them in from Brookfield?

I think that was the first time I used the term “Reagan Democrats.” We used to describe them as “Charlie Sixpack” or “Factory Freddies.”

Some perceptive national media saw the rising tide. Lynn Sherr of ABC reported that “judging from the way they showed up at a longtime Democratic meeting hall…a large number of blue-collar voters could go for Reagan.”

David Axelrod, the future mastermind of Barack Obama’s successful campaigns and then a Chicago Tribune political writer, wrote that “Reagan has been building, campaigning in blue-collar Democratic strongholds in search of conservative crossover votes. He astonished local political observers with a visit to Serb Hall, the mecca of ethnic Democratic politics.”

Tony Fuller of Newsweek remarked that with the Serb Hall speech, “Reagan didn’t merely break tradition, he shattered it—drawing an enthusiastic, overflow crowd of more than 1,000. One of the most significant political phenomena of 1980 has been Reagan’s ability to draw traditionally Democratic blue-collar support.”

George Bush had a $600,000 budget for Wisconsin and we had $125,000, but Reagan carried Wisconsin and the 4th District in the April 1 primary, getting 40 percent of the vote, compared to 31 percent for Bush and 28 percent for Anderson, a moderate Illinois congressman who wound up mounting a third-party campaign.

Perhaps more significantly, the Republican race drew about 60 percent of those who voted, compared to 40 percent in the Democrats’ three-way contest among Carter, the late Ted Kennedy, and Jerry Brown.

Shortly after the Wisconsin primary, Reagan declared in a speech that “on the farm, in labor unions, on the street corners of the cities, and in white-collar offices, there is a new coalition and I believe it is coming our way. The crossover voting of increasing numbers of blue-collar workers, ethnics, registered Democrats and independents with conservative values is beginning to take place.”

Gary Goyke, a veteran Wisconsin lobbyist who was then a Democratic state senator, stayed neutral in their primary contest, but recalled that “healing did not take place.”

Goyke said Reagan “put some sunshine into his side. His style was friendly, and the fact he’d been a Democrat at one time didn’t hurt him.”

The fall campaign built on the foundation we had built in Wisconsin, inviting Democrats fed up with Carter and their party’s leftward drift to join us, and presenting Reagan as the true heir to Franklin D. Roosevelt, the great communicator of his earlier era.

As Reagan told audiences regarding the shaky economy, “a recession is when your neighbor loses his job. A depression is when you lose yours. And recovery is when Jimmy Carter loses his.”

Reagan carried 44 states in an election considered too close to call by pollsters. Union members, ethnic whites, and big-city residents all gave Reagan far more votes than they traditionally had for Republicans.

“Before long, political experts spoke of a distinctive phenomenon, Reagan Democrats,” Samuel Freedman wrote in The Inheritance. They “located their epicenter in Macomb County, Michigan, an area of suburban Detroit thick with white ethnic, unionized factory workers.”

Some of us, though, knew months earlier that the Reagan Democrats were out there, and we didn’t have to cross Lake Michigan to find them. Over the next few decades, those Reagan Democrats would become comfortable in their new political home, although Bill Clinton was able to speak to and relate to some of them.

Before 1980, almost all of southern Milwaukee County was solidly Democrat. But by the turn of the century, several of the south suburbs were solidly Republican, while others, like West Allis, were closely divided. These areas responded to future Republican governors Tommy Thompson and Scott Walker, and eventually Donald Trump. But it was that night at Serb Hall that the spark was lit for the first time.

Bill Kurtz contributed to this article.

Bob Dohnal is a longtime conservative activist in Wisconsin. Bill Kurtz is a former Milwaukee Journal reporter whose work has been published in the New York Daily News and Our Sunday Visitor, a national Catholic weekly.

Comments