The Most Traditionalist Pub in New York

The second time I went to McSorley’s Old Ale House was with my fiancée and her maid of honor. I held the door for them like a good gentleman and then hung back to check my phone like a good Millennial. They made it about three steps into the dense press of bodies before one of the waiters accosted them: “Yuh here to drink, or yuh here to chat?”

It was only when I showed up that he started taking us seriously. The girls didn’t mind. The hostility only added to the charm.

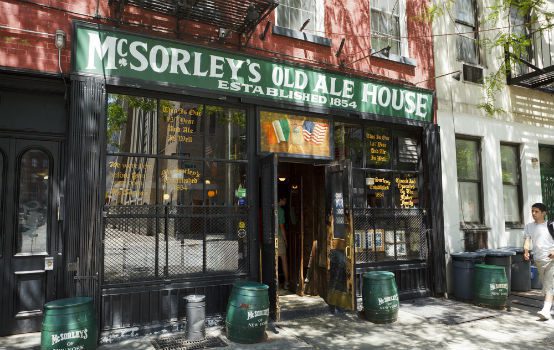

A bit of historical background will be helpful. McSorley’s is an Irish alehouse in lower Manhattan that was founded by Irish immigrant John McSorley in either 1854 or 1861. Over the years, its visitors have included Abraham Lincoln, Babe Ruth, Hunter S. Thompson, Harry Houdini, Boss Tweed, and Woody Guthrie. I say “either” in regards to the year of its founding because there is considerable disagreement on this issue and on a number of other points. So much of the alehouse’s history is oral or apocryphal, and its traditionalist bent has often placed it in conflict with New York City’s progressive and overbearing regulatory policies.

Here’s one example. In McSorley’s, one would be hard pressed to find a patch of bare wall. Nothing has been removed from the walls since 1910, and the decorations range from tasteful nude paintings to group photographs of mustached men from the 1890s to a wanted poster for John Wilkes Booth. The chandelier above the bar is festooned with wishbones. The story goes that soldiers about to depart for World War I (and possibly some who left for the Civil War; again, this is a purely oral tradition) left them there to retrieve when they made it home. The wishbones still hanging represent the boys who didn’t return.

Whether the story is true or not, soldiers in our interminable modern wars have taken up the tradition, and the old wishbones are treated like relics. The health department had to twist the owner’s arm to get him to dust them in 2011 (thankfully they’re once again fairly dusty), and one New York Times story describes a physical altercation breaking out when a health inspector tried to take one of them.

Much more famous is McSorley’s refusal to admit women until 1970, when a court ruling compelled equal access. In the 19th century, of course, it was expected that no honest woman had any business in a place like that, full of drunk, lascivious men whose breath stank of ale and raw onions. Even Dorothy Kirwan, who owned the place from 1939 until her death in 1974, wasn’t allowed in. Even after the ruling, she refused to be the first woman served, citing a promise she’d made to her father.

The first woman served was Barbara Shaum, who owned a nearby leather goods shop and often went over to McSorley’s after closing time to listen to one of the employees play the fiddle. Instead of focusing on Shaum, though, I’d like to contribute a new bit of oral history. Keep in mind, this story comes to you several degrees removed. Apparently, my fiancée’s father had a friend who was at McSorley’s the day they began admitting women. This friend saw a female television reporter come in and smugly record a segment about that latest triumph for the women’s rights movement. The camera stopped rolling, and she sidled up to the bar and ordered a glass of red wine.

The bartender grunted in response, “Ale.” McSorley’s serves nothing but its own specially brewed light and dark ale (often paired with cheese, crackers, raw onions, and hot mustard) in heavy glass mugs. I’m not sure what would happen if you asked for a glass of water.

The reporter tried again, “How about a gin and tonic?”

Another grunt. “Ale.”

Exasperated, she ordered an ale and drank it. A few minutes later, she asked where the ladies’ room was. The bartender pointed to the sole bathroom in the back of the bar. The reporter’s gaze followed his finger and then turned back to him, horrified.

“Heh,” he said. “If ye can drink wid us, ye can piss wid us.”

The single bathroom, as can be imagined, led to an oft-repeated scenario. A woman, uncomfortable of being in a bathroom with men, would ask her boyfriend to watch the door for her while she went. A drunk would stumble up to the door and demand to be let in. Fisticuffs would ensue. Finally, in 1986, McSorley’s was forced to install a women’s restroom.

The light misogyny my fiancée and her friend experienced on the way in still lingers, but everyone is fair game for the staff’s aggressive ribbing. Last time I went, the waiter asked me how long I’d been engaged, poked fun at me for moving too slowly, and then, as I got up to leave, whispered in my ear, “Keep her yer fiancée as long as ye feckin’ can.”

At a time when the Boy Scouts of America have been feminized to death, McSorley’s stands as a reminder of the bracing effect old fashioned 19th-century masculine energy can have. Some women enjoy that energy and some men don’t, but despite the admission of women, it endures.

McSorley’s is one of the few places I’ve visited that retains a sense of history, of tradition and continuity, of myth and orality. It’s a place where you can be seated next to a complete stranger at a communal table and listen to him tell you all about the mysterious man who, for the last 20 years, has called McSorley’s every Sunday at noon to ask, “Are you ready for your enema?”

It’s a place where culture grows organically in defiance of the leveling, micromanaging impulses of the state. It’s a place, as E.E. Cummings wrote in his poem “i was sitting in mcsorley’s,” where all is “sung and evil,” where the ale “never lets you grow old,” and where you are free to turn to the “shadow” seated next to you and ask “the eternal perpetual question”: “won’t you have a drink?”

Grayson Quay is a freelance writer and M.A. student at Georgetown University.

Comments