The Burkean Case Against Impeaching Donald Trump

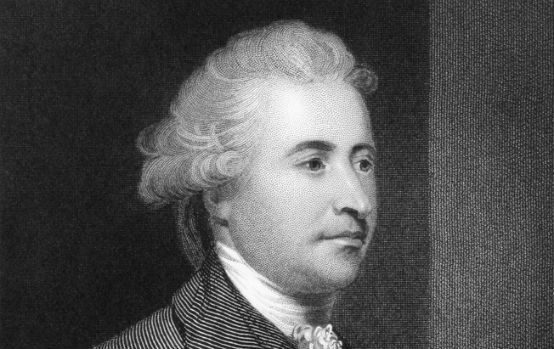

Published in 1790, Reflections on the Revolution in France is a scathing indictment of the French Revolution as well as the parties in England that supported it. Edmund Burke, the author, wrote of his ideological opponents, the revolutionary-minded leftists in the British Parliament:

Under the pretext of zeal towards the Revolution and Constitution, [they] too frequently wander from their true principles; and are ready on every occasion to depart from the firm but cautious and deliberate spirit which produced the one, and which presides in the other.

Burke’s rhetoric here is apt. He prefaces “zeal” with “pretext of” to make clear that this radical “wander[ing]” is a deliberate act of these British revolutionaries rather than some accidental overreach made in the throes of political zealousness.

Such sinister behavior, masquerading as patriotism, has unfortunately not been relegated to the history books.

Congressman Adam Schiff, ideologue-in-chief of the Democrats’ impeachment coalition, opened his public inquiry with the following:

If the president can simply refuse all oversight, particularly in the context of an impeachment proceeding, the balance of power between our two branches of government will be irrevocably altered. That is not what the Founders intended, and the prospects for further corruption and abuse of power, in this administration or another, will be exponentially increased.

These words, profound and bold, are comically inappropriate for the situation at hand. Much like former special counsel Robert Mueller’s infamous Russia probe, the more we find out about President Trump’s relationship with Ukraine, the less we see reason to care.

The Democrats are active proponents of “ready-fire-aim” accusations and strategies. It would seem that Donald Trump committed an impeachable offense the day he took office, and the last three years have been spent looking for the “high crimes and misdemeanors” to substantiate his removal.

While some might fairly argue that President Trump’s questionable rhetoric and off-the-cuff decisions haven’t exactly made strong arguments in favor of what his diehard supporters behave like is moral infallibility, poor word choices and coarse mannerisms are hardly tantamount to the precedent for impeachment set not only by the U.S. Constitution but by the impeachments of America past.

What Schiff has done is to distill the rights endowed to the people by the Constitution into three radical tenets, as described by Burke:

- To choose our own governors.

- To cashier them for misconduct.

- To frame a government for ourselves.

Burke points out the dangers of euphemizing what are truly revolutionary actions into righteous-sounding virtues. “Misconduct” being an irresponsibly flippant requisite to dethrone a king, Burke does not emphasize in any implicit way the significance of how cautious, reserved, and thoughtful a proper reorganization of government must be.

This spirit of conservative caution was in fact practiced by the very Founders Schiff invokes. The careless idea of “misconduct” was almost included in our Constitution, in the articles outlining how a president may be impeached. Yet James Madison took great issue with the criteria of “maladministration” that was to be added to “treason and bribery.” As Madison wisely noted: “So vague a term will be equivalent to a tenure during pleasure of the Senate.”

Madison then set a much higher precedent for impeachment by adding the words “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Much like Burke, he understood the danger in enabling a people to depose their duly elected president with subjective opinions of underperformance.

Perhaps Schiff does not clearly understand what it is that the Founders intended. For neither their Constitution nor the constitutions that influenced it intended our executive to serve at the pleasure of the House or Senate.

Quite the opposite, in fact. Madison saw a convenient impeachment process as undermining executive power. Although he still understood it as “indespensible” for protecting the polis, he recognized (in Federalist 65) how the personal and confrontational nature of an impeachment would likely lead to unjust rulings:

In such cases [of political polarization and animosity] there will always be the greatest danger that the decision will be regulated more by the comparative strength of parties, than by the real demonstrations of innocence or guilt.

The recurring theme from the Father of the Constitution, as well from Edmund Burke, is that of sagaciousness. Keeping that in mind, let us have authentic zeal for the principles of our American Revolution and Constitution, and reject the distortion of our traditions and history that would do away with political prudence in favor of ideological dogma.

John Welnick is an Army vet, born and raised in San Diego. He works in conservative talk radio for Salem Media Group.

Comments