The Best Tweeter in History Died Decades Ago

The best advice for Twitter users was written back in the 20th century: “The writer who has not tortured his sentences tortures his reader.” The author of that maxim was Nicolás Gómez Dávila. He was a Colombian intellectual whose best thinking came over hundreds of aphorisms of little more than 140 characters. He called them Scholia. They were brilliant, synthetic, ironic. And many of them are coming true, starting with: “The modern world seems invincible. Like the extinct dinosaurs.”

In the age of fragmented Twitter thinking, Gómez Dávila emerges as more relevant than ever, 107 years after his birth. Why is the world is baffled by this health crisis? Gómez Dávila explains it to us: “To be modern is to view another’s death without emotion and never to think of one’s own.” That’s right! We were convinced something like this could never happen to us and we were wrong.

Reactionary but above all visionary, Gómez Dávila detested the idea of progress, gregarious thinking, and everything that came out of May 1968. His love of the modern world was very limited: “Each day it becomes easier to know what we ought to despise: what modern man admires and journalism praises.” I suppose that includes high-waisted pants for men, over-intelligent appliances, and gender language. Gómez Dávila also saw the arrival of a chameleonic left wing: “Imbecility changes the subject in each age so that it is not recognized.” Perhaps that is why those nostalgic for the summer of love have now become apostles of climate change. In their defense, I must admit that what concerns them in both cases is the issue of warming.

Gómez Dávila’s universe is pessimistic and ironic, but supported by faith. He respected Nietzsche, but he dismissed the nihilists and atheists by downplaying their messianic drama: “What is important is not that man believe in the existence of God; what is important is that God exists.” In the end, the essential thing was not man, but God: “Man is important only if it is true that a God has died for him.” Thus the German philosopher who decreed with great pomp the death of God was affectionately mocked: “The death of God is an interesting opinion, but one which does not affect God.”

Gómez Dávila anticipated the moral suicide of postmodern societies and signaled the fool with surgical precision: “When today we hear someone exclaim: ‘very civilized!’ ‘very humane!,’ there can be no doubt: we are dealing with abject stupidity.” Gómez Dávila was, above all, an unparalleled imbecile detector. That’s why, in the middle of the 20th century, he anticipated that they would try to impose on us “universal” values that are no more than particular extravagances: “The fool does not content himself with violating an ethical rule: he claims that his transgression becomes a new rule.”

Back to the pandemic. Some are trying to convince us that the Chinese model is the solution to the coronavirus crisis. They forget one thing: the blame for the pandemic lies with China, which denied its existence and gagged those who warned of the risk. “The fools are indignant only against the consequences,” wrote Dávila.

Dávila was not a name caller but an intellectual. He knew how to put his finger on the sore spot: “The tragedy of the left? To diagnose the disease correctly, but to aggravate it with its therapy.” He explained it even better when he spoke of revolutions as historical cons: “The authentic revolutionary rebels in order to abolish the society he hates; today’s revolutionary revolts in order to inherit one he covets.” In the end, “Every revolution exacerbates the evils against which it breaks out.” Just ask the Venezuelans.

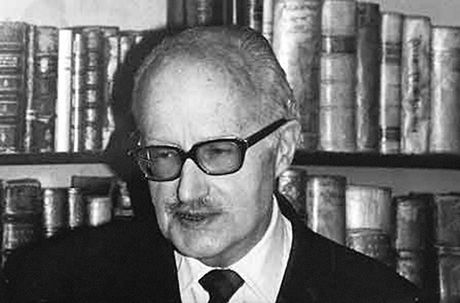

An aristocrat, his needs covered by inheritance, Dávila lived holed up in his library of more than 30,000 works for most of his life, dedicating himself to family, to simple intellectual life, and to the friends who frequented his famous gatherings. His world vision abhorred all collectivist enthusiasm, perhaps because it emanated from his faith in God. He knew that salvation was individual: “A decent man is one who makes demands upon himself that the circumstances do not make upon him.“

As a traditionalist Catholic, he was not complacent about the faithful of his time. I suspect that if he ever came close to losing his faith, it was when the church eschewed the Latin mass. Dávila confronted Christianity with a futuristic scholium that today seems to strike at our conscience: “Religion did not arise out of the need to assure social solidarity, nor were cathedrals built to encourage tourism.” By the way: what is left now that all the churches are closed because of the pandemic? God. The only thing that is really irreplaceable.

During his 80 years of life, Dávila delivered blows on all sides. He addressed hysterical sexual liberation with words that, in the midst of the pandemic crisis, no one can doubt: “Despite what is taught today, easy sex does not solve every problem.” To contemporary artists and architects, he stated: “The relativity of taste is an excuse adopted by ages that have bad taste.” To the intolerant, he counseled: “Let us learn to accompany those we love in their mistakes, without becoming their accomplices.” To the new puritans of the post-modern left, he warned: “Dying societies accumulate laws like dying men accumulate remedies.”

Also noteworthy was his skeptical analysis of the role of the media. On one hand, he downplayed the importance they gave themselves. On the other hand, he predicted exactly what we are experiencing today, when information and manipulation spill out of control and over the networks: “The media today allow the modern citizen to find out about everything without understanding anything.” Was he talking about Twitter?

Dávila despised rationalists, stripped progress bare, ridiculed democracy, and blasted the new secular religion imposed by an omnipresent state. But he was not just a stick of dynamite caught alight. He also found kindness, peace, and humor. He loved literature and language. He loved God. All his work seemed to be a melancholy homage to the vanished world of his childhood, an ode to tradition. Everything that represented his life and work can be summed up in one of his most beautiful Scholia: “Happiness is a moment of silence between two of life’s noises.” Although, perhaps because I’m a journalist, or because I have a huge poster of John Wayne presiding over my office, or because I’m a Christian, or because I’m European, or perhaps for all of the above, my favorite Dávila scholium is “Every man lives his life like a pent-up animal.”

Itxu Díaz is a Spanish journalist, political satirist, and author. He has written nine books on topics as diverse as politics, music, and smart appliances. He is a contributor to The Daily Beast, The Daily Caller, National Review, The American Conservative, The American Spectator, and Diario Las Américas in the United States, and columnist at several Spanish magazines and newspapers. He was also an advisor to the Ministry for Education, Culture and Sports in Spain. Follow him on Twitter @itxudiaz or visit his website www.itxudiaz.com. This piece was translated by Joel Dalmau.

Comments