The American Mind: Closed After All These Years

The Closing of the American Mind turned 30 this year. The fact that every five years now there is a retrospective is a testimony to its staying power, though it may also say something about the number of middle-aged writers on the right who cut their teeth on the book in their salad days. I count myself a member of that motley crew, having read and superficially understood it as a college junior and then periodically gone back to it many times over the years with gradually increasing background knowledge.

Some elements of Allan Bloom’s analytical framework are frankly inadequate. He is too perfunctory in dismissing the contribution made to knowledge about human nature by the sciences, and his Great Books/Thinkers list is missing a figure the right makes a grave mistake in ignoring: Darwin. Rigorous evolutionary thinking connected to empirical research into the foundations of human behavior and social order offers some of the sturdiest support for conservative politics, and the right would do well to embrace these findings.

The book’s second section (“Nihilism, American Style”) lays out the complex intellectual history undergirding Bloom’s description of the state of the university, and its obscurity for readers not already thoroughly grounded in the ideas it presents is only its most obvious weakness. Too much is made to depend on the lasting importance of the insights of Locke and Rousseau on human nature, and too much in contemporary behavioral science shows that their systems will not bear that weight. Locke thought human beings were essentially unmarked at birth by our animal nature, and Rousseau believed it was only social institutions that make us selfish and competitive. The Darwinian evolutionary perspective tells us considerably more of lasting importance about what we are and what the social world likely can and cannot do to alter that.

Despite these blind spots, in all the most important ways the book has scarcely aged at all. The first (“Students”) and the final (“The University”) sections remain invaluable for an understanding of the predicament of higher education in America, and serious thinkers on right and left should reread them from time to time to remind themselves of what has gone wrong and how it happened.

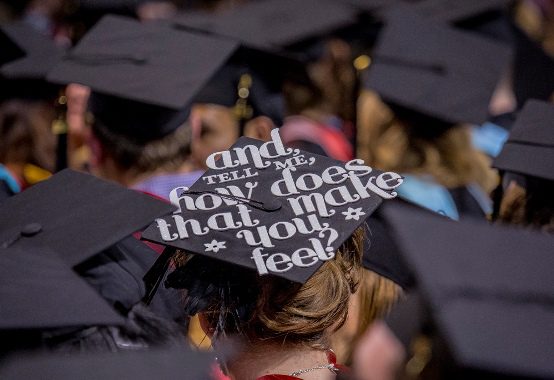

Bloom claims the culture of today’s college students is radically impoverished, and he provides examples from the favorite books they no longer have to the fatuous music they enjoy that have been doing the good work of infuriating cultural levelers now for three decades. But is he right? Almost certainly, and things are only getting worse. I have known innumerable students distributed more or less evenly across my nearly 20 years teaching in universities who perfectly fit Bloom’s description, but it is clear to me that something important has changed recently. These days, students are not simply ignorant of the sources of their culture. They no longer feel the responsibility to address this ignorance (which is in any event a more or less unavoidable consequence of youth), and they are quick to attack the things they do not understand for not fitting into their Twitterized cognitive frame for understanding all things. One depressing example will perhaps suffice. A student of my acquaintance at an elite liberal arts university, commenting on the Musée du Louvre after a first visit in which she found she was not intellectually prepared to have anything more than a bewildering experience, did not wonder what she might have missed in her youthful immaturity or how her expensive education had cheated her by not better preparing her for such encounters. Instead, she blithely dismissed one of the world’s great collections of art as “a museum of whatever.” Her scornful summary evaluation: “#overit.”

The final two chapters (“The Sixties” and “The Student and the University”) constitute the book’s core, and the brilliant light they give off has not faded with the years. Here, Bloom methodically exposes the 1960s counterculture’s caustic corrosion of American higher educational culture by focusing intently on the infamous 1969 armed campus takeover by black nationalist students desirous of the creation of an African Studies program at Cornell, where Bloom was employed at the time. This catastrophic failure of everything a university should be is the inevitable and indeed the intended result of the seemingly innocuous and democratic mantra of ‘inclusion’ and ‘openness’ at the curricular level. If bedrock educational values cannot be asserted and competing ideas cannot be comparatively evaluated by reference to an objective ruler for discerning the good from the bad, the inexorable result is a murky, relativist haze in which the only remaining mechanism for choosing is the volume, the emotion, and the physical force generated by the jostling competitors. In this context, students with rifles become interlocutors just as legitimate as any others, and we reap what we have sown in the fields of progressive political resentment. Rioting students and their irresponsible faculty advisers at Middlebury College and elsewhere, are you listening?

The response to the publication of the book in the scholarly world was predictably combative in an emotionally ideological manner, neatly summarized by Martha Nussbaum’s preposterously turgid read in the New York Review of Books. But the situation was different in the non-scholarly press, and the interpretive space between where we were in 1987 and where we are now is effectively gauged by looking there. Thirty years ago, the New York Times’ Christopher Lehmann-Haupt reviewed the book fairly, even favorably, and Robert Pattison at The Nation wrote at least one phrase sufficiently positive to merit its inclusion among the back cover blurbs. Try to imagine the book under the gentle ministrations of the bombastic writers at those two publications today, and try to imagine it not being denounced within a few phrases as Satanic or worse. Just try.

In the end, the value of Bloom’s case lies in his deep learning and intimate contact with the cultural values that created the Western universities. He fully recognized how insufficient it is to denounce the mess we have made of late, though that work of demolition is required. We must also know what we ought to be doing instead. What, he asked, are the questions to which competent universities should be attempting to speak, the questions by which properly-situated students should be motivated? His humble suggestions: “Is there a God? Is there freedom? Is there punishment for evil deeds? Is there certain knowledge? What is a good society?” His fear, which I share, was that we might be too far gone to even begin to fathom what we miss in evading or short-changing these questions.

We’re “#overit.”

Alexander Riley is the author of Angel Patriots: The Crash of United Flight 93 and the Myth of America.

Comments