The Ahmari-French Debate Was About Theology, Not Politics

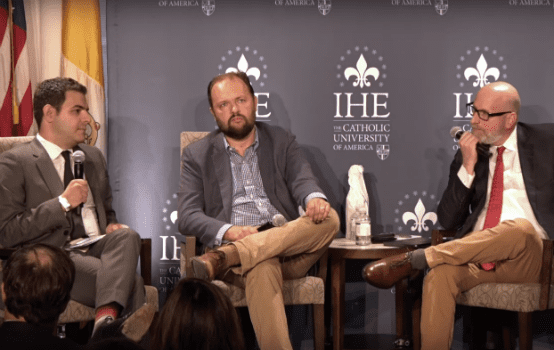

Last Thursday, at Washington D.C.’s Catholic University of America, two representatives from different sides of the conservative divide faced off. The New York Post’s Sohrab Ahmari and National Review’s David French sat in armchairs on a Heritage Hall platform, flanking moderator and New York Times commentator Ross Douthat.

Before the debate even began, there was a pseudo-hysteric energy permeating the room. Everyone’s brow seemed a little furrowed, perhaps because we’d all arrived expecting an ideological brawl. And boy did we get one. French had shown up in a mood of obvious indignation—and understandably so. It was out of nowhere that Ahmari had lambasted his moral and political courage in a May First Things piece. Throughout the evening, sincere anger over that attack peeked through French’s speech, and with each personal goad on the part of Ahmari, his face grew redder and redder. Indeed, when Ahmari cast suspicion on French’s bravery during his service in Iraq, Douthat, positioned between the two, appeared a little afraid for his physical welfare.

Yet in the end, it was all a circus, a pointless display. Because the two men ultimately weren’t arguing about politics, on which they might have found common ground. They were arguing about theology and faith.

Ahmari is fed up with the polite (or spineless) approach that conservatives such as French take when arguing with the Left. In his view, it’s genteel conversation that has pushed conservatism and the common good into retreat and allowed ardent leftists to claim victory in the culture war. Thinkers like French, who accept a pluralistic society and a need to give way to nicety as means of persuasion, are, he contends, the problem. They’re why conservatism is losing, as evidenced by the rates of abortion and the number of “Drag Queen Story Hour” advertisements that have popped up both in Ahmari’s Facebook feed and in cities across the nation.

He’s not the only one who thinks this. As leftism has become more militant and debauched, D.C. traditionalists and the Thomists of the Ivy Leagues have become ever more vocal in their plea for a better Christian game plan. Yet if we side with Ahmari, what we’re really saying is that an ordered society should very well look like a Catholic conception of it—perhaps even with the church playing some role in the American government, a so-called integralist state.

Of course, Ahmari was afraid to say that, because, even in the Bernie Sanders age, vocally advocating for state-imposed morality sounds far-fetched. It’s why, when French pressed him on the constitutional means to his preferred end, he stammered and proffered a Senate hearing. But that’s not what he wants, and he would have done well to just say so. After all, in his view, something must be done for the sake of our children and the welfare of the human soul. In the words of the Old Testament’s Joshua, we must “choose this day.”

He has a point. There’s cause for urgency, because everything we hold dear is at stake. The American Dream, long seen as a gift of opportunity and freedom, has become enmeshed with a rather bizarre religiosity to the idea that self-actualization comes through a form of celebrated selfishness. Yes, that’s a grossly reductionist view of the mainline liberal argument, but for those weary of a Randian culture that has produced little in terms of religious gains, it’s certainly what it feels like.

The problem is that, in dividing conservatives into teams, Ahmari has failed to account for differences in theology.

I’m from the Appalachian and exceedingly Protestant South. Most of the people who formed me fundamentally as a person would be hard-pressed to remember Pope Francis’s name, let alone be up to date on Catholic dogma. In fact, there’s a real reticence on the part of many Southern Protestants to even describe Catholics as Christians—Catholics, they say, pray to Mary and believe the pope is perfect. Catholics, they’ll often say too, don’t even believe in Scripture.

Of course, these beliefs are based in a reactionary religious isolationism that fears Catholicism lest it mess with the area’s deeply rooted Protestant culture. Still, there’s a basic idea embedded in there and it’s one that’s fundamental to the Protestant faith. We have an inherent distrust of man and his capability of being righteous—whether or not he calls himself Christian. It’s why we don’t have bishops, why we keep our churches relatively atomized, and why we don’t rely on the Church Fathers to interpret our Scripture for us.

We like the idea of the decentralized and the small. That can mean anything from a tiny steepled church on a country road to a Sunday morning worship service held in a one-bedroom flat. It also usually means keeping the federal government small enough that it can’t encroach on our lives. Our faiths are colored by a ceaseless emphasis on a “personal relationship with Jesus Christ.” It might deceive you at Sabbath worship, but our faith practice isn’t very corporate, and there’s a reason that’s the case. Sure, there are the appalling monstrosities called megachurches, where the staff is grotesquely large and politics stretch far and wide. But that’s still somewhat of a phenomenon, and plenty of us fail to see the Saddleback Churches of our time to be anything good. Why? Because, again, we like our structures small.

That goes for our social order, too. And to keep that order contained and manageable, our ideas have to be dispersed. That means letting our ideological enemies advocate for their ideas without fear of federal retribution for so doing.

Scripture, the only religious book to which we’ll pledge our allegiance, certainly doesn’t tell us to conquer our enemies. As French himself kept insisting last night, we’re called by Christ to show them. We’re to turn the other cheek, to advocate with love our morality and faith in a transcendent power. There isn’t supposed to be a holy war, even if a government allows for too much selfish individualism or too much debauchery on the streets of New York City.

In the Protestant’s eyes, there’s no real fix to be found in implementing a religious state, because that would give untrustworthy man far too much power. Whether it’s a pope, a bishop, or a certain New York Post editor with an ever-present look of scorn, all that power would do is corrupt them, because no man is truly incorruptible.

Yes, the culture war is utterly exhausting. The fact that children have been made to participate in drag queen readings is a tragedy so weighty that it should break our hearts in two. The number of human beings killed in the womb makes me mourn. Protestants are tired, too. It’s why a great number of us voted for Donald Trump. But we can’t see the Ahmari answer as a good one, even if it makes sense for a Catholic to buy into it.

When he was closing up the debate, Douthat asked French and Ahmari if they thought this disagreement was spurred by their theological differences. French hesitated, then resisted the idea. Ahmari, for his part, said yes, noting that Catholics are more contented in accepting societal infrastructure than Protestants. It was probably the first thing he said all evening that was totally correct. Even so, he’s undoubtedly going to continue with his tireless push for a Catholic state—as a means of kicking the elites from their spots at the top, returning a moral order to the common good, and helping the little guy find meaning once more. But it won’t work, because, for a writer so hung up on not losing sight of the little guys, he forgets that a great many of us are Protestants.

Emma Ayers is the managing editor at the D.C.-based media shop Young Voices.

Comments