Obama-Biden: Time for a Reunion Tour?

I remember a conversation in South Florida in January 2020 with Johnny Burtka, then the executive director of The American Conservative.

Before the pandemic transmogrified American life, the peculiarities of the coming presidential election seemed to loom larger than anything. Given this publication’s heterodox history, the continued rise of Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders was seen by us both, from a fiduciary perspective anyway, as complicated. Half our readers would probably dig him. At least at first. It would return—but whipsaw—the organization to its roots. TAC, of course, was founded to pelt a sitting Republican White House. And it was home to some of the great “ObamaCons.”

But I didn’t buy it. Personally, I made my bet on the establishment, a thing that has a pulse in the Democratic Party. The nominee, I held, would be Joe Biden, or the South Bend mayor Pete Buttigieg if needed, and if the powers-that-be could find an African American to vote for him. Sanders would be checked, I surmised, especially without the demonic presence of Hillary Clinton to exorcize in the Democratic primary. I filed a cover piece to that effect and called it a season, preparing for an election cycle where Biden challenged President Donald Trump as an unacceptable steward of a bull economy.

I got the first part right. But the terms of the later primary campaign and the contest against “Forty-five” shifted in a flash. First, Biden started out by performing abysmally. He came in fourth in the initial vote in Iowa. Then he placed fifth in New Hampshire, that land of comebacks. He followed that up with a comically distant second finish in Nevada, that land of fresh starts. That was after even some of Sanders’s union acolytes abandoned him (forget it, it’s Vegas).

I must have been his good luck charm, because it was only in South Carolina, the first (and last, it turned out) campaign state where I was on-hand, that Biden seemed to show up for work. It only took once. Biden, of course, romped to the nomination from then (late February) on and essentially secured a crowning in an unprecedented two-week blitzkrieg. He squeaked by just under the coronavirus buzzer. He accepted de facto control of the Democratic Party just as the nation embarked upon a previously unfathomable national lockdown.

In an anecdote recently exhumed by The Atlantic, the reality of the virus from Wuhan probably dawned on Biden earlier than most. The former vice president’s longtime collaborator, Larry Rasky, tweeted (presciently) on March 13: “COVID-19. You can’t bomb it. You can’t yell at it. You can’t ignore it. You can’t bully it. You can’t really blame anyone for it. The only thing you can do is solve the problem. That’s one card #DonaldTrump doesn’t have in his deck of magic cards.” On March 22, Rasky—described by The Atlantic as Biden’s press secretary from his first 1988 bid for the White House and someone “who never lost faith in him, even when others did”—was dead at 69, positive for COVID-19.

It matters not whether it was Biden’s personal proximity to tragedy or the coming extremism from his party on COVID-19 that inspired it. Biden’s hermetic strategy to reach the summit of global power was hatched in March. From that point, Biden borrowed from the “front porch campaign” of William McKinley, pitching himself as a steady, quiet hand opposed to a belligerent populist. The man who is to become “Forty-six” perfected his “basement campaign.”

The stratagem delivered a November victory, albeit amid shrieks and howls from Donald Trump and his entourage about voter fraud, this all amid an unexpectedly close result. 2020 was a farrago. With such a stealthy campaign, the question looms larger than normal with a new president: What’s Joe Biden going to do with all that power? Two new books try to get at this.

Biden’s prospective appointments so far sound like Barack Obama’s third term: Antony Blinken for secretary of state, Alejandro Mayorkas for homeland security chief, Tom Vilsack once again for agriculture secretary, Janet Yellen for treasury secretary, Jake Sullivan for national security advisor, John Kerry for special climate envoy, Jen Psaki for White House press secretary, and Ron Klain as chief of staff. All served the 44th president (Klain led the response to the Ebola crisis).

The former president himself, intentionally or not, cultivated such chatter by releasing his long-awaited memoir (or the first part of it), A Promised Land, soon after Election Day.

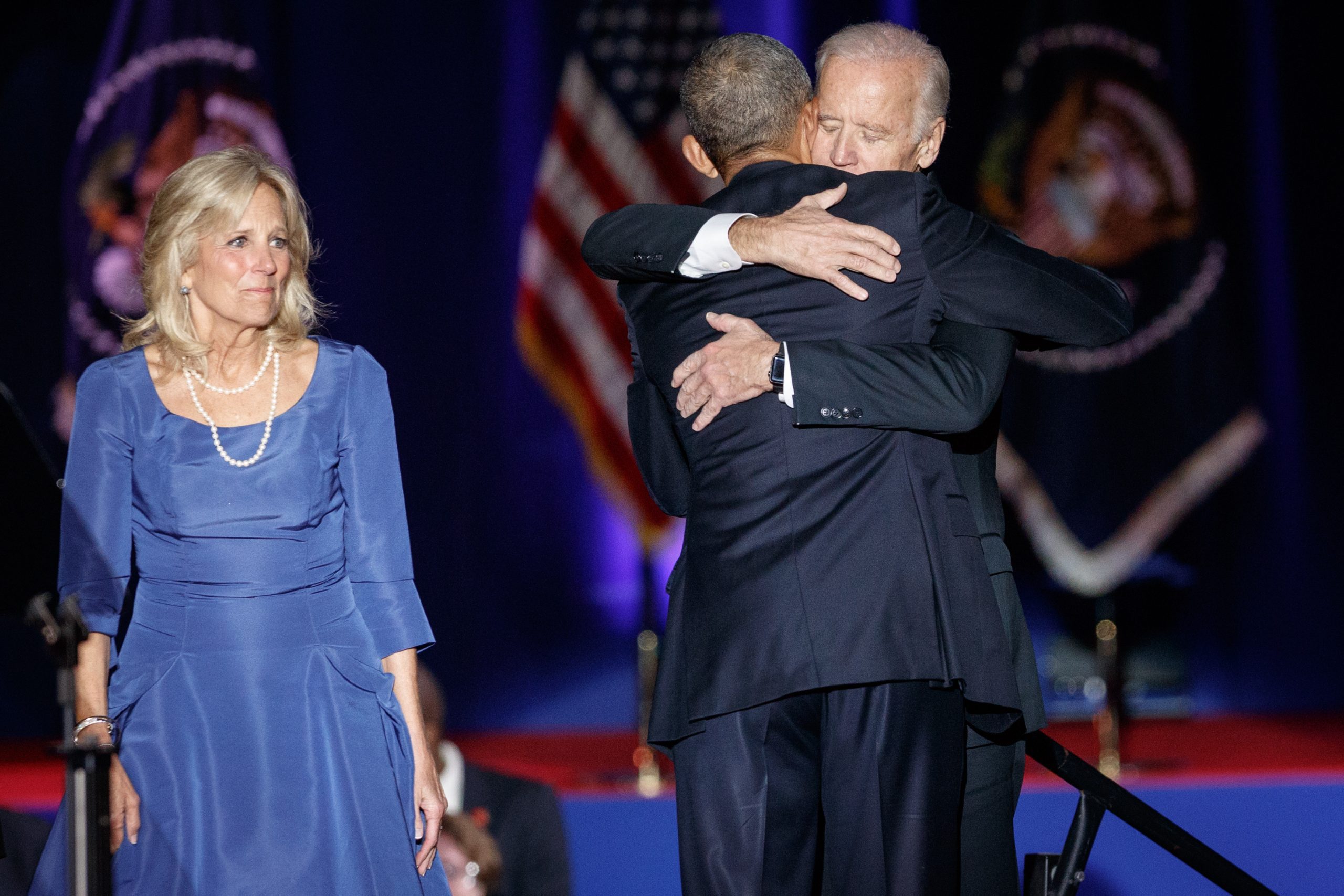

“If I was seen as temperamentally cool and collected, measured in how I used my words,” Obama writes, “Joe was all warmth, a man without inhibitions, happy to share whatever popped into his head.” Obama says it “was an endearing trait, for [Biden] genuinely enjoyed people”—implying, interestingly, that he did not. But “Joe’s enthusiasm had its downside,” Obama reminds. “In a town filled with people who liked to hear themselves talk, he had no peer.”

Mostly Obama speaks warmly of his former lieutenant throughout the book, emphasizing that he was “not disappointed” with his choice for running mate. But the subtly equivocal language that Obama frequently uses to discuss Biden is evidence of a rift between the two men that’s wider than generally understood.

It’s been reported since the 2012 election that Obama weighed dumping Biden from the ticket in his second bid for the White House, flirting with Hillary Clinton. That insult was merely a precursor. Obama and the Democratic establishment would essentially muscle Biden from the 2016 race. It’s true that Biden was grieving from the tragic loss of his son, Beau, the former Delaware attorney general and the second of his children that Biden has outlived. But aside from family, Biden, elected to the Senate at 29, knows little else besides politics. He tried in 2016.

“It’s been a little hard for me to play such a role in the Biden demise,” Klain wrote Hillary Clinton campaign chair John Podesta in autumn 2015. It’s memory-holed now, with the defeat of Clinton and the presidency of Donald Trump, and with Klain now set to serve as Biden’s chief of staff. But Biden was something close to forced out in 2015, with Obama the master hand in the behind-the-scenes parlor game—something he does not write about in his new memoir.

Biden’s public language at the time reflected this dictated reality. Speaking in the Rose Garden in October that year, Biden said: “As my family and I have worked through the grieving process, I’ve said all along what I’ve said time and again to others, that it may very well be that the process, by the time we get through it, closes the window. I’ve concluded it has closed.” Biden didn’t exactly deny his ambition, all things being equal. As Obama notes of Biden in his book: “His style was old-school, he liked the limelight, and he wasn’t always self-aware.”

In the days after Trump’s shock victory in 2016, Obama granted an interview to The New Yorker’s David Remnick. He did not mention Biden as his heir. Asked about the Democratic bench, Remnick writes, “He mentioned Kamala Harris, the new senator from California; Pete Buttigieg, a gay Rhodes Scholar and Navy veteran who has twice been elected mayor of South Bend, Indiana; Tim Kaine; and Senator Michael Bennet, of Colorado.” Obama does many things in A Promised Land, which runs 700-plus pages, but he does little second-guessing, especially of his own political instincts.

True to form, Obama discouraged Biden from entering the presidential race in which he would eventually triumph. “You don’t have to do this, Joe, you really don’t,” Obama was quoted by the New York Times as telling Biden in early 2019. Obama now has plenty of time to continue his memoir. Biden, far from the author’s first choice, must now write the next chapter of American history.

Bidenology is, of course, an emerging discipline with a surprising paucity of experts. One problem with having been in national politics for 50 years, and only reaching its apex while approaching 80, is that most of the people who have known you are dead. A young Biden is described in What It Takes by Richard Ben Cramer, the archetypical campaign book of New Journalism, but he’s only one character in a cast that includes George H.W. Bush, Al Gore, Gary Hart, Bob Dole, and other figures of the 1988 presidential campaign.

The Payoff: Why Wall Street Always Wins by disgruntled ex-Biden staffer Jeff Connaughton and The Unwinding by George Packer (where Connaughton is Packer’s source) grapple with the political figure who “disappoints everyone,” as longtime Biden consigliere Ted Kaufman is quoted as saying (Kaufman denies it). Biden has a biographer, the 93-year-old Jules Witcover, longtime collaborator of the late Jack Germand. He released Joe Biden: A Life of Trial and Redemption in 2019 before the pandemic and Biden’s late-life ascent.

Evan Osnos’s Joe Biden: The Biography appears to be the first real-deal attempt at the full treatment in what could properly be called the Biden years. Unfortunately, it’s not the full treatment.

Osnos has written compendiously about subjects as opaque as the Chinese government. Even for skilled journalists, America’s new president appears, in a way, even more enigmatic and unknown—odd for someone said to never shut up. Osnos had access to Biden during the pandemic and released his book in May. There are the interesting personal tidbits—“His hairline has been reforested, his forehead appeared becalmed,” Osnos notes—but much of the book tells the reader what he or she already knows: “The trials of 2020 dismantled some of the most basic stories we Americans tell ourselves.”

It’s just shy of 200 pages, and if that sounds light and rushed, perhaps it’s because it was, as only a year ago many were preparing to write Sanders treatises. Still, it’s probably as good a primer as we have—which, I guess, is worrying.

Biden told Osnos he wanted to govern as the most progressive president, as he sees it, since Franklin Delano Roosevelt. But Biden’s early personnel picks have revolted the progressive left. For instance, his choice for the Office of Management and Budget is Neera Tanden, the current president of the Center for American Progress. She has been a leading tormenter of Bernie Sanders supporters. Biden will send her before the Senate Budget Committee, where Sanders is ranking member. One needn’t be a member of the honored society to spot mafia tactics.

Biden told Osnos he wanted to govern as the most progressive president, as he sees it, since Franklin Delano Roosevelt. But Biden’s early personnel picks have revolted the progressive left. For instance, his choice for the Office of Management and Budget is Neera Tanden, the current president of the Center for American Progress. She has been a leading tormenter of Bernie Sanders supporters. Biden will send her before the Senate Budget Committee, where Sanders is ranking member. One needn’t be a member of the honored society to spot mafia tactics.

For all his rifts with the 44th president, perhaps by default, Biden is relying heavily on the Democratic establishment that once quietly tried to sidestep him. Even the choice of Osnos for an authorized biographer implies Biden is keeping it in the family—the Obama-Biden family—despite it all. Who was the publisher of Obama’s first memoir, Dreams from My Father, in 1995? Peter Osnos of Time Books, the father of The New Yorker’s Evan.

Maybe the key to understanding the future has less to do with Biden’s ideology than his temperament and style. “I sensed [Biden] could get prickly if he wasn’t given his due, a quality that might flare up when dealing with a much younger boss,” Obama writes in his new book. No such problem now.

Hillary Clinton was reported to have impressed Obama, previously her bitter rival, during his administration with her note-taking and preparation. Biden, in his youth a deeply indifferent student, took a more extemporaneous approach. What does America look like under Joe Biden? Maybe a country about to wing it.

Comments