Mr. Mehan’s Virtuous Little Animals

Mr. Mehan’s Mildly Amusing Mythical Mammals, by Matthew Mehan and illustrated by John Folley (TAN Books, 2018), 140 pages.

The Handsome Little Cygnet, by Matthew Mehan and illustrated by John Folley (TAN Books, 2021), 48 pages.

In recent years, the culture wars have spread to include even books aimed at children. This has largely been through a slew of books dedicated to “woke” politics, as progressive activists seek to catechize their children into their faith. These books—with such titles as The Antiracist Baby and A is for Activist—seek to capture children’s imaginations from an early age, and shape them into the kinds of citizens that progressives desire. And it’s not hard to see why. Since at least Plato, it has been recognized that education requires shaping the souls of children as early as possible, and forming what Edmund Burke called the “moral imagination”.

Political theorist Claes Ryn has written compellingly on the failure of conservatives to pay attention to culture and the attendant cultivation of citizens, noting that “many self-described American intellectual conservatives have a thinly veiled disdain for philosophy and the arts . . . The ruling assumption of the now dominant strains of intellectual conservatism seems to be that the crux of social well-being is politics: bad politicians ruin society; good politicians set it right.” As important as political engagement is, this singular focus on politics, he rightly notes, has led to disastrous consequences for cultural and political conservatives as progressives have gradually—but aggressively—assumed control of the cultural high ground, from the arts, to the academy, to literature, to pop-culture, to the media, so on.

If political losses have been presaged and reinforced through cultural capture, then clearly political action will not be enough to turn the tide. Conservatives will need to think seriously about—and relearn—how to once again shape the moral imagination of the younger generations. Thankfully, someone has already begun that work.

Matthew Mehan, director of academic programs and assistant professor of government at Hillsdale College’s Van Andel Graduate School of Government in Washington, D.C., has produced a pair of books, in conjunction with classically trained artist John Folley, aimed at the formation of moral imagination for children. Mehan—who holds a Ph.D. in literature from the University of Dallas and who spent 20 years teaching at the prestigious Catholic boys high school the Heights School—and Folley—who holds a B.A. from the University of Notre Dame in fine arts and philosophy and who studied with some of the great masters of the “Boston School” of painting—are well-equipped to do this work.

The first book, published in 2018 by TAN Books, is alliteratively titled Mr. Mehan’s Mildly Amusing Mythical Mammals. At first glance, the book appears to be a simple children’s book of poetry, like so many others available. But further investigation reveals it to be a deep work of moral poetry aimed at middle school children with the express purpose of honing their literary and moral imaginations.

The first indication that there is more than meets the eye (for those who are in the know what to look for, at least) is the image included on the dedication page, a design clearly intended to reference the printer’s mark of renowned Renaissance humanist publisher Johann Froben—whose publications included St. Thomas More’s Utopia and numerous works by Erasmus, among others—and which itself references Christ’s admonition to be “wise as serpents and innocent as doves”.

The book is structured as a traditional “alphabet” book, with a “mythical mammal” representing each letter, and a poem accompanying each. Two of the mammals—the Blug and the Dally—become the main characters, and the poems loosely chronicle their interactions with various other mammals, which represent various lessons in virtue and character-building. The poems are carefully constructed in various recognized forms—haiku, sonnet, and so forth—and contain numerous references to classical and Christian literature.

For example, E is for “Evol”, whose name evokes both the English “evil” and the Latin “evolare” which means “to fly up or out”. The Evol is said to be a cave dweller who has lost his eyes from lack of use, and whose words indicate a concomitant loss of ability to see the meaning in nature: through his “science most wise” he interprets nature—the rain, the trees, the stars—as mocking rational beings with a chant of “I LOVE NOT YOU”. This references both Plato’s allegory of the cave, in whose shadows humans are said to be unable to see what is real, and the devolutionary reductionism of scientism which blinds us to the moral meaning inherent in the universe, seeing instead only cruel indifference in nature which reduces humans to little more than speaking apes.

Or again, W is for the “Double Vólle” a creature with two heads: one that has wings and seeks to fly, another that clings to the ground biting at rocks. As the name indicates (from the Latin volo via the Italian volle) this mythical mammal represents the divided will (“double wills”) referenced most famously by St. Augustine in his Confessions but also suggested by St. Paul’s anguished cry in his epistle to the Romans: “For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do . . . O wretched man that I am! who shall deliver me from the body of this death?”

The book is completed by substantial appendices which include an extensive glossary as well as an explication of the alliterations implied in the illumined letter illustrations, and an “I-spy” game which encourages readers to find various items in the illustrations. All this adds up to a feast for young minds just beginning to explore the bonae litterae of Christian humanism.

But what of younger children who are not yet able to comprehend complex literary allusions or Latin references?

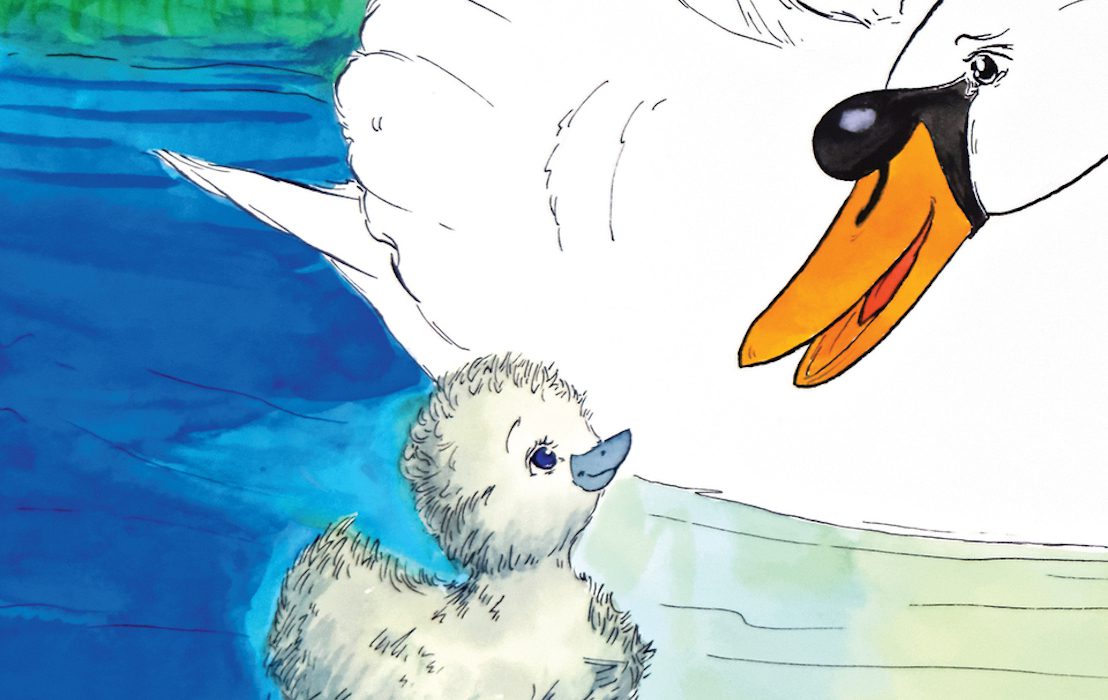

Mehan and Folley cover that territory in their latest book, released earlier this year, titled The Handsome Little Cygnet. On the surface, this beautiful book tells a simple and charming story about two swans raising their handsome little cygnet in the man-made lakes of Central Park in Manhattan. (I can attest from experience, it is one that toddlers will enjoy and ask to be read time and again.) But look a little deeper and one can see a deeply philosophical book, radically at odds with current trends in children’s literature and programming.

“Stay close to your mother and stay close to me” the father swan admonishes the cygnet. And the little cygnet responds: “I will, I will! I love you so. Why would I wander? Where would I go?” The father, knowing more of the world than the inexperienced cygnet, replies “But little cygnet, you must know, a swan’s heart can wander where a swan can never go.”

The cygnet sticks close to his parents for a time, until he becomes enraptured with wet graffiti paint that has been sprayed on a bridge and decides to roll in it to enhance his gray tone with colors. But rather than becoming colorful, he instead becomes sticky and dirty. After returning to his parents, he is instructed to ask the fish how to get clean, and, after being submerged, the fish clean him and return him to the surface restored.

Once the cygnet is restored to his former handsomeness, his father again admonishes him to stay close, to which the cygnet responds “I’ve no wish to wander when I finally must go.” The book ends with the father acknowledging that there comes a time when little cygnets must leave their parents, “Yet even then, we three swans will not be alone.” The final image depicts the swan family swimming into the sunset with a school of fish following in their wake, and an owl (a traditional symbol of wisdom) watching over them from his perch.

The book is an interesting reversal of Hans Christian Andersen’s “The Ugly Ducking” (here, the gray cygnet is “handsome” while his attempt to become more colorful ends up making him ugly), as well as a retelling of Christ’s parable of the prodigal son. It contains allusions to baptism (being submerged in water to wash away sins and be restored) and to the cleansing work of Christ as represented by the fish (ἸΧΘΥΣ, Greek for “fish”, symbolized “Jesus Christ, God, Son, Savior” to early Christians), as well as the aforementioned owl, symbolizing the role of wisdom.

Most contemporary children’s books and movies—rooted as they are in the spirit of modernity which is suspicious of all authority or tradition and deeply individualistic—reflexively encourage children to “follow your heart” or “be yourself,” long before they even have a developed sense of “self,” much less any moral center to guide them in their “being”. By contrast, The Handsome Little Cygnet shows what can happen when children are left to wander on their own, without the wise guidance of loving authorities or proper moral formation. We end up chasing things that seem attractive but are in fact ugly, creating messes that we cannot fix ourselves. Only through “staying close” to those who love us and will our good, the book suggests to us, can we hope to develop sufficient moral imagination and maturity to navigate the ugliness of a fallen world with integrity and prudence.

Taken together, these books provide a crucial start toward a regaining of a proper appreciation by orthodox Christians and cultural conservatives of the formative effects of cultural artifacts on the moral imagination of children. Arguments matter, to be sure, but the logical-rational part of the mind must be prepared and reinforced by the imaginative and the habitual if the arguments are to be received and, more importantly, applied. And, while the adage “politics is downstream of culture” has real limitations, it is certainly the case that those who wish to preserve Western culture and orthodox Christianity cannot afford to neglect the culture if they wish to succeed in their task.

Culture (from the Latin cultus, meaning “civilization, refinement, care, worship, training, education”, et al.) begins in the home, and with the very young. With these books, Mehan and Folley have given us, the parents of young children in need of cultivation in the great traditions of Christianity and the West, some useful—and beautiful—tools with which to do our work.

Comments