Kamala Harris Doesn’t Understand Her Own Political History

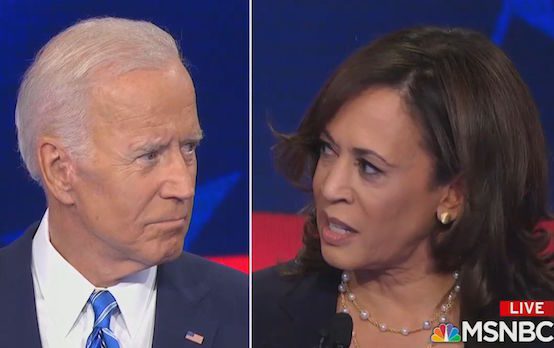

A Senate anecdote from the 1970s can shed light on the recent emotional exchange between California Senator Kamala Harris and former vice president Joe Biden at the recent Democratic presidential debate in Miami.

Harris excoriated Biden for earlier remarks in which he took a certain pride in his ability, early in his Senate career, to work with other senators whose political outlooks were antipodal to his own. He cited specifically Mississippi Senator James Eastland, a staunch segregationist, and with some apparent nostalgia talked about the “civility” of the Senate during those times.

In addressing Biden, Harris generously allowed, “I don’t believe you’re a racist.” But then she added, “I also believe—and it is personal—and it was actually very hurtful to hear you talk about the reputations of two United States senators who built their reputations and career on the segregation of race in this country.” She then excoriated Biden for his opposition to federally mandated busing to achieve school integration in the 1970s.

It wasn’t difficult to discern what Biden was trying to say when he invoked that earlier time: if today’s rancorous discourse and gridlock politics are a serious problem, as many Americans clearly believe, then he is a man who knows how to address that problem, in part because of his experiences from an era of greater comity.

It also wasn’t difficult to discern what Harris was trying to do in confronting Biden. She wanted to portray him as hopelessly out of date, too old and too much weighted down with the baggage of a long-gone era to lead in a more enlightened time. But it was less easy to understand what Harris was actually trying to say. What precisely was Biden’s transgression? Was it that he had worked with Eastland and other Southerners in that distant past? Or was it okay that he had done that but wrong that he should talk about it now? Would she respect him more if he had insulted his segregationist colleagues to their faces to demonstrate his political and moral purity? Or, having worked with them, should he insult their memory now to demonstrate, retroactively, his purity?

The anecdote that sheds light on this involves Minnesota Senator Walter Mondale, at the time one of the Senate’s most liberal members and a protege of the Senate’s leading progressive figure, Hubert Humphrey, for a quarter century. In early 1973, Mondale sought a coveted seat on the Finance Committee. But he feared that the Senate’s old bulls, including powerful Southern committee chairmen, would thwart his ambition because of his liberal views.

When he vented his frustration to J.S. Kimmitt, secretary to the Senate majority, Kimmitt posed a question: “Have you asked Jim for help?” He was referring to the same James Eastland invoked by Biden to the irritation of Kamala Harris. Eastland was a member of the Democratic Steering Committee, which doled out committee assignments to party members.

“Jim?” retorted Mondale incredulously. “That’s out of the question. We haven’t agreed on an issue since I got here.”

“Can’t hurt to ask,” said Kimmitt. “All he can do is say no. And he might surprise you.”

So a clearly nervous Mondale approached Eastland to seek his support. According to Finlay Lewis in his book Mondale: Portrait of an American Politician, Eastland looked on with a twinkle in his eye as Mondale sheepishly posed his request.

“Yup,” he said and moved on. Mondale got the assignment.

What to make of this story? Did Mondale sell out to the segregationists in his zeal for advancement? Hardly. Just two years later, he tied the Senate floor in knots in a valiant effort to blunt the impact of the Senate filibuster, for decades the leading weapon of Southern segregationists in their effort to kill civil rights legislation. The old bulls flew into a frenzy to thwart that effort, employing every parliamentary maneuver at their disposal, and nobody knew floor procedure like those wily old segregationists.

It was a spectacle that laid bare the raw emotions surrounding the underlying civil rights issue, with Mondale and the Southern oligarchs at each other’s throats—but civilly, of course. At one point, as Finlay Lewis relates, the Senate “became polarized over a murky motion to table a motion to reconsider a vote to table an appeal of a ruling that a point of order was not in order against a motion to table another point of order against a motion to bring to a vote a motion to call up a resolution that would change the rules.” He was only slightly exaggerating.

In the end, with parliamentary help from the Republican vice president, Nelson Rockefeller, Mondale managed to make it possible to kill a filibuster with a 60-vote floor count (the current procedure), rather than with the old two-thirds tally. It was a blow to the Southerners, including the same James Eastland who had helped Mondale acquire added stature in the councils of the Senate.

Why would Eastland do that, knowing that Mondale was an adversary? In part it could be attributed to Mondale’s habit of hanging out with his colleagues in Kimmitt’s office during slow afternoon sessions, drinking bourbon and trading stories and political intelligence. Eastland, a frequent habitué at those sessions, got to know Mondale and seemingly developed a liking for the engaging Northerner.

But more important was a widely shared feeling about what the Senate represented: all the political sentiments, hopes, fears, desires, angers, and animosities swirling through the polity at any given time—some of them hallowed, others unsavory or worse. But that was America. Eastland might have despised the impulses and aims and values of those Northerners who wanted to upend the culture and power arrangements of his state and region, but he knew he could never get rid of them. They emanated from areas of the country that had their own cultures and power arrangements and values, and that vital reality of American democracy had a certain sanctity.

Likewise with Mondale and his mentor Humphrey. They despised the Southern ethos, the racism and antidemocratic machinations to deny equal justice and political access to blacks across the region. They and many of their colleagues had committed themselves to doing all in their power to destroy the segregationist lock on the South. But those old bull committee chairmen didn’t just come out of nowhere; they shared a political milieu, however wayward in terms of the American creed and however much it needed reform. As Humphrey learned at the tutelage of Lyndon Johnson upon his Senate arrival in 1949, this had to be a long-term project, and in the meantime, it wouldn’t help the cause to declare those Southern pols to be evil or to look down upon them.

That was the comity that Biden sought to describe, with roots deep in the ethos and the political sensibilities of senators and their staffs. They could despise the Southern system while accepting those defending it and giving fealty to the democratic machinery that was the only legitimate means of upending it.

And upend it they did. Biden arrived in the Senate in 1973, nine years after the great 1964 Civil Rights Act and eight years after the even more consequential Voting Rights Act of 1965. That legislation marked a turning point for the segregationist South and the old bulls who represented it.

Kamala Harris’s attack on Biden indicates that she doesn’t understand any of this. Yes, there are dark elements to the American story, as there are dark elements to the story of every country, culture, and civilization in world history. But the triumph of liberalism over the segregationist South represents a chapter of light, to be appreciated by those who wish to be the leader of the nation. It is a story of American democracy that played out in part within a Senate that operated far more than today in a climate of civility, with a relative absence of knee-jerk recrimination and ill-disguised hostility even as huge and profound issues were being adjudicated.

By all accounts, Harris scored big with her Biden attack, and the commentators and mainstream media promptly hailed her as possibly the campaign’s most clever giant killer. That’s politics. But Biden’s invocation of the old days of Senate courtesy and efficiency doesn’t deserve to be dismissed with disdain.

Robert W. Merry, longtime Washington journalist and publishing executive, is the author most recently of President McKinley: Architect of the American Century.

Comments