In a Crisis, Humanism Trumps First Principles Every Time

Here in Old Town Alexandria, there is a white paper in every restaurant window. It announces that this establishment is closed, same as the one next door, and the next. Garlands of these sheets stretch down typically bustling blocks; peek past them into windows and you see ghostly dining areas with chairs atop tables. Virginia Governor Ralph Northam ordered the shuttering of all dine-in restaurants last week, and Old Town’s King Street, a major thoroughfare of lively boutiques and eateries housed in preserved 19th-century storefronts, has been rendered almost lifeless. The cigar smoke and gooey jazz notes from out one building, the crackling laughter from another, all gone. White papers—why do they feel more like death warrants?

The roads, meanwhile, are eerily still. Living in Old Town, one gripes about the local drivers same as anywhere else. Washington-area motorists? To appropriate the old Kennedy dictum, they have all the charm of Northern drivers and all the efficiency of Southern drivers. A Mercedes doing 40 in the passing lane with a middle finger out the window is emblematic. Yet robbed of those gliding taillights, that going of places and doing of things, you start to miss them. This is a city, after all, a “big rough turbine that is fueled by cigarette smoke and food and liquor,” as Graydon Carter once described New York. It’s supposed to be a little crammed, a little mad. Shut it all off like a switch and you forsake something fundamental. You remember what those abstract economic statistics are grasping at: motion.

The D.C. suburbs normally exist in a bubble, but these days they look a lot like the rest of the country. Neighborhoods everywhere are going dark, many of them less prepared for an economic freeze than is relatively well-off Old Town. New York City, the epicenter of the outbreak in the United States, has gone to sleep. Detroit, where the average life expectancy was already down to 62, is preparing to weather only its latest crisis in modern times. Donald Trump, once hopeful for an Eastertime economic tomb opening, has since warned that the pandemic could drag on through August. Dr. Anthony Fauci, the president’s medical adviser, is predicting that 200,000 could be killed, a third of the estimated death toll of the Civil War, our bloodiest conflict.

Yet amid the gloom, what’s most striking is just how characteristically everyone is behaving. Hollywood is full of protagonists who undergo drastic changes in times of strife—think of the hackneyed father who turns hardened killer after losing one of his children. Yet quarantined America has seen very little of that. Doctors rush through hospital corridors and save lives. Bureaucrats obstruct progress. The Chinese government lies and oppresses. The media bleeds the story for all it’s worth. Everyone behaves like he’s playing the role he was born to play, like it’s simply unfathomable that he should act any differently just because there’s a crisis.

Donald Trump, per usual, is sending more mixed signals than a malfunctioning lighthouse, questioning his own government’s line one day only to double down on it the next. His most fringe supporters, too, move according to type, musing over whether the coronavirus response is really a deep state conspiracy. The Tea Party briefly stalled the stimulus bill, as is their way, drawing the ire of most in Congress, as is their way. Nancy Pelosi also held up the package, in the name of (among other things) windmills.

Partisanship is just one of many old reliables weathering the pandemic. And not to be partisan myself, but all this anthropological consistency is vindicating the political right. Conservatism at its best is grounded in a realistic assessment of human nature—“the art of the possible,” as Bismarck described politics generally—in contrast to progressivism, which aspires to make man more than he can be. It’s the conservative who expects man to fall short, as we unquestionably have in recent days. Was any nationalist surprised when the authoritarian Chinese regime hid the extent of the virus and tried to blame it on America? Was any libertarian bowled over when Washington’s bureaucracy flubbed the response? Was any populist floored by the revelation that unscrupulous elites had dumped stock ahead of an impending recession? Each of these strains, whatever its faults, is built upon serious observations about human behavior, which the coronavirus has exposed for all to see.

Yet if the pandemic has acquitted some righties, it’s also brought fury down on others. Among them is Rusty Reno, the editor of First Things. Reno recently penned a pair of essays arguing that we should question the coronavirus response and keep churches open. “There are many things more important than physical survival,” he declared, “love, honor, beauty, and faith.” Elsewhere he tweeted, “We need to be careful about our first principles. There is a demonic side to a sentimentalism that insists we must save lives ‘at any cost.’”

Preventing priests and parishioners from dying en masse seems like a strange way of advancing the demonic. Still, I understand where Reno’s coming from. And he’s right that a singleminded focus on anything, however great the threat, can end up obscuring other values. How many of us would like to go back to the days after 9/11 and stop the AUMF, the Patriot Act, the harangues about how everything must change? Back then, we ran roughshod over limits and civil liberties in our rush to fight terrorism. We’ve paid for it dearly ever since.

But that’s still several degrees removed from saying we ought to risk lives by gathering in churches. Where I think Reno ultimately errs is that he’s focused to a fault on first principles, and unlike those other conservative philosophies, his principles have become disconnected from the reality on the ground. People are facing imminent danger, not hypothetical terrorism, and if forced to choose between that and their philosophies, they’ll save the lives every time. Our first principles always grow distant when death is a serious risk. They get replaced by, not sentimentalism, but a natural humanism that prizes protecting each other above all else. We don’t want dozens of congregants to fall ill, as happened after a Pentacostal service two weeks ago; we want the faithful alive so they can come back again and again. This isn’t secularism run amok; it’s what we’re wired to do.

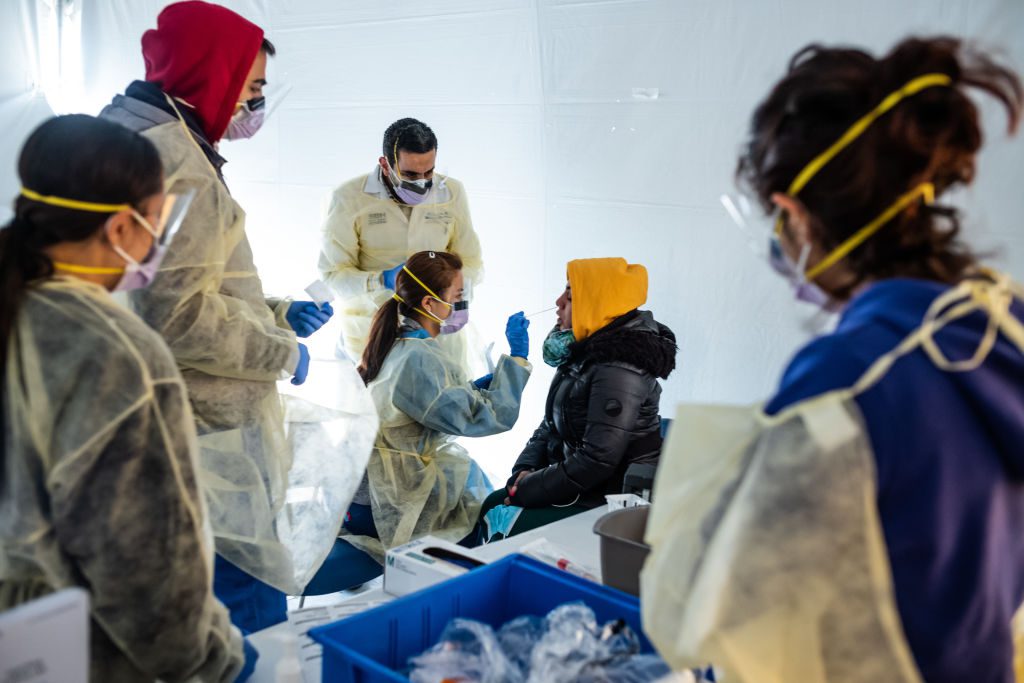

Edmund Burke said that in any prudential endeavor, “I shall always advise to call in the aid of the farmer and the physician rather than the professor of metaphysics.” To that end, over now to Craig Spencer, an emergency room doctor in New York. Last week, Dr. Spencer described on Twitter what it’s like to work at a hospital in the midst of the pandemic: patients short of breath, low oxygen, fevers, insufficient ventilators, infrastructure strained, lunches abbreviated, bleaching everything you own, social distancing from your own family, fear. Under the approach advocated by First Things—Reno 911, let’s call it—Dr. Spencer’s life would be made more difficult, maybe impossible. To forsake our responsibility to the vulnerable in this way would be unconscionable.

I’ve been on a Camus kick lately and I’m reminded now of his essay “Neither Victims Nor Executioners.” In it, he throws up his hands at decades of 20th-century ideological murder and declares that there’s only one utopia he any longer desires: that in which nobody is killed in the pursuit of a better world. Likewise should we now refrain from subordinating human lives to concepts and -isms. Remember, this isn’t permanent. The sooner we quarantine, the sooner the coronavirus will abate. The philosophical debates will resume; the sidelined values can be restored. And hopefully another anthropological constant will kick in: the need to celebrate after hard times are passed. What we’ll need is a jubilee, where those of us privileged to have jobs hit the roads and flood the restaurants and fill the pews. And why not? As all the failed social engineers of the ages will tell you, man is nothing if not stubbornly consistent.

Comments