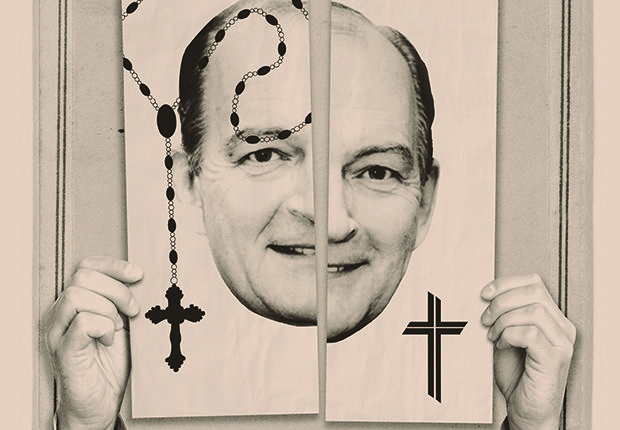

How Father Neuhaus Found GOP

High up on the domed ceiling of Vienna’s Karlskirche is an exuberant early 18th-century Baroque fresco called “Defeat of the Lutheran Heresy.” It depicts an annoyed Martin Luther, quill pen in hand, scowling as a po-faced Catholic angel puts his books to the torch while Luther’s co-author—Satan—recoils from the divine presence. The painting serves as a reminder that bitter antipathies between Protestants and Catholics continued after the European wars of religion ended. Protestants, for their part, long persisted in viewing the Catholic Church as the Whore of Babylon and the pope as Antichrist.

But the cleric, activist, and intellectual Richard John Neuhaus, according to Randy Boyagoda’s excellent new biography, saw the Catholic-Lutheran split as only a misunderstanding. Luther, in his view, was trying to reform the Catholic Church rather than break it apart. Neuhaus saw his own mission, as a Lutheran pastor for 30 years, as “the healing of the breach of the sixteenth century between Rome and the Reformation.” When he decided that reconciliation was impossible, he converted to Catholicism in 1990 and was ordained as a priest a year later; some called it the most prominent conversion since John Henry Newman’s.

While Neuhaus preached harmony and cooperation between Christian denominations, he became increasingly bellicose toward liberalism, modernism, and secularism. Though he had been a leftist in the ’60s, from the 1980s until his death in 2009 he emerged as a leader of the religiously oriented and mostly Catholic neoconservatives sometimes referred to as the “theocons.” Neuhaus was an important figure in Republican politics and the culture wars, infusing intellectual conservatism with distinctively Catholic elements and bringing not peace but a sword.

Most Americans, even most Catholics, have probably never heard of Neuhaus. He didn’t have the visibility of prelates like Cardinal John O’Connor and Archbishop Fulton J. Sheen, the fame of public intellectuals like William F. Buckley Jr. and Garry Wills, or the reputation of theologians like Reinhold Niebuhr and John Courtney Murray. Many of his three dozen books were too dense or prolix to command wide audiences, although his 1984 work The Naked Public Square received considerable attention and has continued to influence the debate over what role religion should play in American public life. He was a beguiling essayist, but most of his long, discursive, and bitingly amusing editorials appeared in First Things, the magazine he founded and edited, which continues to be an estimable publication but has never had a very large circulation. And his influence was mainly exercised behind the scenes and directed toward elites, particularly in the Vatican and the White House.

But Boyagoda persuasively argues that Neuhaus was a charismatic leader and original thinker whose contributions to American culture and politics make him someone worth knowing about. Neuhaus grew up in a small town in rural Canada, the sixth of eight children. He dropped out of his Nebraska high school and, after an interlude running a gas station in West Texas, graduated from seminary and followed in his father’s footsteps by becoming a Lutheran pastor, serving first in upstate New York and then in a poor and mostly minority parish in Brooklyn. Exposure to the hardships of urban life made him an early and energetic participant in the civil rights movement, which segued into antiwar activism. Neuhaus helped to found Clergy and Laymen Concerned About Vietnam (CALCAV) and for a while was a budding figure in the late ’60s political left, spouting glib pronouncements about the coming revolution. The Vietnamese people, he declared at the height of his radicalism, were “God’s instrument for bringing the American empire to its knees.”

By the early 1970s, however, a variety of factors conspired to distance Neuhaus from the left. One was his revulsion against the ecology movement’s push to save an allegedly overpopulated planet through sterilization and abortion. Neuhaus believed that population control was still colored by its origins in eugenics and scientific racism. He perceived that its targets were the weak and oppressed, both in the Third World and in his own Brooklyn congregation, as black and poor women accounted for a disproportionate share of abortions. Neuhaus’s view of abortion as a civil rights issue was an important continuity in his transition from left to right.

So too was his opposition to an overly rigid separation between church and state. A key Neuhaus dictum was that “politics is at the heart of culture” and “at the heart of culture is religion.” Therefore it was important that American politics, society, and culture should be open to religious perspectives and persons rather than devolving into militant secularism—what Neuhaus called “the naked public square.” Religion too should be public and patriotic; as he later put it, “God is not indifferent to the American experiment.” Even when Neuhaus presided over an antiwar church service at which resisters turned in their draft cards, he persuaded the assembled radicals to join him in a lusty rendition of “America the Beautiful.”

After the fall of Saigon, Neuhaus was distressed to find that few of his leftist allies were willing to condemn Vietnam’s Communist government for its human rights abuses; they had abandoned their ethical standards and aspirations, he charged, for the cause of personal liberation and the search for “the perfect orgasm.” He also felt that the mainline Protestant denominations had capitulated to a coarse and increasingly secularized culture.

Though Neuhaus had supported Jimmy Carter for president in 1976, he became an ardent Reaganite four years later. Soon he was making common cause with conservatives and neoconservatives on issues including anticommunism, military spending, abortion, defense of capitalism and traditional family structure, and opposition to the liberal pronouncements of the American Catholic bishops. One of his most significant initiatives came in 1994, when he teamed with former Watergate trickster Charles Colson to produce the Evangelicals and Catholics Together (ECT) declaration. ECT was an ecumenical attempt to find common ground between the two groups of religious conservatives, focusing on their shared opposition to abortion, euthanasia, eugenics, and population control as well as their advocacy of school choice, a market economy, religious freedom, and “a renewed appreciation of Western culture.”

Ralph Reed of the Christian Coalition pointed to Neuhaus’s work as one of the factors uniting Catholic swing voters with the Republican Party’s evangelical base in the critical 1994 elections. Indeed, the increasing political alignment of conservatives of all faiths is one of the major shifts in modern American politics. The tendency of evangelicals not only to vote like conservative Catholics but even to discuss social issues in a Catholic framework of natural law and moral reasoning would have seemed very odd not so long ago. Evangelicals had been slow to condemn abortion in the 1970s, for example, because they saw it as a Catholic issue, and reflexive opposition to Catholicism was a large part of how they defined themselves. Since many evangelicals in past decades would have denied that Mormons as well as Catholics are Christians, Mitt Romney could be considered a beneficiary of Neuhaus’s ecumenical efforts.

Neuhaus’s increasing prominence helped to make him a friend of Pope John Paul II, a collaborator with Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger (later Pope Benedict XVI), and an informal advisor to President George W. Bush, who looked to “Father Richard” for guidance on incorporating Catholic vocabulary and concepts into “compassionate conservatism.” Neuhaus and his colleagues at First Things in turn became largely uncritical champions of Bush, editorializing in favor of his domestic policies and characterizing his Iraq invasion as a “just war”—although Neuhaus did insist that torture, which the U.S. resorted to in its war on terror, was “never morally permissible.”

Unsurprisingly, Neuhaus in his last years became a target for those who saw him at the center of a theocon conspiracy to break down the separation of church and state and put an end to secular politics in America.

It was Neuhaus’s posthumous good fortune to have attracted Randy Boyagoda as his biographer. Boyagoda, a Sri Lankan-Canadian novelist and English professor, was an occasional contributor to First Things during Neuhaus’s editorship but met him only once. His account is sympathetic but objective, and he brings both scholarly acuity and a novelist’s gift for evocative scene-setting to every page. The book pivots adroitly from deep theological analysis to anecdotes about Neuhaus’s fondness for bourbon, cigars, dogs, Bach, and good talk. By the end, most readers are likely to share the author’s evident affection for his subject.

Boyagoda ably refutes charges that Neuhaus’s shift from left to right was motivated by opportunism or that he and his circle were extremists seeking to impose a quasi-medieval theocracy on America. Still, Neuhaus could be a more polarizing figure than he usually appears in this account. There isn’t much in the book about Neuhaus’s insistence that America is a Christian nation leading the forces of Christendom, his characterization of homosexuality as a pathology, his call for “intelligent design” to be taught in public schools, or his push to exclude Catholic Democrats from the sacrament of communion. Whatever the merits of these positions, they unquestionably were divisive and, as Neuhaus sometimes reminded himself, risked turning religion into partisan politics. “We can confuse our Christian hope with political success,” he warned the Christian Coalition, and “there is a danger that we confuse our political policy judgments with the judgments of God.”

Religious neoconservatism, tied as it was to Bush and Benedict, could not avoid being tarnished by Iraqi misadventures and Catholic sex-abuse scandals. By now, most social conservatives would concede that they have lost the public-opinion battle on same-sex marriage and perhaps assisted suicide as well, which has led many to question Neuhaus’s belief that liberal democracy and Catholicism are compatible. The result is that the Neuhaus/First Things position is losing ground both to liberalism and to the “radical Catholicism” that, as described by University of Notre Dame professor Patrick Deneen, “is deeply critical of contemporary arrangements of market capitalism, is deeply suspicious of America’s imperial ambitions, and wary of the basic premises of liberal government.” The value of this biography of Richard John Neuhaus, then, is not just as a work of history and remembrance but as a guide to coming conflict.

Geoffrey Kabaservice is the author, most recently, of Rule and Ruin: The Downfall of Moderation and the Destruction of the Republican Party, From Eisenhower to the Tea Party.

Comments