How a Moral Panic over ‘Stranger Danger’ Led to the Safety State

Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State, Paul M. Renfro, Oxford University Press, June 2020, 297 pages.

During the 1980s, large sections of the American public embraced the idea that a handful of horrific events were symptoms of a deep-seated national sickness. Intense focus by a rapidly expanding, multi-platform media transformed events that would have previously been local news items into durable national preoccupations. Moral panic ensued as millions of Americans learned of a national network of transgressors that had long been hiding in plain sight. Citizens displayed striking vigilance in rooting out this new disease, pushing successfully for public policies aimed at eradicating it. Immersed in the moment, few people gave much thought to the long-term consequences of these new policies. How little times have changed.

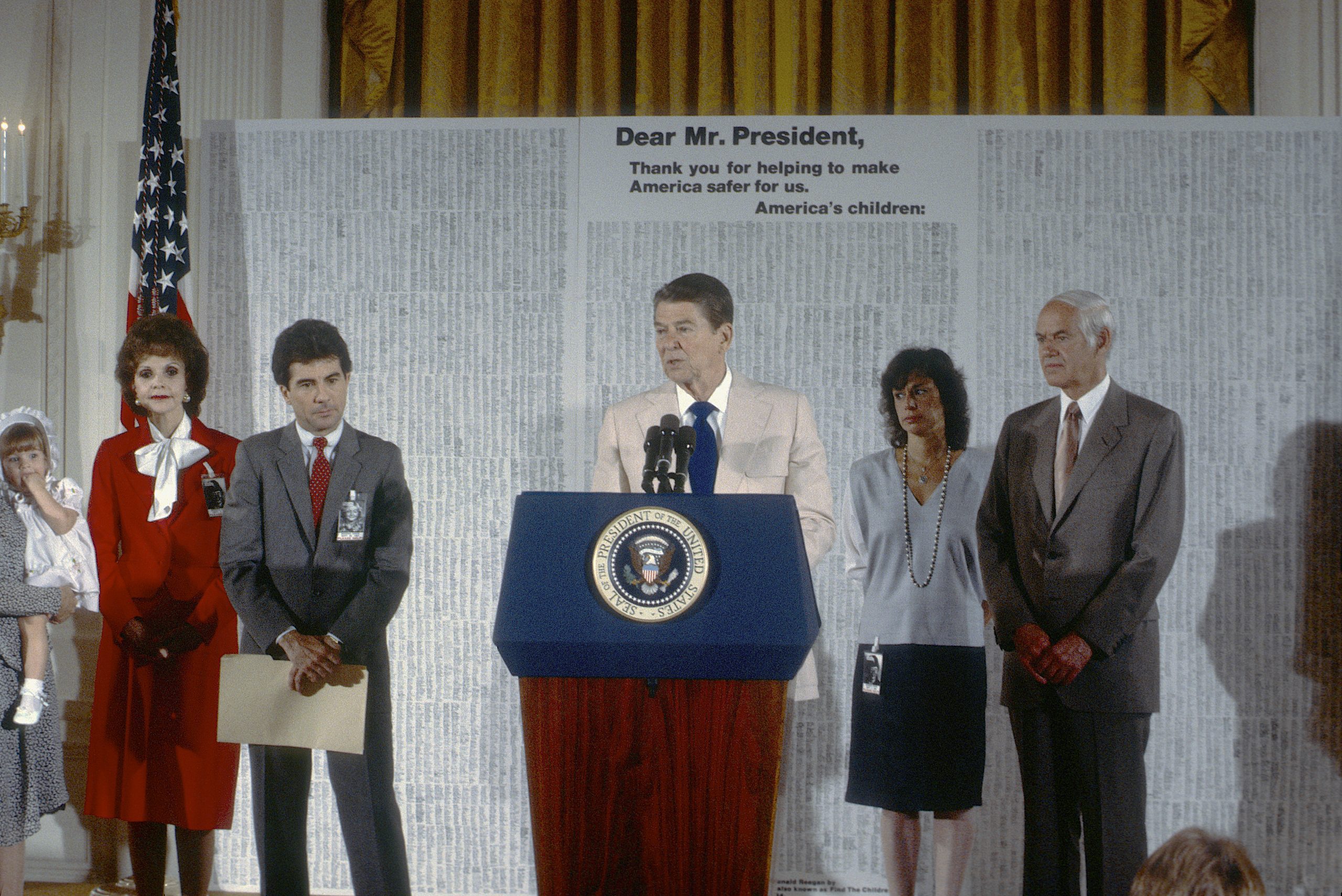

Paul M. Renfro’s excellent new book, Stranger Danger: Family Values, Childhood, and the American Carceral State is an engaging history of how a cluster of high-profile child abductions in the late 1970s and 1980s became catalysts for the expansion of state power, a corporatized national media culture that thrives on crisis, and a bipartisan political consensus built around the idea of security. Renfro revisits well-known kidnappings, including the cases of Johnny Gosch, Etan Patz, and Adam Walsh. Collectively, he presents them as the starting point for what he calls “the child safety regime.” Aspects of this regime include AMBER Alerts, sex offender registries, child fingerprinting, and state and federal legislation aimed at protecting children from potential predators. Backing all of these policies is a broad popular consensus deeply invested in the enforcement of the different elements of the regime.

The author demonstrates how a political and cultural climate emerged in the 1980s and 1990s in which the voices with the darkest visions of depravity received the most attention. In the Etan Patz and Johnny Gosch cases, sensationalized media coverage presented both abductions as the tip of the iceberg in large-scale and coordinated child abuse rings. A cottage industry of advocacy for “missing children”—a new and somewhat ambiguous term—emerged in response to the panic. John Walsh, the father of one of the best-known victims of stranger abduction, became one of America’s most recognizable public figures as a crime-fighting television host and victim’s rights activist.

Numerous other television saviors, including Nancy Grace and Chris Hansen, have followed in Walsh’s footsteps. Typically, these hosts are focused on rooting out the exploitation of children by strangers, a relatively rare phenomenon when compared to the much more numerous cases of abuse by family and close acquaintances. While some political leaders and institutions, most notably, the Department of Justice, were slow to grasp the symbolic power of the issue, the cause of protecting children from exploitation through powerful new legal tools became a ready-made crusade for legislators, bureaucrats, and broadcasters. Renfro is correct to emphasize the degree to which the child safety crusade played upon images of a white, suburban innocence threatened by the pathologies of the inner-city—namely people of color, gay men, and transients.

For the most part, Renfro writes clearly and concisely, though the book’s origin as a dissertation is sometimes apparent, as when, for example, Renfro pauses to recite the relevant scholarly catechism on urban or political history. Renfro’s use of the term “carceral state,” which he never explicitly defines, is also a problem. While its meaning may be self-evident to a certain scholarly cadre, its precise definition is unclear to me. It seems to refer to a combination of the ideas of mass incarceration, state surveillance, and increasingly heavy-handed policies aimed at public safety. Elizabeth Hinton’s similarly excellent From the War on Poverty to The War on Crime (2016) uses the term in this fashion. The use of “carceral” as a descriptor of state confinement originates in Michel Foucault’s Discipline and Punish. Considering its thoroughly malleable source, it should be no surprise that “carceral state” seems to have an amorphous definition.

Though Renfro makes clear his progressive political commitments, Stranger Danger is a book that will have appeal across the ideological spectrum. The governing regime Renfro describes is the shared handiwork of Ronald Reagan, Bill Clinton, George W. Bush, and Joe Biden. Readers on the left will embrace the case Renfro makes for a reprioritization of public spending toward social programs. Conservative and libertarian readers will find the story emblematic of the significant expansion of state power which typically accompanies well-intentioned reform movements.

While Stranger Danger is skeptical about many of the policies adopted in response to child abductions, Renfro shows genuine empathy for the victims of such crimes. This book indicts public policies and the presentation of these cases by activists and members of the media. It never indicts the people who suffered at the hands of others.

Clayton Trutor holds a PhD in US History from Boston College and teaches at Norwich University in Northfield, Vermont. He’d love to hear from you on Twitter: @ClaytonTrutor

Comments