Europe’s Composer

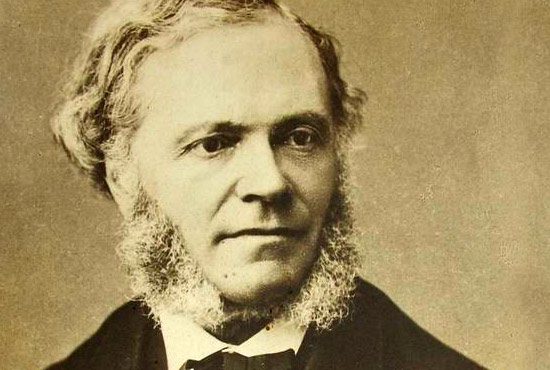

R.J. Stove’s intensively researched biography of Belgian French composer César Franck (1822-1890) has striking merits. Stove writes exquisitely, in periodic sentences, and manages to make detailed discussions of musicology an aesthetic experience for experts and neophytes alike. He also blends his musical discussions with well-told anecdotes, the most appealing of which is his recounting of Franck’s passion for a young beauty with an Irish father, Augusta Mary Anne Holmès.

Because of the erotic excitement this lady generated in Franck, Saint-Saëns, and other musical greats, Mademoiselle Holmès—or, perhaps more accurately, her golden tresses and pneumatic figure—won coveted musical awards as an organist. Her never entirely proven love affair with the middle-aged Franck became the subject of a steamy novel by the author of the screenplay for “The Pianist,” Britain’s Ronald Harwood. Stove constructs this narrative with helpful quotations from Harwood and with just the right mixture of skepticism and racy detail.

Stove scolds with delightful ferocity earlier commentators on Franck and even crosses swords with the long-dead translator of what was once the semi-authoritative Franck biography, by Vincent d’Indy, published in 1906. According to Stove, translator Rosa Newmarch was not only unfaithful to the original but had the chutzpah to put “her own all too often inaccurate sentiments” into d’Indy’s mouth. He offers a similar judgment about another translator of a French biography on which he draws heavily, the work of Léon Vallas, the English edition of which came out in 1955.

The biographies that Stove trusts most are those by d’Indy, Vallas, Joel-Marie Fauquet, English scholar Norman Demuth, and the biographical studies of an obvious personal hero: Franck’s pupil and a composer in his own right, Charles Tournemire (1870–1939). From Stove’s work we learn not only about Franck’s symphonies, extemporized fugues, organ compositions, sonatas, and quartets but also about the composer’s widening circle of acquaintances.

This may be the central point of the biography, even more than Franck’s versatility in producing a wide range of memorable compositions. From his birth in Liège through his studies at the conservatory in Brussels to his long years of residence in Paris, Franck was influenced by and then influenced in turn many of the composers and virtuosi of his musically rich age. Stove already stresses by his choice of titles that he’s as much interested in Franck’s relation to his times as he is in his prolific career. His subject served as a bridge from such romantic composers as Hector Berlioz, Robert Schumann, Franz Liszt, and Richard Wagner to later French composers such as Jules Massenet, Tournemire, Camille Saint-Saëns, Louis Vierne, and Gabriel Urbain Fauré. A younger generation of French composers, known as “la bande à Franck,” sprang up around Franck at the Paris conservatory, where he long taught. Franck attracted other devotees among the students to whom he gave private lessons.

Despite his French nationalism, which took an anti-German turn after the Franco-Prussian War, Franck undoubtedly had Bavarian ancestors, and Stove even suggests that he may have been related to one or more German composers bearing his family name. In any case, Franck knew German and Italian at least as well as French music. And because of his output and his effect on other composers, the contributions of his adopted land to the classical repertoire expanded considerably.

Stove shows convincingly that one of Franck’s quintets served as the basis for a composition by Richard Strauss and how in another case Franck himself may have borrowed from Brahms. The author can sustain these comparisons because Stove is himself a trained musicologist and performing organist, and he understands Franck’s work, especially his organ compositions, on a technical level. This biography’s towering strength is that its author has an in-depth knowledge of Franck’s achievements, and unlike many other biographers of famous composers, Stove painstakingly demonstrates all his musicological assertions. What may annoy his critics is that he holds other biographers to the same standard he sets for himself. Stove is upset that earlier biographer Norman Demuth made certain minor errors in discussing Franck’s life. The author clearly believes that those who came before him and who had more leisure and greater resources to carry out their labors should have been more attentive to facts.

To his credit, Stove takes seriously the scholarship on Franck done by a longtime music-commentator for Le Monde, Joel-Marie Fauquet. Although this embattled commentator has claimed to discern an exhortation for Mussolini’s March on Rome in Berlioz’s operatic adaptation of Virgil’s Aeneid, Les Troyens, and although he elsewhere scolds 19th-century composers for taking patronage from monarchs, Fauquet is a learned and useful biographer, as Stove recognizes. Stove gives him high grades for meticulous research and for editing and publishing Franck’s massive correspondence.

Franck lived in times that saw monumental changes affecting France and its inhabitants. He clearly craved the juste milieu and tried to avoid becoming entangled in the whirlwind around him. Franck was raised with an understandably negative attitude toward the French Revolution, which for his Liégeois parents and grandparents meant being occupied by French revolutionary armies and then being taxed and bereaved of young men for Napoleon’s wars of conquest. Although Franck’s family was not markedly devout, they were practicing Catholics and they may have resented that the Revolution imposed anticlerical laws on the Walloons in what later became southern Belgium.

Soon after Franck relocated to Paris and two days after he married Félicité Desmousseaux, the daughter of a successful actor, the Revolution of 1848 erupted in the French capital. The liberal monarchy of Louis Philippe was overthrown, and after a series of upheavals France fell to the nephew of Napoleon I, Louis Napoleon, who set up the Second French Empire in 1852. Throughout this turmoil Franck kept a low profile and during the Second Empire, which crumbled as a result of the Franco-Prussian War in 1871, he seemed far more occupied with symphonic poems, his position as an organist at Sainte Clotilde church, and his growing family than with taking political stands.

After the disastrous defeat of the French army by German-Prussian forces, the radical Commune was established in Paris in March 1871. Franck was forced to stay even after the Communards had murdered, among other dignitaries, the Bishop of Paris. But the composer remained far from the limelight. He managed to survive the Communards’ rampages and the subsequent bloody quelling of their misrule by the armies of the provisional French government that had been established at nearby Versailles. Franck immediately made his peace with the French Third Republic, which crept into existence in 1874 without a formal proclamation.

Much of Franck’s choral and other music was religious and suitable for performance in churches, though not always in church services. Two of his most renowned works are the symphonic poem “Rédemption” and a poetic, musical rephrasing of the Gospels, “Les Béatitudes” (1870). After Franck’s death in 1890, both of these demanding compositions would be performed with full orchestras, most notably in Belgium and the German Rhineland. In the 1890s, during and after the Dreyfus Affair, France experienced an ugly confrontation between clerical and anti-clerical factions. With the vindication of Dreyfus, the clericals, who bet on the wrong horse, would see their country taken over by the anti-Catholic left. In the ensuing political climate, Franck’s religious music would lose the favor of the French state. Nor, presumably, with the rise of anticlericalism, did it enjoy the popular endorsement in Paris that it had been attained 20 years earlier.

Stove notes in his concluding chapter, on Franck’s “posthumous fortunes,” that his subject became popular internationally after his death. Germans, Englishmen, and Americans began to perform and listen to Franck’s work in ever greater numbers, and in his native Belgium, particularly in Liège, he would be celebrated as a great native son. Stove remarks on the paradoxes attached to Franck’s fame; though someone who identified himself with France, he would posthumously be celebrated in his birth land. Belgium became an independent country in 1831, and as it searched for cultural heroes, both Flemish and Walloon, it turned to Franck, despite the fact that he had lived, died, and been buried in Paris. During World War I, the Allies elevated Franck to “an object of mass ardor,” depicting him as a child of “gallant little Belgium” then being occupied by German troops.

Stove notes in his concluding chapter, on Franck’s “posthumous fortunes,” that his subject became popular internationally after his death. Germans, Englishmen, and Americans began to perform and listen to Franck’s work in ever greater numbers, and in his native Belgium, particularly in Liège, he would be celebrated as a great native son. Stove remarks on the paradoxes attached to Franck’s fame; though someone who identified himself with France, he would posthumously be celebrated in his birth land. Belgium became an independent country in 1831, and as it searched for cultural heroes, both Flemish and Walloon, it turned to Franck, despite the fact that he had lived, died, and been buried in Paris. During World War I, the Allies elevated Franck to “an object of mass ardor,” depicting him as a child of “gallant little Belgium” then being occupied by German troops.

After the war, Franck again achieved stardom in his adopted land, as a French patriot who composed not only religious music—which came back into vogue in post-anticlerical France—but also for the composition “Paris,” produced during the Franco-Prussian War. Despite his appropriation by the victorious Allies, the Germans also continued to play and admire Franck, as a German romantic composer. Indeed, during the Nazi period a biography was written and widely circulated in the German-occupied regions of France with the telling title Cäsar Franck als deutscher Musiker. Stove, who regards Franck as having incorporated the “best elements” of both Teutonic and Gallic music, finds it not at all strange that several European countries should claim his subject. But there is another, less edifying possibility here, namely that political identities are sometimes imposed on artists after their deaths. This illustrious organist, composer, and maître de chapelle at Saint-Clothilde was no exception.

Paul Gottfried is the author, most recently, of Leo Strauss and the Conservative Movement in America: A Critical Appraisal.

Comments