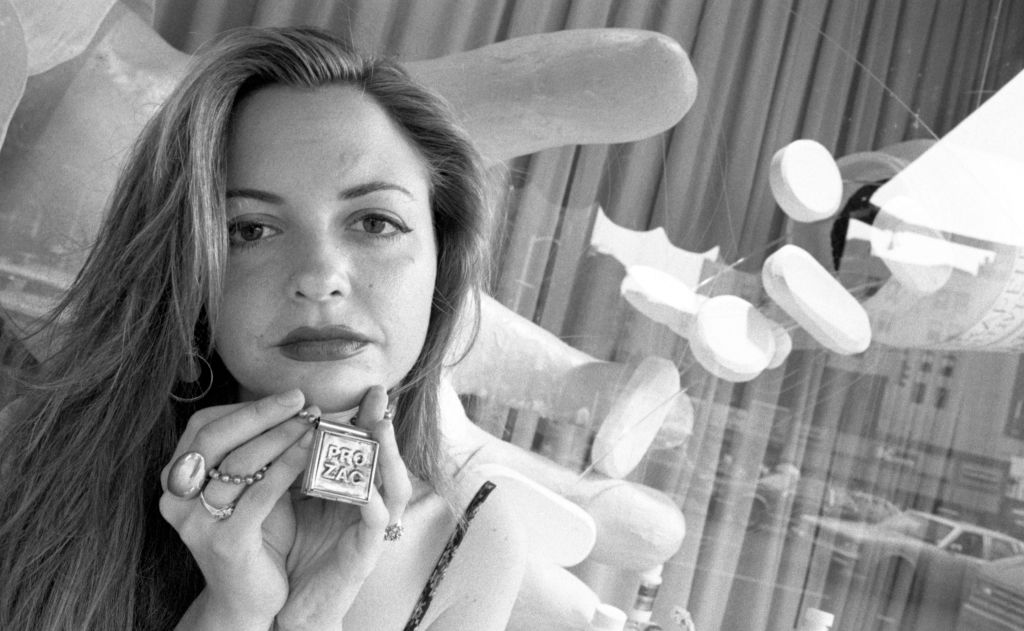

Elizabeth Wurtzel, Trad

Elizabeth Wurtzel died last month. She was the author of Prozac Nation, a memoir both insightful and infuriating, which she published in 1994 when she was only 27. The book is an unflinching tour through the psyche of that most 1990s of types, the depressed child of divorcees, born into “privilege” and staring into the void. It’s also obsessed with itself to an almost unseemly degree, hyper-focusing on the author’s every tic and stumble until all but she can’t help but look away.

Prozac Nation is an account of Wurtzel’s struggle with depression. In its day, it became a kind of canonical text for the depressed, with Wurtzel compared to Sylvia Plath. Wurtzel first overdosed when she was only 12, on antihistamines at a summer camp. She refers to her depression as a “black wave,” and spends much of the book running from it. At each new chapter in her life—college, a move to Texas, a return to New York—she hopes the change in scenery will see it gone for good, only for it to chase her down and swallow her in its shadow. There is no refuge, no glittering Oz where her depression can’t reach. Try though she does, her outward experiences can’t be made to transcend her inner storms.

What’s most surprising is that in commenting on her problems, Wurtzel ends up sounding a lot like a traditionalist. She is the daughter, she says, of the 1960s and the 1980s, two decades whose collision of social liberation and greed, respectively, yielded a generation that prized its own happiness over the wellbeing of its children. Her own parents divorced when she was young. Her mother comes off as a walking conniption fit, constantly melting down over Wurtzel’s issues; her father is far worse, peripatetic and destructive, subtly encouraging her bad habits so he can feel like a free spirit. Wurtzel would lie upstairs and listen to them argue over whose fault it was that she was so screwed up, dark fuel for her despair. More than anything, she says, “I just wanted two parents who both loved me.”

Reading Prozac Nation, you find yourself struggling to draw a line of agency. How much of the havoc that Wurtzel wreaks on her life is her own fault and how much of it can be chalked up to her depression? Certainly about halfway through the book, she stops being sympathetic. When she shows up drunk three hours late to the birthday party her mother throws her, it feels almost like a changing of the guard, a shifting in culpability from her parents to herself. Then again, we perceive this only because Wurtzel doesn’t try to hide it. The strength of Prozac Nation is that it isn’t a Portnoy’s Complaint or even a cry for help so much as an act of gonzo journalism, a voyage into the beat down, fucked up, tilt-a-whirl mind of its protagonist, with nothing spared in what it reports back. Wurtzel can’t be Narcissus before the pool because she hates so much of what she sees. She obsesses over herself because she must know her enemy.

Those reviewers, then, who have tagged her as just another whiny privileged girl—“she went to Harvard!”—are missing the point. Prozac Nation is a reminder that you can grow up with everything and still have nothing. It’s proof that our meritocratic markers of success count for little without inner peace and meaning. Wurtzel is conscious in conveying this message; indeed, in the book’s epilogue, she takes it several steps further. Having at last gotten a handle on her depression through Prozac—she was one of the first patients in the world to try it—she notes that the drug has since gone mainstream. The statistics she provides are sobering: $1.3 billion spent on Prozac prescriptions in 1993, 290 million workdays lost to depression in 1990, those born after 1955 three times as likely as their grandparents to suffer from depression.

Can such an epidemic be merely psychological? She writes:

Perhaps what has come to be placed in the catchall category of depression is really a guardedness, a nervousness, a suspicion about intimacy, any of many perfectly natural reactions to a world that seems to be perilously lacking in the basic guarantees that our parents expected: a marriage that would last, employment that was secure, sex that wasn’t deadly.

This is jarring to read, not because it’s anything radical—such passages are commonplace in Trump-era America—but because it was written 27 years ago. The way Wurtzel characterizes the 1990s throughout Prozac Nation—decaying families, general listlessness, a drug epidemic—makes that decade sound all too similar to today. She even cites a certain politician who declares that we need a new “politics of virtue” and warns of a “sleeping sickness of the soul,” “alienation and despair and hopelessness,” and a “crisis of meaning.” The author of those quotes? Then-first lady Hillary Rodham Clinton.

Today this critique is most often heard from the so-called trads, or traditionalists, who contend that the modern world, by exchanging spiritual fulfillment for material wealth and self-autonomy, has overdosed us on an individualism that’s left us lonely. Or, as Wurtzel put it in 1993, we are suffering from “a low-grade terminal anomie, a sense of alienation or disgust and detachment.” Not that Wurtzel was a true trad, of course. She could be bearable on Twitter, for example, and she didn’t blame a confected Frankenstein ideology called “liberalism” every time she lost her car keys. Her own politics were quite left-liberal. But in making the personal political, in allowing her experiences to inform her views, she nonetheless ended up overlapping with the more reasonable core of their critique.

This “big collective bad mood,” as Wurtzel diagnoses the Prozac frenzy, is not how we remember the 1990s. The Clinton years were supposed to be carefree, all Pogs and pieces of the Aggro Crag, yet somehow America was still choking down antidepressants. How could this be? The parade of culprits is familiar: the breakdown of the family, the addling of ourselves with screens, too much work towards too little telos, declining wages, declining childbearing, declining churchgoing rates. Then there’s the sobering thought that the stats might only capture minor fluctuations in a greater trend, that it’s the human condition to be more or less discontented. The suicide rate, after all, is at a 30-year high, not an all-time peak. The 1990s had Prozac; the 1970s cultural hangover; the 1950s their sense of confinement; the 1930s depression both economic and psychological. Maybe the mistake is in believing we ever had a good temper to lose.

In her third and best book, More, Now, Again, Wurtzel chronicles her drug addiction, which followed her Prozac treatment. And it is one hell of an addiction: for a while, she’s crushing up and snorting 40 Ritalin pills a day. She writes, “Nothing they can do for me will equal the annihilating and totalizing comfort that I get from drugs,” which for her became a hedge against loneliness, “reliable company.” She quits and takes up again, goes to rehab and relapses, gets an abortion and experiences intense sadness. When at last she manages to get clean, it’s with the help of a supporting character who’s rarely acknowledged in Prozac Nation: “I keep begging God for a state of grace. And I thank Him. I thank Him for never giving up on me, even though there were plenty of times I would have been happy to give up on myself.”

Unfortunately that isn’t the end of the story. Seven years ago, Wurtzel penned a piece for New York in which she reflected on her “one-night stand of a life.” Then 44, she lamented, “I live in the chaos of adolescence, even wearing the same pair of 501s,” only to do an about-face and defiantly defend her lifestyle. A couple years later, she married, only to be plunged into the tumult of separation and divorce. God is not Prozac, some kind of smiley-faced cure for our anomie. We can accept him and still feel empty; we can find him and slip right back into the chaos. Wurtzel reminds us that there is at least a little of what we seek that we cannot realize in this world, not through personal ambition, not even through prayer. Her achievement is to make us stare into her unremitting gloom and catch a little more of ourselves than we’re comfortable seeing.

Comments