Breaking Up Isn’t Hard to Do

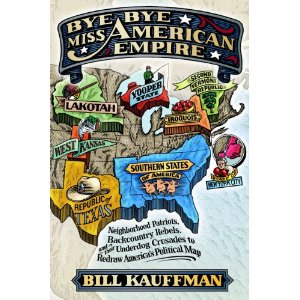

Bye Bye, Miss American Empire: Neighborhood Patriots,

Backcountry Rebels, and Their Underdog Crusades to Redraw

America’s Political Map, Bill Kauffman, Chelsea Green, 336 pages

By Thomas DePietro

Most conservatives want big government in all its bureaucratic remoteness to be shrunk. But few entertain the obvious solution: reduce the number of citizens and the dimension of the places governed. Ridiculously simple? Hopelessly utopian? Bill Kauffman doesn’t think so. And this, his latest work of spirited social criticism, brings to bear all his talents—his historical smarts, his journalistic acumen, his muscular prose—upon his bracing argument for a perennial idea: secession. Let’s break up gigantic states, he says, and let some simply leave the Union. It’s a notion as old as the country itself and as fresh as the recent champions of the Second Vermont Republic, independent New Englanders who hope to bring government back to human scale.

Most conservatives want big government in all its bureaucratic remoteness to be shrunk. But few entertain the obvious solution: reduce the number of citizens and the dimension of the places governed. Ridiculously simple? Hopelessly utopian? Bill Kauffman doesn’t think so. And this, his latest work of spirited social criticism, brings to bear all his talents—his historical smarts, his journalistic acumen, his muscular prose—upon his bracing argument for a perennial idea: secession. Let’s break up gigantic states, he says, and let some simply leave the Union. It’s a notion as old as the country itself and as fresh as the recent champions of the Second Vermont Republic, independent New Englanders who hope to bring government back to human scale.

Kauffman has made an admirable career of celebrating unsung heroes and lost causes. His books include melancholy reflections on the disappearance of small-town life (Dispatches From the Muckdog Gazette); a profound study of America’s localist writers, artists, and thinkers (Look Homeward, America); brilliant accounts of American non-interventionism and antiwar conservatism (America First! and Ain’t My America); and a wonderfully eccentric biography of Luther Martin, the cantankerous anti-Federalist (Forgotten Founder, Drunken Prophet). The last makes clear that Kauffman knows his Founders as well as any scholar of the subject.

By his own admission, Kauffman’s politics are an unusual amalgam of views. A self-described “reactionary radical,” he elsewhere elaborates: “I am an American rebel, a Main Street bohemian, a rural Christian pacifist,” with “strong libertarian and traditional conservative streaks.” His decentralist views give rise to his isolationist sympathies and engender a pantheon of heroes ranging from Dorothy Day and Robert Taft to Gore Vidal and Pat Buchanan. In short, I’ve always thought of him as a party of one. (Or two, since I agree with him on almost everything.)

But Kauffman’s latest book convinces me that he’s not alone in his “front-porch anarchism,” that all over the country movements for smaller, more local government have sprouted and enlisted supporters from across the political spectrum. More often than not, these secessionist groups transcend the tired categories of Right and Left. Yes, Kauffman’s a “beyonder,” as the smug pundits of the Weekly Standard once dismissed those who long for a way out of the conventions of current power politics. But if “beyonder” ideas promise little in the corridors of Washington, D.C., these simple views provide great hope for democratic renewal in the more familiar corners where you live.

History, in Kauffman’s deft retelling, often reminds us of things we too easily forget. In this case, he turns to the question that troubled American politicians almost from the start: “Did the states precede and create the United States without forfeiting their own sovereignty, or, by ratification of the Constitution, did the states subordinate themselves for all time to an indissoluble union of which they are constituent but not independent pieces?” The issue engaged the best minds of the day and soon devolved into the nullification debate of the 1830s—could a given state disregard a federal law, declaring it “null and void?” Kauffman documents the eloquence on both sides, but the real kicker in his account is this little-remarked fact: the first vehement secessionists were not Southerners bent on preserving their right to own human beings. No, the loudest calls for disunion came from the Northern abolitionists, and rightly so. They saw no reason why they should respect the barbarism of slavery. When a slave escaped to their states, they felt no obligation to return him, despite federal laws.

The debate of course turned topsy-turvy with the onset of civil war. Southerners fought for their right to secede (and—let’s not pretend—to preserve slavery) where just a few years earlier the American Anti-Slavery Society in the North had proclaimed “that secession from the United States Government is the duty of every Abolitionist.” Neither prevailed, and Union, which began, in Kauffman’s words, as “a strategic imperative” became in Abraham Lincoln’s “seraphic design” the gospel of the Republic. So much so that even a sophisticated jurist such as Antonin Scalia has argued that the matter of secession was clearly settled once and for all by the Civil War. Might, as it so often does, made right.

Maybe Justice Scalia is correct. Secession may have been a hot topic before the Civil War, as Kauffman’s impressive array of distinguished commentary from the best minds of the time attests. But today, seceding from the United States is surely a pipe dream, entertained only by hippy tree-huggers, gun-toting militiamen, and racist neo-confederates. To be fair, Kauffman does indeed encounter some sketchy characters in his travels among the various groups who champion the decentralist cause. But the majority are nothing like the caricatures—they’re ordinary people who are fed up with unresponsive government at both the federal and state levels. Sounds a bit Tea Party-ish? In that case, Palinistas shouldn’t be surprised that Todd Palin himself once belonged to the Alaskan Independence Party, a group that would rather not share its natural resources and splendors with the confiscatory government of the lower 48.

And what about that other non-contiguous state, Hawaii? In Kauffman’s view, it’s another territory whose acquisition makes sense only in light of the mainland’s endless expansionism, the same creed that leads us into perpetual wars abroad. Not surprisingly, Hawaii too has a history of independence movements that begins almost as soon as it became a state. Kauffman chronicles these populist causes with sympathy for their inspiring leaders and a sense of humor for the absurdities inherent in the struggle.

He spends a lot of time with the articulate and engaging secessionists of the Second Vermont Republic, who have held raucous conventions bringing together communitarians, libertarians, and others who simply love their rural lives. There’s Frank Bryan, a self-described “Vermont Patriot,” with his “defiantly rural populist point of view,” and Thomas Naylor, a former econ professor and theorist of the movement who reminds Kauffman that “Lincoln really did a number on us” by convincing most Americans that is illegal, immoral, and unconstitutional.” Then there’s Kirkpatrick Sale, sometime author of Human Scale, the title of which says it all.

If secession remains an ideal, at least secessionist movements are a step in the right and more attainable direction. Kauffman careens through history, recording the many efforts to break up states that over time have become too big to represent their citizens in any meaningful way. Think of Norman Mailer’s unsuccessful run for mayor of New York in 1969—his platform called for New York City as the 51st state. And others have taken that idea further, with Brooklyn and Staten Island calling for freedom from the city itself. Across the country, Kauffman finds West Kansans trying to split from the eastern part of the state; the rural Upper Peninsula of Michigan hoping to separate from the industrial cities of its south; and Californians admitting that their state has grown out of control, with residents living enormous distances from one another.

Kauffman knows he’s a dreamer, but he’s not the only one. (And there I just imitated Kauffman’s own fondness for appropriating pop lyrics.) Though his opening declaration in Bye Bye, Miss American Empire—“The American Empire is dead”—may be premature, it’s certainly worth hoping with him for its peaceful dissolution, both here and abroad. “Breaking away is impossible,” he concedes, but “so was dancing on the Berlin Wall.” In this punchy and inspirational book, Kauffman proves himself once again a writer fully in the patriotic grain, an American original.

Thomas DePietro is the editor of Conversations With Kingsley Amis. A former contributing editor for Kirkus Reviews, he has written for The Nation, the New York Times Book Review, and Commonweal.

Comments