Bogdanovich’s Masterpiece

Mass media is not inherently bad. During World War II and the decade that followed, Hollywood, pressured by the Production Code and its own executives’ rather old-fashioned mores, consistently churned out films and TV shows that presented middle-class America as an ideal as enchanting as, but more attainable than, Merrie England. Those who went to see Meet Me in St. Louis or stayed up to watch My Three Sons went to bed dreaming of picket fences and meatloaf dinners.

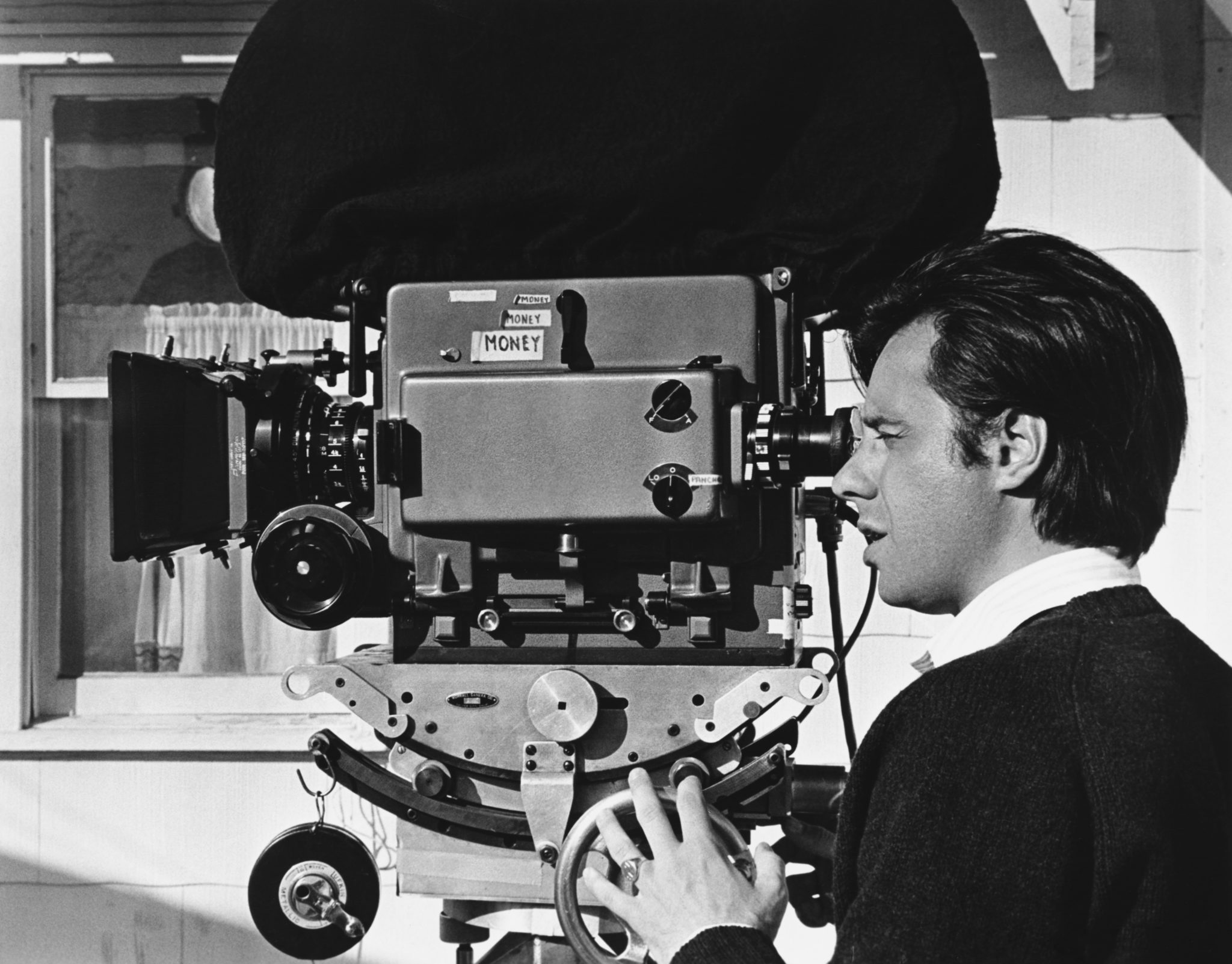

But even as Hollywood was still doing lip service to the idea of hearth and home, there were forces at work that were cleaving actual hearths and actual homes: neglectful parenting, poor economic prospects, a surplus of free time and a deficit of productive things to do. Such is the state of affairs shown in Peter Bogdanovich’s masterpiece The Last Picture Show.

Columbia Pictures released The Last Picture Show to near-unanimous critical and popular enthusiasm in the autumn of 1971. Newsweek said that no film by a young American director had been as good since Orson Welles made Citizen Kane; it received eight Oscar nominations and two wins.

Based on one of the best early novels by the late Larry McMurtry, who co-wrote the screenplay with Bogdanovich, The Last Picture Show tells of the largely lonely and lovelorn inhabitants of Anarene, Texas, in the early 1950s, including high-school classmates Sonny Crawford (Timothy Bottoms), Duane Jackson (Jeff Bridges), and Jacy Farrow (Cybill Shepherd), as well as their assorted parents, teachers, and minders. Anarene is a small town in a frontier state, and the 1950s was a period that most of us would judge more innocent and upright than our own. Yet with the benefit of hindsight, Bogdanovich discerned a chasm between the middle-class ideals promoted by Hollywood and the reality on the ground in Anarene.

Not that Bogdanovich had anything against Hollywood. As a film historian, magazine journalist, and interviewer of pioneer filmmakers, Bogdanovich had persuasively argued that the Golden Age of Hollywood wound down around the time of John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance in 1962 and that much of what followed was decadent or trivial. He once suggested that color and sound were superfluous additions to cinema in its purest state. (The Last Picture Show’s rich, contrast-y black-and-white cinematography is by the great Robert Surtees.)

In his capacity as artist rather than film buff, Bogdanovich was wise enough to recognize that even the best movies, even those as good as Liberty Valance, can’t carry the load for a society that has otherwise given up on itself. The Last Picture Show is set during a time of cultural riches—the movies were good, the TV shows wholesome, the songs by Hank Williams and Tony Bennett tuneful and not too lurid—but civilization itself is shown to be utterly threadbare. We see the movie theater, pool hall, and café, but we only get a few looks at the school and nary a glimpse of a church or a courthouse or a city hall.

“An audience doesn’t know the geography of a place unless you show it to them,” Howard Hawks told Bogdanovich during one of their interviews. “If you don’t show them, it can be anything you want it to be.” Anarene, as Bogdanovich shows it to us, is a town in which the physical infrastructure is shoddy, trashy, crumbling.

It’s also depopulated, so empty of background extras that at times it looks like the “after” shots in one of those nuclear test movies. The grownups in Anarene have mostly gone AWOL. Sonny’s pop is all but invisible, while Jacy’s mother and father lead lives not of quiet desperation but of palpable, persistent regret. Shiftlessness is rampant. People drive from place to place, amble about the streets, and, once in a while, go to the movies.

Ah, the movies. Not long after we first meet him, Sonny joins a bunch of teenagers for an evening at the Royal, the town’s ramshackle, single-screen movie theater, to see that week’s “picture show,” Vincente Minnelli’s 1950 romantic comedy Father of the Bride, starring Elizabeth Taylor as a dewy-eyed bride-to-be and Spencer Tracy as her bewildered but understanding father. In the 1970s, Bogdanovich said he chose Father of the Bride strictly as a counterpoint. “I wanted as big a contrast to the lives of those kids in that small town in Texas as possible, and nothing could be a bigger contrast than a sort of Hollywood version of middle-class America.”

What are the kids thinking as they watch Liz up there on the silver screen, dreamily eating a dish of ice cream? Perhaps they recognize the gap between their existence and hers. Then again, maybe they don’t; movies, even more than literature, invite identification, making every moviegoer a would-be king, soldier, or debutante. At the Royal that night, Sonny motions for his girlfriend Charlene (Sharon Taggart) to accompany him to the back row, where they can make out with impunity. “Guess what? It’s our anniversary,” Charlene announces. “We’ve been going steady a year tonight.” Later, the two fool around more intensely in the privacy of Sonny’s truck. Charlene, declining his more forward advances, is suddenly overcome by respectability: Sonny should suppress his ardor until the two are married, which Charlene, unaware that her beau already has eyes for well-heeled golden girl Jacy, takes as a fait accompli.

That Charlene frames her sad, tawdry encounters with Sonny in terms of an “anniversary” and a future marriage suggests that the more genteel attitudes of movies like Father of the Bride managed to trickle down to the lower orders. This is true even in the film’s most taboo-violating relationship, Sonny’s subsequent intense, confused affair with Ruth Popper (Oscar winner Cloris Leachman), the sickly, sad-sack spouse of his coach. Indeed, Bogdanovich, a cinematic classicist par excellence, films these dalliances with lyricism and poetry. At one point, in the sort of shot one would be apt to encounter in one of Warner Brothers’ great women’s pictures, Bogdanovich shoots Sonny and Ruth’s fulsome embrace from outside, and then through, a front window of Ruth’s house. Sonny might as well be the sailor returned home from war, Ruth the loving bride back home.

Using this sort of classical style, Bogdanovich isn’t being ironic but simply conferring dignity on characters who lead imperfect lives yet have an inkling of what proper behavior looks like. Even Jacy, after she strips down for a nude swimming party, has second thoughts when the wristwatch she is wearing stops after hitting the water. (Bogdanovich, who in the 1980s aligned himself with the anti-pornography feminists Andrea Dworkin and Catharine A. MacKinnon, later said he regretted including nudity in this scene, but he must be given credit for subtly grieving Jacy’s loss of innocence.)

The teenagers in The Last Picture Show are guided by the half-digested romanticism of the movies they see and their own carnal instincts, an admixture sure to result in arguments, breakups, reunions, pregnancies, shotgun marriages, and overall despair. McMurtry’s sequels, which imagine happier endings for some of these characters, never fully convince. Yet Sonny and Duane, at least, are not completely unmoored. The boys in town gravitate towards Sam the Lion (Ben Johnson), the owner of the aforementioned movie theater, pool hall, and café, and, more significantly, “the film’s teacher, law-giver, fount of values,” in the words of film writer Peter Biskind.

As played by Johnson, a fixture in John Ford’s Westerns, Sam the Lion is Jimmy Stewart, Gary Cooper, and Will Rogers all rolled into one. At one point, Sonny and Duane foolishly help arrange an encounter between a slightly dim younger boy, Billy (Sam Bottoms), and a portly prostitute, Jimmie Sue—a nightmarish sequence that ends with Billy’s nose having been bloodied and Jimmie Sue, lurching towards the camera in a grotesque Wellesian close-up, crudely insisting, “Wouldn’t mess with him again for less than three-and-a-half.” When Sam the Lion learns of this shameful episode, he speaks forcefully. “I’ve been around that trashy behavior all my life,” he says with the sort of grizzled firmness that earned Johnson an Oscar. “I’m getting tired of puttin’ up with it.”

Yet one tough-talking father figure does not a young man make. Even after Sam the Lion’s admonition, Sonny and Duane still make a tequila-fueled sally to Mexico and brawl with each other over who will win the hand of Jacy. Bogdanovich is no scold. He soaks in Sam the Lion’s moralizing, but he perceives the teenagers’ underlying humanity even while condemning their outward behavior. In taking up with Ruth, Sonny is not trying to violate society’s unwritten laws but is expressing a measure of sympathy with a wayward soul. By the same token, Jacy, who has her own series of painful, ill-judged romantic encounters with those her age and older, is merely, to paraphrase Lillian Gish in The Night of the Hunter, looking for love in her own foolish way.

Yet one tough-talking father figure does not a young man make. Even after Sam the Lion’s admonition, Sonny and Duane still make a tequila-fueled sally to Mexico and brawl with each other over who will win the hand of Jacy. Bogdanovich is no scold. He soaks in Sam the Lion’s moralizing, but he perceives the teenagers’ underlying humanity even while condemning their outward behavior. In taking up with Ruth, Sonny is not trying to violate society’s unwritten laws but is expressing a measure of sympathy with a wayward soul. By the same token, Jacy, who has her own series of painful, ill-judged romantic encounters with those her age and older, is merely, to paraphrase Lillian Gish in The Night of the Hunter, looking for love in her own foolish way.

At the climax of the film, Sonny and Duane turn out for one last picture show at the Royal: Howard Hawks’s great Western Red River. Sam the Lion has since gone to his maker, and doddering Miss Mosey, to whom he has willed the theater, is shutting the place down. So Sonny and Duane take it all in: John Wayne, the cattle drive, the yeehaw-ing cowboys, Dimitri Tiomkin’s score. Bogdanovich the film buff celebrates Red River for its vitality and excitement; Bogdanovich the sociologist understands how little Red River can do—for these kids, in this town, at this moment. The second the house lights come up, the spirit of intrepid Western expansionism evaporates. There are realities to be faced: Duane will serve his country in Korea, Sonny will attempt a rapprochement with Ruth.

The Last Picture Show is not only as unremittingly bleak as any great film ever made in America—far bleaker than the confections Bogdanovich later specialized in, including the marvelous comedies What’s Up, Doc?, Paper Moon, and They All Laughed—but also startlingly prescient. Here is a film made 50 years ago, diagnosing the state of a small town 20 years before then, that speaks to the condition of today’s youth. Just switch out a few details: Instead of going to the movies, Sonny and Duane would be on YouTube or Xbox Live. Jacy would be addicted to Instagram; Sonny and Duane to opioids or marijuana. The movies they might encounter wouldn’t even pretend that there was a better, nobler world out there—no Liz Taylor, no John Wayne. Not that Liz or the Duke ever did the citizens of Anarene much good anyway.

Peter Tonguette, who writes regularly for the Wall Street Journal and Washington Examiner, is the author of a recent book on Peter Bogdanovich.

Comments