Blight & Flight: The Wisdom of Abandoned Buildings

I have mixed feelings about the removal of unsavory aspects of our history for the same reason that I am ambivalent about tearing down old motels and strip malls; because our built landscape, complete with its failures and its blight, provides a wealth of knowledge into how to live and not to live, into the mistakes and successes of different eras of development.

In a wistful passage of Nineteen Eighty-Four, Winston Smith stumbles into an old antique store and browses the merchandise: a serious crime in his society. He finds an old record player and a beautiful paperweight. The Party, Winston muses, established its totalitarian hegemony not just by burning books and executing dissidents; it did so also by continually rewriting history and purging it of such things as filled the antique store: unique, interesting, beautiful things, things unmistakably pointing to a very different period of human civilization and thus suggesting the possibility of a very different way of life. When life is experienced as one dismal extended present moment, when people are not aware of their place in time and history, it is much easier to establish control over them. Orwell, of course, wrote this thinking of Soviet communism. It also uncannily describes life under modern American consumer capitalism.

There is therefore something political—something conservative—about preserving, or at least documenting, seemingly quotidian things like the appearance and merchandise of old department stores and motel rooms, or the history of now-abandoned retail stores and their neighborhoods.

In addition to formal historians and historic preservationists, there is another group of people who understand this. There is no name for them, exactly—they are a combination of urban geographers and urban explorers. They are hobbyists who photograph and document the history of abandoned or repurposed buildings, often piecing together the old geographical reach of forgotten chain stores or gleaning insights about the changes in certain retail industries or in the layout of neighborhoods.

And there is much to learn from them, even if they are no longer useful in our capitalist economy.

Many old retail locations show a familiar pattern of a kind of reverse-gentrification: they begin as department stores, turn into discount stores, and end up as dollar stores or immigrant-run ethnic shops. As the buildings decay, the process can look like creeping blight, but the transformation of old retail sites into immigrant enclaves also has its upsides. As buildings age and rents decline, they can provide cheap space for immigrants to start businesses, thus beginning their climb into the American middle class.

Other lessons are less obvious, and are only revealed through modern archaeological sleuthing. For example, one discovers that a surprising number of drug stores actually inhabit former supermarkets. This is because the average size of a supermarket has tripled or quadrupled since midcentury. This is about more than just construction preferences; it is yet another piece of evidence of the “supersizing” of American consumer life.

Sometimes abandoned places reveal the flaws of infrastructure design. There are the famous cases of freeways bisecting neighborhoods and interstates bypassing smaller state and county roads. But this can happen on a much smaller scale; after a ramp was built to bypass a circle in Somerville, New Jersey, several businesses on the circle lost traffic and shuttered, leading to the blighting of the area for years. The decaying former businesses are only now in the process of being replaced. They demonstrate the destructive effects of our automobile-first infrastructure.

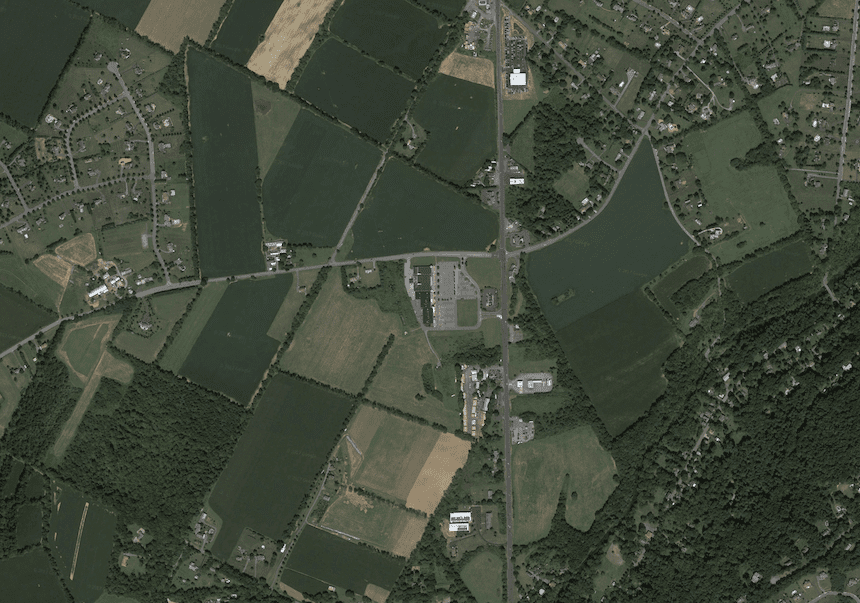

Urban geography also reveals the limits of suburban and exurban growth. A massive A&P in Washington, New Jersey tells a story of suburban development gone haywire. The A&P was built in the 1990s to serve the far edges of the New York suburbs, which had reached all the way out to the Pennsylvania/New Jersey Lehigh Valley in those years of post-Gulf War gas prices and Ford Expeditions. The people who moved there to work in New York could expect a commute upwards of two hours. The A&P and most of its accompanying strip stand empty now, fatally undermined by the 2008 financial crisis. How many marriages were broken by such a lifestyle? How much drudgery and misery does that empty store, and the McMansions amid the farm fields, testify to? Unless it is remembered before it is all razed and grown over, we will lose this cautionary tale.

Studying the history of everyday buildings also simply teaches us what our own communities used to be, which may seem quaint but is a useful exercise in our age of rootlessness. One might think that no particular effort at preservation—at least in memory—is necessary, given the ability of the Internet to remember almost everything, almost automatically. Yet despite the Internet’s ability to ferret out everybody’s nude pictures, it can be wickedly difficult to discover the physical history of a place without actually living there and knowing the old-timers or local newspapermen.

But most of all, the shells of our once-thriving malls and shops can teach us humility. They can make us feel small. Learning from them is less about placing blame than about recognizing a truth: society does not exist by right. It is not automatic. We tend to believe, if we think about it at all, that our way of living is the default; it isn’t. Humans may be imbued with a spark of divinity, but that does not mean that our societies are exempt from the laws of nature. Our cultures in all their richness are still ultimately underpinned by the ability to survive and make a living.

Consider that most famous exemplar of abandonment, Detroit. Looking at entire blocks of what were once houses, now forests with a stray fire hydrant peeking out from the underbrush; surveying the hulking, empty ruins of theaters and factories, churches and police stations; seeing hospitals with defibrillators and radiology machines still sitting in examination rooms as if everyone simply left one evening and never came back; one feels viscerally that a great crime, a crime against civilization itself, must have been committed here.

Yet it is also the hard, inevitable reality of what happens when the bottom falls out of an economy. Trade protections and tax incentives might prevent this some of the time. But sometimes, it just happens. Ants abandon tunnels; wasps abandon nests; humans abandon strip malls and factories. In a biological-anthropological sense, what is a city if not a massive ant colony?

The lesson to learn from this is not that humans are unexceptional, or that economic determinism rules the day. It is that human civilization is both uniquely beautiful and uniquely fragile, and therefore uniquely worth preserving.

Addison Del Mastro is assistant editor for The American Conservative. He tweets at @ad_mastro.

Comments