Beyond Trump vs. Trump: We Have a Nation to Safeguard

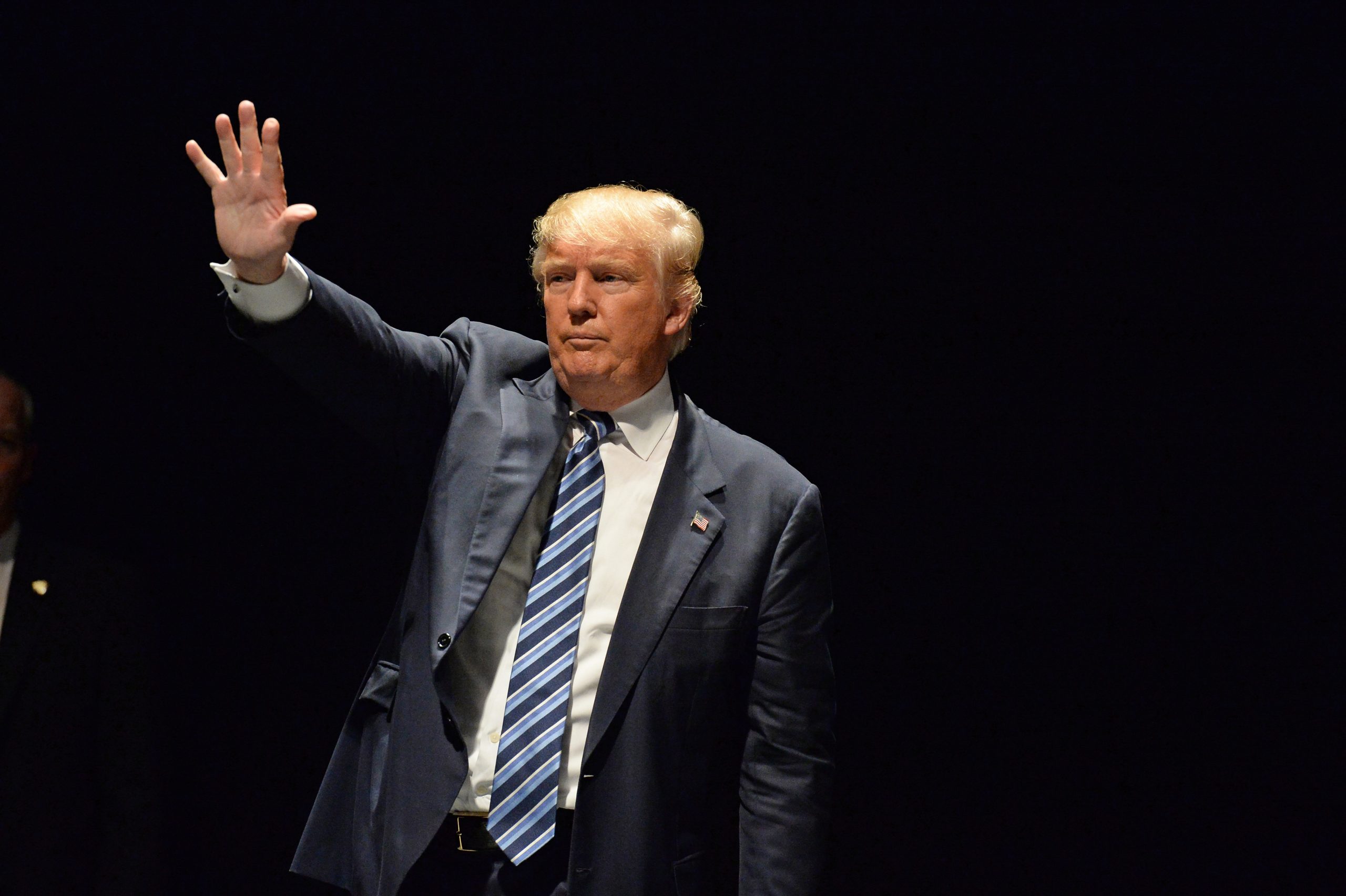

President Trump is obviously not happy about about the highly unflattering portrait of him painted by his niece, Mary Trump, in her best-selling book, Too Much and Never Enough: How My Family Created the World’s Most Dangerous Man.

On July 17, reacting to her description of him as “narcissistic,” “dysfunctional,” and “perverted,” the president jabbed back in a tweet, describing her as “a seldom seen niece who knows little about me, says untruthful things about my wonderful parents (who couldn’t stand her!) and me.”

Of course, the Main Stream Media loves the new book; indeed, pressies are always careful to insert that Mary Trump is a “clinical psychologist,” thereby seeking to assign greater weight to her judgment on the famous uncle; she’s not just an estranged family member, she’s a trained clinician. Thus when Mary declares that Donald’s “pathologies are so complex and his behaviors so often inexplicable that coming up with an accurate and comprehensive diagnosis would require a full battery of psychological and neuropsychological tests that he’ll never sit for”—the MSM treats her words as the voice of an oracular psycho-authority.

Indeed, speaking of long-distance diagnosis, it might be small comfort to the 45th president to know that plenty of other American presidents have been similarly psychoanalyzed. In fact, no less than the father of psychoanalysis himself, Sigmund Freud, co-authored an unsparing assessment of our 28th president, Thomas Woodrow Wilson: A Psychological Study.

Moreover, we’ve learned, over the last century or so, that the mind of any individual, when perceived though the Freudian prism, appears to be nothing more than a heaving mass of Greek-named complexes and phobias. And yet through it all, most people manage to get off the couch and do things, including becoming politicians—a very few even becoming president of the United States. So how do they manage that? And what does that mean for the rest of us?

Some enduring answers to such questions can be found in Harold Lasswell’s 1930 book, Psychopathology and Politics. Lasswell is obscure now, but in his day, he was a professor at Yale Law School as well as president of the American Political Science Association. Moreover, he was active when Freud was at the peak of his influence; Psychopathology and Politics is much shaped along the contours of the Viennese Herr Doktor’s thought.

Evidently realizing that the word “psychopathology” in the title would send a strong signal, Lasswell opened his book, a bit defensively, with the declaration, “The purpose of this venture is not to prove that politicians are ‘insane.’” In fact, Lasswell, being mostly a political scientist, was careful to stipulate that “the specifically pathological is of secondary importance to the central problem of exhibiting the developmental profile of different types of public characters.” In other words, for all his fascination with individual minds, in the end, the author was actually most interested in collective political outcomes.

For purposes of analysis, Lasswell categorized three types of political personality: the “agitator,” the “administrator,” and the “theorist.” To illustrate this triptych, Lasswell named a few names; Herbert Hoover, for instance, was labeled an administrator, while Old Testament prophets were labeled as agitators, and Karl Marx labeled as a theorist. Interestingly, Vladimir Lenin was listed as all three types.

Still, for the most part, Lasswell chose to focus, in the Freudian clinical style, on anonymized exemplars of each political personality type, detailing the mental circuities of “Mr. A,” as well as “B,” “C,” and so on.

From there, Lasswell considers how each type meshes with politics. As he puts it, the state is a “manifold,” into which political figures enter, and through which political events “are to be understood.”

He writes, “political movements derive their vitality from the displacement of private affects upon public objects.” Using dark Freudian terminology, Lasswell asserts that “Political crises are complicated by the concurrent reactivation of specific primitive impulses.” In that same bleak spirit, he also avers, “Politics is the process by which the irrational bases of society are brought out into the open.”

Yet while phrases such as “primitive impulses” and “irrational bases” are the stuff of psychiatry, Lasswell also wrote in political science-y language, as when he laid out his equation for political action: p } d } r = P. Here, p stands for “private motives,” } stands for “transformed into,” d equals “displacement on to public objects,” r stands for “rationalization in terms of public interest,” and P “signifies the political man.”

In Lasswell’s formula, individuals bring their personality with them into the political arena, and then, if they wish to make a mark in politics, they must reconcile, somehow, their own personalities with the political environment. As Lasswell explains, “The distinctive mark of the homo politicus is the rationalization of the displacement in terms of public interests.”

We might note that in no sense was Lasswell saying that homo politicus was necessarily good-hearted, or that people were always wise about their own well-being; as he put it, oftentimes, “people are poor judges of their own interests.” And so the “solution” in politics, he continued, is “not the ‘rationally best’ one,” but rather, “the emotionally satisfactory one.”

Still, Lasswell did not believe in autocracy or dictatorship; he approvingly quoted another political scientist who argued, “Society is not safe . . . when it is forced to follow the dictations of one individual.”

Yet because Lasswell shared Freud’s gloomy view of human nature, he argued for a sort of guided system, dubbing it “preventive politics.” As he put it, “The politics of prevention draws attention squarely to the central problem of reducing the level of strain and maladaptation in society.” Thus Lasswell endorsed the application of therapeutic psychology to the population as a whole—putting the country, as it were, on the therapist’s couch.

If that doesn’t sound like a plausible solution, we might note that we often do just that to our country’s leaders—and the latest instance is what Mary Trump has done to her uncle.

Yet even those who mistrust a long-distance diagnosis—and who might see Mary Trump’s book as opportunistically timed to the election—might nonetheless reflect on Lasswell’s political equation, p } d } r = P.

After all, individuals do enter into the political system, and they do what they do—and so it’s best if we understand them as well as we can. Indeed, each new entry can be seen as a case study, providing us with an opportunity to learn: What went right? Or, what went wrong? And who makes a good leader?

Such cumulative study gives us all a chance to practice a Lasswellian “politics of prevention.” That is, while we don’t seem to be able to cure the mentally ill, we can nevertheless take sterner measures to keep the pathological out of political office, especially high political office.

In particular, we might take the view that the electoral political system should serve as a kind of filter, separating out the gold from the dross. If, as Max Weber put it, politics is “the slow boring of hard boards,” then maybe we should favor politicians who actually know how to drill a hole, and who know to drill it in the right place—and not smash the board.

Indeed, if we think of prosaic electoral politics as a filtering process, we might gain more respect for those who prove themselves in a minor office before seeking a major office—and major responsibility. To put the matter bluntly, if a wannabe pol is maladaptive, let’s know early on, when the stakes are low.

This wisdom was well expressed by Sam Rayburn, the Texas politician who served in the U.S. House of Representatives for 48 years, as well as in the Texas state house for six years before that—and, remarkably, rose to be speaker in both chambers, in Austin as well as in Washington, D.C. As recorded in David Halberstam’s classic book about the origins of America’s fiasco in the Vietnam War, The Best and the Brightest, in 1961, then-Vice President Lyndon B. Johnson gushed to his old pal Rayburn about how smart and impressive were the men of John F. Kennedy’s administration, bandying about brilliant ideas for saving the world. To which Rayburn responded to LBJ, “You may be right and they may be every bit as intelligent as you say, but I’d feel a whole lot better about them if just one of them had run for sheriff once.”

In other words, it would be better if the soaring kites of their intellects were tethered to mundane human experience and political reality—including the reality of running for office. As we know, absent such tethering, those best and brightest led us into an Asian quagmire, drowning even the political career of LBJ.

So now, in 2020, in these extraordinarily trying times, the voters are about to run their political filter yet again. Indeed, if the presidential polls are to be believed, this filtration system is favoring Joe Biden, who has, after all, undergone the “extreme vetting” of a half-century in elective politics. (Update: Commenter “Mother124” makes a good point: Maybe the vetting of Biden hasn’t been extreme enough, in light of various unresolved questions swirling around the candidate and his family. So hopefully, more vetting of Biden will take places in the months to come, perhaps along the lines of Politico’s harsh examination of his Delaware milieux.)

So is this an instance in which Lasswell’s idea of “preventive politics” is being applied? We can never know from the Yale professor himself, of course, since he long ago went to that great ivory tower in the sky. Yet still, one senses that the author of Psychopathology and Politics would be pleased.

Because, after all, the fate of the nation is more important than the strange case of Trump vs. Trump.

Comments