Are Conservatives Reforming Criminal Justice?

“Why Conservatives Turned Against Mass Incarceration.” That’s the subtitle of a new book, Prison Break, and a related panel last week at the American Enterprise Institute. The first word speaks volumes: the issue isn’t “whether” but rather “why” the right joined the justice-reform movement.

“Today’s conservative positions could not be more different” from those of the 1980s and 1990s, reiterated Steven M. Teles, a coauthor of the book, during the event. A flyer even referred to the “conservative-led prison reform movement.”

There’s some truth to these claims. Over the past decade, conservative intellectuals have put together a compelling case for reducing incarceration, and they have had some success promoting their agenda to red-state governments. But contrary to the popular narrative, their arguments have not yet won the day with everyday conservatives or even with many legislators. In fact, measured by opinion polls and changes in state imprisonment rates, liberals are still decisively leading on this issue.

Certainly there are good reasons to roll back our most punitive policies. As conservative reformers note, the U.S. imprisonment rate has grown dramatically since the late 1970s—a trend that began as an understandable and effective reaction to high crime but that continued past the point of diminishing returns.

These reformers eschew the throw-open-the-prison-gates mentality of some on the left. “You have to realize that the crime problem was real—and still is real in many regards—and it’s completely irresponsible to talk about this issue without talking about the crime problem,” said Vikrant P. Reddy of the Charles Koch Institute, one of the leading conservative reformers (and a TAC contributor) at the AEI event. Instead, Reddy and his allies champion a suite of cautious, moderate reforms, and they root their arguments in conservative principles such as a distrust of government power, a desire to reduce spending, and sometimes a religious belief in redemption.

This phenomenon—prominent conservatives taking up what was long seen as a liberal cause—yields the heartwarming story of a “bipartisan consensus” we can celebrate and whose “why” we can explore. Pointing to significant reforms in Texas, of all places, conservatives can even brag about “leading” the charge for reduced incarceration. But much is left out of this narrative, some of which emerged at the event last week.

Naturally, there was a designated critic of the reform consensus there: Heather Mac Donald of the Manhattan Institute, who, while lauding the desire to find alternatives to prison, challenged the idea that we can release many current prisoners without threatening public safety. (Disclosure: Mac Donald advised me during a journalism fellowship I held in 2009.)

But there was also the deeper question of whether a consensus really exists. During a Q&A session, Paul Mirengoff of the blog Power Line noted a federal sentencing-reform bill that has struggled to win the support of congressional Republicans. In response, David Dagan, Prison Break’s other coauthor, advanced the theory that it’s actually easier to fix sentencing in deep-red states than at the federal level because one-party control opens up “space” for reform.

To flesh out the story of which states are changing their approach to punishment and who exactly is supporting this trend, I looked at nationwide opinion and imprisonment data. Let’s start with Americans in general: do they want to cut sentences?

It depends how you ask the question. The ACLU, for example, recently found that 69 percent of Americans agree it’s important to reduce the prison population. By contrast, the General Social Survey (GSS) routinely asks people if they think the courts in the area are “too harsh,” “not harsh enough,” or “about right” in their treatment of criminals. In 2014, a solid majority—63 percent—went with “not harsh enough.” That’s progress of a sort: from the 1970s through the mid-’90s, the number was almost always above 80 percent.

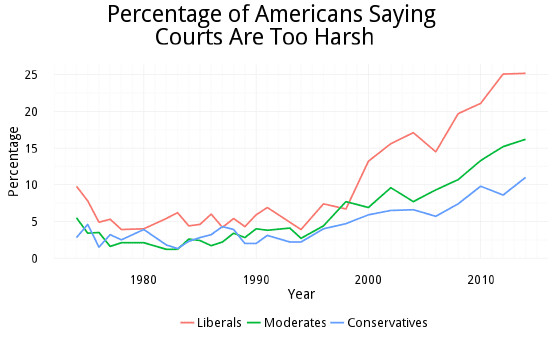

What both surveys show is an enormous political gap. In the ACLU poll, 81 percent of Democrats but only 54 percent of Republicans wanted to reduce the prison population. And here’s what I got when I looked up the percentage of conservatives, moderates, and liberals who thought their local courts were “too harsh” over decades’ worth of GSS data:

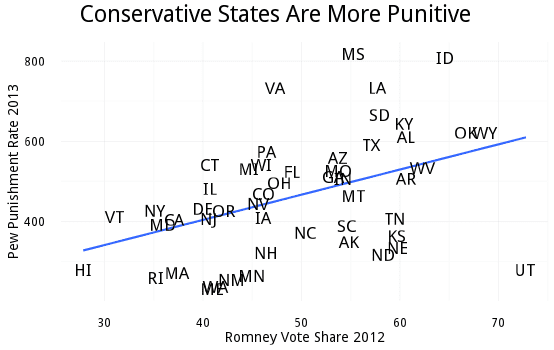

What about state governments? We often hear, for example, that Texas reduced its prison population without increasing crime, thanks to an effort that began about a decade ago. That’s true and praiseworthy, but in 2013 Texas still had the tenth-highest “punishment rate”—a measure of incarceration from the Pew Research Center that takes crime into account—in the nation. This is reflective of a broader trend: red states tended to be considerably more punitive than blue states by Pew’s reckoning, as we can see by matching the organization’s punishment rates with the percentage of voters who supported Mitt Romney in 2012:

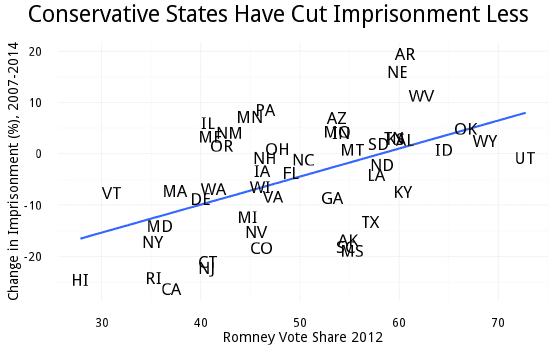

Maybe this just reflects the lingering effects of decades-old decisions to incarcerate more. At least red states are reducing their incarceration rates faster, right? Actually, blue states also tended to have steeper drops in imprisonment rates between 2007 (when Texas began its reform efforts and the national rate stopped rising) and 2014 (the most recent year available). The work of Reddy and company is visible in the fact that some of the more punitive red states are the ones where incarceration is declining the most, but these states swim against the tide.

Reformers know there’s a lot of work to do, and they know their progress is fragile. Prison Break itself notes that incarceration rates remain high in some states that have enacted reform, and it concludes with a chapter that dives into the obstacles to further measures.

But these are the first two sentences of that chapter:

Twenty years ago, no one would have predicted that conservatives would move so far in rethinking their tough-on-crime position. Without this shift, the significant reforms in some of the nation’s reddest states would have been impossible, and there would be much less room for progress at the federal level, or even in blue states.

Conservatives’ shift has been less dramatic than those words suggest—and blue states may not need the example of red-state reforms.

Robert VerBruggen is managing editor of The American Conservative. Twitter: @RAVerBruggen

Comments