A Nonpolitical Mann?

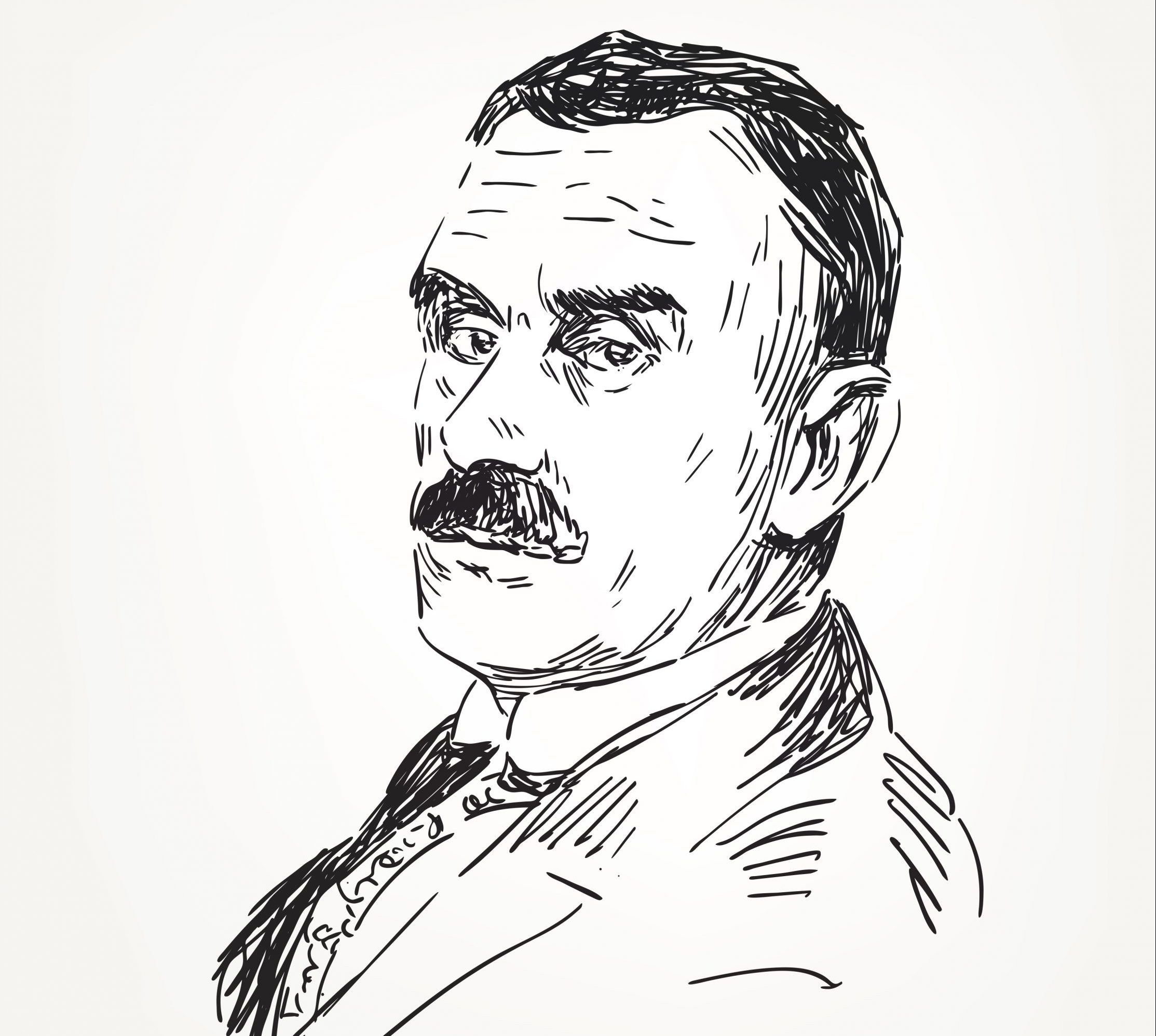

Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man, by Thomas Mann, trans. Walter D. Morris, (New York Review Books: 2021), 592 pages.

Everyone knows the name Immanuel Kant. What’s even more tragic is that hardly anyone knows the name Johann Georg Hamann. At various points in Kant’s career, Hamann was an intimate friend and a strident critic—often at the same time. He couldn’t help admiring Kant’s gigantic brain (a temptation that becomes easier to resist as the centuries wear on), but Hamann found his whole Enlightenment project impious, hypocritical, and not a little absurd.

The Enlightenment sought to free mankind from his primordial ignorance, his childish superstition. Fair enough, thought Hamann. But Kant and his chums would not, Hamann feared, liberate mankind. They would only enslave him to a new, even more terrible master.

At its best, Thomas Mann’s 1918 manifesto Reflections of a Nonpolitical Man stands firmly in the reactionary tradition of Hamann. But here Mann is seldom at his best.

This book was, I think, meant to be a defense of the German cause in World War I. If so, any right-thinking Kraut would have skimmed Mann’s tome and promptly surrendered to the Allies. Mann claims that the war was the latest attempt by the “Latins” to break the German peoples. Caesar tried to subjugate the barbarian tribes; the Catholic Church tried to suppress Luther; Napoleon tried to destroy the Holy Roman Empire. They’re all just different acts of the same drama.

According to Mann, the Latin world stands for universal subjugation to a set of abstract laws and dogmas. Germany, meanwhile, is protestant with a little “P.” Germans, and only Germans, have resisted the Latin leviathan at every turn. (Apparently, Mann had never heard of Scotland.) The war between the Germans and the Latins was a war between “intellect and politics,” “culture and civilization,” “soul and society,” “freedom and voting rights,” “art and literature.”

There’s some truth to that theory, and Mann almost gets around to defending it. The trouble is that it’s the most poorly written book I’ve ever come across. Mann fills the thing up with quotations from, and analyses of, his own novels. Every third sentence takes the form of a rhetorical question. He lays on the sarcasm so thick I could never really tell when he was being serious and when he was just sneering. I’ve never encountered a book stuffed with so much superfluous nonsense—and I’m a big Melville fan. Clocking in at 500 pages, I feel confident that a good editor could have chopped these Reflections down to 150 without losing anything of value.

“This book is a constant digressing,” Mann protests. “That lies in its nature.” Alas.

One gets the distinct impression of watching the author work out his ideas on the page. After making his bold case for German militarism and accusing German liberals of conspiring with the allies against the Reich, he suddenly declares that “artistry, the gypsy spirit, and libertinism make up the suprapolitical part of human nature, the part not consumed by the state and society.” Ah, says the reader. He’s not a reactionary. He’s just a hipster.

Sure enough, about forty pages later, he confesses: “My independence is that of a Bohemian”—which is perfectly obvious to us long before it dawns on Mann.

Really Mann belongs to the class of avant-garde artists and intellectuals who flourished in the interwar period who despised the decadence, daintiness, and bloodlessness of modern civilization. They craved the vitality of raw power, of great souls, indomitable wills. Little wonder that Mann calls Nietzsche his “master.”

Richard Wagner, another of Mann’s heroes, was one such “vitalist.” So was W.B. Yeats, the poet and occultist who had monkey testicles grafted into his body, hoping it would increase his potency. So were Ezra Pound, Gabriele D’Annunzio, and Julius Evola. And so was Charles Maurras.

Maurras, founder of the right-wing party Action Française, is the political thinker whom Mann most resembles. Both were hopeless aesthetes who prized art above all. Maurras was a stylish little man and a self-professed Epicurean. He went deaf as a boy but considered it a blessing: every time he heard Gregorian chant or a Mozart sonata, he would be moved to tears, which embarrassed him.

This is how Mann summarizes his own politics, or anti-politics:

I want the monarchy. I want a tolerably independent government, because it alone guarantees political freedom, both in the intellectual and economic spheres. I want it because it was the separation of monarchical state government from the monied interests that gave the Germans leadership in social policy. I do not want the parliamentary and party economic system that caused the pollution of all national life with politics… I want objectivity, order, and decency.

Maurras would have roundly agreed. He spoke of his ideal as the dictateur et roi: the dictator-king. Meanwhile, his enemies—the philosophers, journalists, and parliamentarians—he dismissed as ancilla plutocratiae: the handmaids of plutocracy.

Mann and Maurras were also both atheists who nevertheless believed that Christianity served a useful political purpose. “I know that it would be incomparably easier for me to believe in God than in ‘mankind,’” Mann huffed. “For putting aside whether the individual person can be good without God, it is absolutely certain that the masses of people will never find the slightest reason to be good without the belief in God.”

Maurras felt the same way. He called himself a positivist, after Auguste Comte, and derided the Gospels as having been written by “four obscure Jews.” Yet, following World War I, he emerged as France’s most strident defender of political power for the Church. Maurras wrote in his manifesto that, under his regime, “Roman Catholicism, France’s traditional religion, would be restored to all the honors to which it is entitled.” Why? Because “Catholic political thought rejects revolutionary ideology.” No thanks to those obscure Jews, I’m sure.

At the height of Maurras’s popularity, Pope Pius XI placed his books on the Index of Forbidden Books and forbade Catholics from associating themselves with Action Française. The Holy Father (wisely, in my view) wasn’t keen on having some atheist who scorned Christ’s teachings and openly used the Church to his own political advantage serve as Catholicism’s de facto spokesman in France.

(Apropos nothing, in 2017, a French diplomat told reporters that Steve Bannon had referred to Maurras as his “guru.”)

Men like Mann and Maurras were not real monarchists, Christians, or reactionaries. They didn’t love authority so much as power. They didn’t admire any ancient regime; they just hated the modern world. Mann approvingly quotes Wagner as saying that, in “an absolute king…the concept of freedom is elevated to the highest, God-filled consciousness, and the people are only free when one man rules, not when many rule.” Now, that man could be another Charlemagne; he could just as easily be someone like Hitler.

And, eventually, it was Hitler. On the eve of World War II, virtually all of these “vitalists” sided with the Axis Powers. They dropped Christian monarchy like yesterday’s newspaper and embraced what António de Oliveira Salazar called “pagan Caesarism.” Meanwhile, true reactionaries like G.K. Chesterton, T.S. Eliot, and Salazar himself aligned with the Allies against fascism. Claus von Stauffenberg, the chief conspirator behind Operation Valkyrie, was a Catholic and a monarchist.

As for Mann, as soon as war broke out, he dropped the right altogether, declared himself a liberal democrat, bolted for the United States, and toured America rallying support for an invasion of his homeland.

That’s Mann at his worst. As I read his Reflections, I kept thinking of another train wreck of a manifesto written by an otherwise talented author: Oscar Wilde’s “The Soul of Man Under Socialism.” Both are overwrought, precocious, and completely divorced from reality. The obvious antitheses would be Eliot and Orwell: celebrated writers who were also serious political thinkers in their own right.

Wilde’s failure is that—well, he’s Oscar Wilde. Mann’s is that, by the time he decided to play-act as a nationalist, he’d been steeped too long in the European intelligentsia. This is the fellow who wrote in the beginning of his book, “Nothing could be more French than the confused mixture of venomous slander and fancy rhetorical pride,” before going on to quote a truly nauseating amount of French literature, French philosophy, French opera, French newspapers, and French aphorisms—all in the original French, of course.

Every once in a while, this self-loathing Francophile will forget himself and accidentally return to the thesis of his book: the nonpolitical man, the hatred of politics. As it happens, I just finished writing a book called The Reactionary Mind. I define “reactionary” as one who rejects the Politicization of Everything, a process that predates the Enlightenment but which came to fruition in the French Revolution. On this point, Mann and I agree. Deep down, I think he was one of us.

For instance, in one of these random outbursts, Mann says the liberal regime is “evil, abstract, inhuman, and therefore very boring.” Whatever else you want to say about democracy, it’s an absolute yawn.

It’s so boring, in fact, that Fox News has to trap its viewers with leggy blonde anchors. CNN has to scare its audience into coming back day after day by churning out endless conspiracies about Russian agents in the White House. The nonpolitical man—the reactionary—would be glad to simply tune out.

Mann recounts one episode so exquisite I have to quote it at length. He recalls sharing a cab with some party activist on election-day. The driver is a young man, working class, and wears a wedding ring on his finger. It’s raining.

The politico jumps in and sits next to Mann,

his hat pushed back on his head, with wild eyes and flushed cheeks, starting to talk while he is still on the steps. He is going full steam, in a political rage. He has come from the polls, an agent probably, a recruiter, a vote-chaser, at any rate a fiery party man. He cannot be quiet; one sees it; his heart is full of politics and half-education, and half-educated, excited street talk pours endlessly from him. He is speaking to no one and to all of us.

Mann concludes that this politico

is the very distortion of the nation, and I remember well the look with which the driver finally turned towards the embarrassing man and eyed him from head to toe, this sober, quiet-unfriendly, deprecating, slightly disgusted look of the man in the service coat at the one who was drunk with politics and half education.

The politico is the middle-aged man in the MAGA hat who accosts you for wearing a facemask in public. He’s the elderly woman in the vagina hat who accosts you for not wearing a facemask in public. They’re embarrassing, contemptible, and unbearably boring.

The driver, meanwhile, is the silent majority that stands ready to sock the next person who talks about facemasks, or Donald Trump, or Joe Biden, or Sean Hannity’s or John Oliver’s outrage-of-the-day.

The driver, meanwhile, is the silent majority that stands ready to sock the next person who talks about facemasks, or Donald Trump, or Joe Biden, or Sean Hannity’s or John Oliver’s outrage-of-the-day.

Mann says that politics has become “an atmosphere, permeating all vital air so that with every breath drawn it forms the main element of all psychological structure.” We think in political terms. We can’t help it. We can’t stop, even if we want to—and most of us really do want to.

Isn’t that the essence of totalitarianism? When even the very air we breathe is saturated with ideology? When the citizen’s relationship to the state forms his very “psychological structure”?

I agree with Reginald Jeeves, that consummate reactionary, that Nietzsche is “fundamentally unsound.” Yet no sane person can help but agree with his recommendation, as quoted by Mann, that we “avoid reading newspapers every day or even serving a party.” That’s how we become nonpolitical men. It’s a feat Thomas Mann himself never quite managed, though not for lack of trying.

Michael Warren Davis is author of The Reactionary Mind, forthcoming from Regnery.

Comments