How to Start a Retail Business Without a Main Street

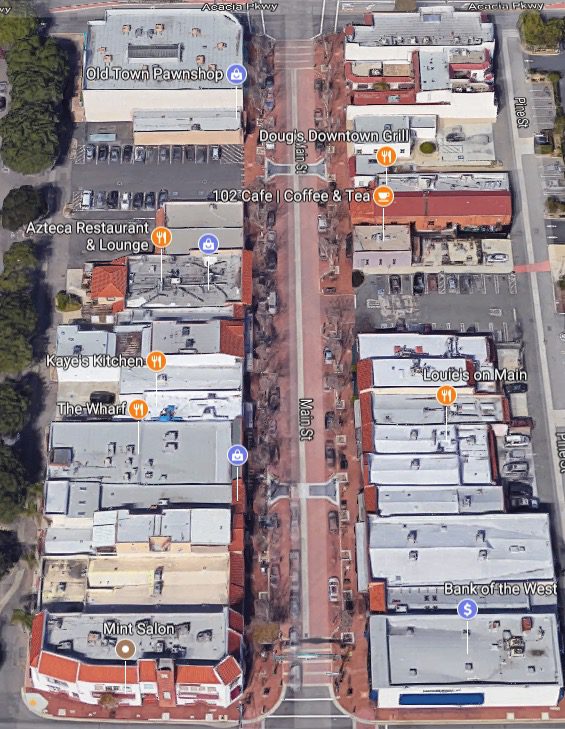

This is the historic Main Street in Garden Grove, California. Back in 1874 land was platted in small twenty-five foot wide lots and sold off with minimal infrastructure. Individuals built modest pragmatic structures with funds pulled largely from the household budget, extended family, and short-term debt. This was long before the thirty-year mortgage, government loan guarantees, mortgage interest tax deductions, zoning regulations, subsidies, economic development grants, or the codes we have today.

Many of these simple one-story shops were specifically designed to be subdivided in to two smaller shops that were each about 12 feet wide and not terribly deep. These were ideal economic incubators with a low bar to entry for tenants, yet they generated a high yield per square foot for the landlord. Businesses could expand and contract as needs changed. Some things failed. Others succeeded. Time sorted it all out.

Many of these simple one-story shops were specifically designed to be subdivided in to two smaller shops that were each about 12 feet wide and not terribly deep. These were ideal economic incubators with a low bar to entry for tenants, yet they generated a high yield per square foot for the landlord. Businesses could expand and contract as needs changed. Some things failed. Others succeeded. Time sorted it all out.

Families often lived above their own shops. In many cases, rooms or apartments were rented to tenants. Sometimes the upper floors served as professional offices or hotel rooms. This was an additional layer of flexibility that allowed properties to adapt over time while providing affordable yet profitable accommodations. Everything expanded gradually as money and market demand permitted. This was the process that produced our Main Street towns all across the country.

Here’s an aerial view of Main Street courtesy of Google. At one time it was the economic and cultural center of a thriving farm community. Notice the amount of private value relative to public infrastructure.

Let’s pull out a bit and see what the surroundings look like today.

Whatever may have existed around Main Street is now a vast ocean of surface parking lots. Next door and across the street are big box stores along high speed arterial roads. Times change. When transportation switched from shoe leather and horses to cars and trucks the scale of absolutely everything in society ramped up exponentially. Then the old Main Street became a relic.

Garden Grove’s civic leaders obviously thought its historic center was worth preserving, so planners did the best they could to keep it viable. Removing defunct buildings in favor of parking lots made the shops available to suburban motorists.

Decorative paving, ye olde lamp posts, hanging flower baskets, park benches, lots and lots of American flags, potted shrubbery, and piped in music created a respectable unified atmosphere for retail. The place is clean, safe, and orderly.

Events are programmed to keep Main Street active and attract customers: an Elvis festival, a vintage car show, the annual celebration of the strawberry. Shops that might otherwise go empty are filled with civic organizations like the Chamber of Commerce and the offices of elected representatives. Garden Grove’s remaining historic center—all one block of it—is well maintained. But it stopped functioning as a town a long time ago. It’s now an embellished strip mall. The current regulatory environment and larger economic context have halted the iterative wealth building process that might have otherwise continued. Now it’s dependent on city planning efforts to keep up appearances with grants for fresh lipstick and rouge. It’s an exercise in sentimentality and kitsch. Nothing else is legal anymore.

Advocates for a return to the kind of development pattern that existed a century ago are up against hard limits of every kind. Reforming the current system of regulations and cultural attitudes is a waste of time. What they don’t recognize is that the small scale, fine grained, mom and pop process is alive and well in places like Garden Grove. It just doesn’t look like a Norman Rockwell village. That era is gone and isn’t coming back anytime soon. But a new version is already here. The mobile shop is the new version. I see more and more of these all across the country, because this is the new low resistance entry point for small businesses to form.

This is only the visible stuff. Inside many suburban homes are businesses that you can’t see. These aren’t traditional retail stores. Operating a physical shop makes no sense in most cases. Who can compete with Costco or Amazon? Who wants to try to extract permission from the zoning authorities? But household ventures generate income in ways that aren’t readily apparent from the curb. I can’t publish photos of the best examples because I’d get a lot of good people into trouble. But trust me. They’re out there in large numbers under the radar.

When it comes to housing it’s incredibly difficult to build anything simple and cost effective anymore. A combination of endless regulations and outraged neighbors means only production home builders are left in the game. They build whole subdivisions of single family homes, or they build two hundred unit apartment complexes. The middle range of modest accommodations is no longer a reasonable option. Under the circumstance the existing stock of suburban homes are pressed in to service as de facto multifamily buildings. On my way out of Orange County I asked a waitress at the airport about her living arrangements. She said she rented shared space in a five-bedroom house in Costa Mesa. The overall rent was $4,200 a month. Her share was $1,100. She had three room mates. She also had three kids. That’s why so many front lawns are parking lots.

I have a peculiar ability to wander around and get myself invited in to people’s lives. This place in Garden Grove was once a little 1950s tract home. It was added on to in a way that perfectly conformed to all the existing rules and procedures and is still a fully detached single family home.

But individual rooms are rented out and the tenants share a common kitchen and baths. It’s a small apartment building by other means. This is what we get when we forbid the Norman Rockwell Main Street model. Some people hate it. I see it as a perfectly natural response to the artificial constraints that have been placed on the old Main Street model.

We can’t go back. But we can adapt and move forward under the circumstances.

John Sanphillippo is an amateur architecture buff with a passionate interest in where and how we all live and occupy the landscape. He blogs at Granola Shotgun, where this post originally appeared. New Urbs is supported by a grant from the Richard H. Driehaus Foundation.

Comments