The Story Of Which We Are A Part

I’ve always got several books going, and yesterday I added one more to the mix: Alexandria, the forthcoming novel from Paul Kingsnorth (will be published on October 20; pre-order here.) I love Kingsnorth’s essays — read some of them here — and have become e-mail friends with him since he wrote me earlier this year after commenting on this blog. He’s an Englishman who lives in rural Ireland. He arranged for his publisher to send me an advance copy of Alexandria; it arrived yesterday. I started reading it at once, and though it’s a little hard to get into, I’m hooked now.

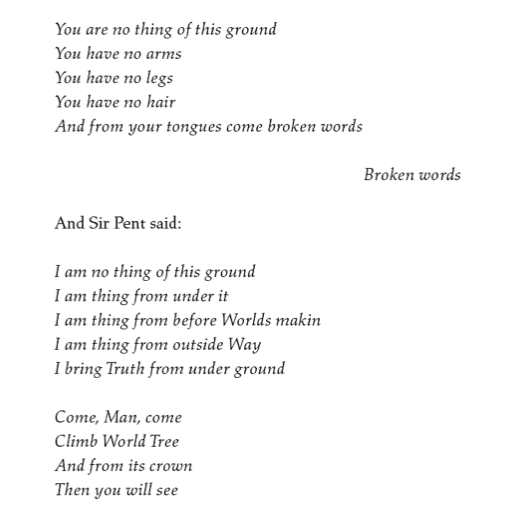

It’s set far into the post-apocalyptic future, among a small community of people living in the fens of east England. They are primitive; we don’t know the nature of the apocalypse that befell the Earth in time out of mind. They have created a natural religion to help them make sense of their world — a story of which they are a part. What made this book a little difficult for me to get into was Kingsnorth’s experimental prose. He is imagining the way people living under those circumstances would talk, having only received the English language, and standard English spelling, in a fragmentary way after the apocalypse.The brokenness of their sentences and spelling is a sign of the severity of the collapse. Here’s an excerpt:

I was struggling with this style until I read it out loud, as an experiment — then everything clicked. Kingsnorth writes like a bard.

Here is the Fall of Man myth that the people of this community hold. Notice how it’s the same one from Genesis — a serpent seducing man — but they have no memory of the Bible.

Get that? The tempter comes as as one who will expose the Way as a lie, as a construct of power that prevents Man from realizing that He is actually a god. He is the bodiless exposer of the Way as a lie meant to keep Man down. Note that in this mythology, the fact that Sir Pent doesn’t have a body is indicative of his nature as a Deceiver. Somehow, I believe, as this book unfolds, we are going to learn that the mythology that these people live by derives from their experience living with bodies in the world.

These people have a prophet, an old man who dreams. They regard birds as sacred, and as carrying portents for them. Early in the book — I’m only 35 pages in — he foretells the return of swans, which no one alive has ever seen. These are the first glimpses the reader gets of the story that this isolated community of survivors lives by.

Anyway, the book is fascinating. Once you get used to its style, it’s like reading documents from an ancient world, though this one far into the future.

It brought to mind a famous line of Alasdair MacIntyre’s:

I’ve been thinking about this quote this weekend, actually. On Saturday, I participated in a small Zoom discussion of Live Not By Lies that an old friend organized. One of the participants mentioned that it’s a shame that so many people were so willing to abandon churchgoing in Covidtide. I told him that I disagree — and that my take on the topic was determined in part by realizing that the story of which I find myself a part is the story of Christian prisoners of conscience in the Soviet bloc. (I didn’t put it like that, but that’s what I was saying.)

I explained that I found myself less freaked out by the Covid restrictions on churchgoing than many of my Christian friends did. I couldn’t quite understand it, until I thought about it, and realized how deeply I had absorbed the accounts of Christians who survived communist prisons.

One of the best books I read in my Live Not By Lies research is the prison memoir of Silvester Krcmery (pronounced “kirch-MERRY”). I have an English translation published in Bratislava under the title This Saved Us: How To Survive Brainwashing. It was later published in the US under the more anodyne title Break Point. Whoever holds the copyright to this book, I beg you to bring it back into print now that Dr. Krcmery is a key figure in a new American bestseller. This book is absolute gold.

In it, Dr. Krcmery, who was thrown into a communist prison in Slovakia for his Christian faith, talks in detail about the things he did to withstand torture, interrogation, and imprisonment. Among his strategies: never feel sorry for yourself. Think of the time in prison as an opportunity to do penance. Think of yourself as “God’s probe” — there to learn spiritually and morally, so that you can help others. With the normal Christian life taken away from you, establish prayer disciplines within the confines of your new reality. Offer your suffering as a gift to God, for the sake of others who suffer. Meditate on your life and on all those you know and love. Think about Scripture. Pray. Pray. Pray.

How small our sacrifices seem when compared to what Christians like Dr. Krcmery, and countless others, had to endure at the hands of communist torturers and jailers! Nevertheless, they were and are real sacrifices. Krcmery teaches us how to approach this trial. I’m also reminded — and I’ll post on this tomorrow, in a separate context — of something a friend told me about recently: the Stockdale Paradox. It’s something that the heroic prisoner of war Admiral James Stockdale once said, about those who survived captivity in Vietnam, and those who didn’t. The optimists were the ones who died of heartbreak, Stockdale said — the ones who kept telling themselves things like, “We’ll be home by Christmas!” The ones who survived were those who held onto hope that they would eventually prevail, but who did not fortify themselves with the false promises of optimism.

So it is with us Christians during Covidtide. The story of which we find ourselves a part did not include suffering, not really. That’s why we have been so cold-cocked by the Covid plague: this kind of suffering has not been in our experience. We didn’t imagine that it could happen to us. But here it is. Now it is time for us to realize that what happened to Dr. Krcmery, and all the other prisoners of conscience, really is part of our own stories as Christians. And because these men and women learned first-hand what it means to suffer well, with sanctity and integrity, they share that with us, so we can make it a real part of our own chapter in the Christian story stretching around the world, and back two millennia.

What if Covidtide has been a severe mercy from God, a gift given to prepare us for a much worse trial to come? In Live Not By Lies, I quote Dr. Krcmery (d. 2013) saying:

We live, contented and safe, with the idea that in a civilized country, in the mostly cultured and democratic environment of our times, such a coercive regime is impossible. We forget that in unstable countries, a certain political structure can lead to indoctrination and terror, where individual elements and stages of brainwashing are already implemented. This, at first, is quite inconspicuous. However, often in a very short time, it can develop into a full undemocratic totalitarian system.

Dr. Krcmery was ready for the harshness of communist prison because his spiritual father, the priest Tomislav Kolakovic, had prepared him and the others in their fellowship. Now Dr. Krcmery, Father Kolakovic, and the others are offering to us their stories, for the sake of our own preparation. If you have absorbed these stories as I have, you will not be rattled by this Covid trial of church closures, because you know that it can get much, much worse, and that we Christians absolutely need to prepare ourselves internally and communally for a time when we may not be able to go to church at all, and not because of a virus. Let the reader understand.

One more quote from the Krcmery part of Live Not By Lies:

“Memorizing texts from the New Testament proved to be an excellent preparation for critical times and imprisonment,” he writes. “The most beautiful and important texts which mankind has from God contain apriceless treasure which ‘moth and decay cannot destroy, and thieves break in and steal’ (Matthew 6:19).”

Committing Scripture to memory formed a strong basis for prison life, the doctor found.

“Indeed, as one’s spiritual life intensifies, things become clearer and the essence of God is more easily understood,” he writes. “Sometimes one word, or a single sentence from Scripture is enough to fill a person with a special light. An insight or new meaning is revealed and penetrates one’s inner being and remains there for weeks or months at a time.”

Dr. Krcmery did not want to be in prison, heaven knows. But the communists didn’t give him a choice in he matter. His spiritual preparation ahead of time (including memorizing Scripture for a time when he could not have a Bible), and his fundamental attitude of there being nothing greater than the opportunity to lay down his life for God, made all the difference. It will for us too, under our much less harsh but still burdensome circumstances.

We will only know what we are to do when faced with trials if we first know the story of which we find ourselves a part. Our story as the Church on a pilgrimage through time is also the story of martyrs and confessors. They offer us priceless wisdom that we now need to understand how to be steadfast in the face of trials that we cannot escape, but only endure. Mere optimism will be the spiritual death of us. We need hope.

For most of us, our story as Americans and as American Christians, has been one of freedom, stability, and prosperity. Of course black Christians have a very different narrative (I hope a black Christian writes a Live Not By Lies or a Benedict Option based on the black church’s historical experience), and other religious believers (Catholics, Mormons, etc) have found themselves persecuted at times. For most of us, at most times, our story is one of peace and plenty. As Dr. Krcmery, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and other dissidents testify, this can all disappear faster than you think. If our story as Christians does not make a central place for suffering as a normative part of the Christian experience, then we are not going to make it through this coming trial. American believers who have only ever been taught that peace, plenty, and religious liberty are normal will experience the loss of these things as a falsification of the Christian story. Those who know better, they stand a better chance of coming through with their faith intact.

I’m going back to Alexandria now, to see how Kingsnorth’s fictional tribe finds the hope and meaning they need to endure their trials. Stories like this can sometimes become part of our story too. Kingsnorth’s terse retelling of the Fall of Man myth helps me understand the actual Fall better. The second part of the myth involves Man climbing into the crown of the World Tree, and the serpent binding him there in pain and terror for nine days, before letting him fall back to the ground. I am quite eager to see where Kingsnorth takes his characters, and me, his reader.

Subscribe for as little as $5/mo to start commenting on Rod’s blog.