The Chinese Embassy’s Embarrassing New Address

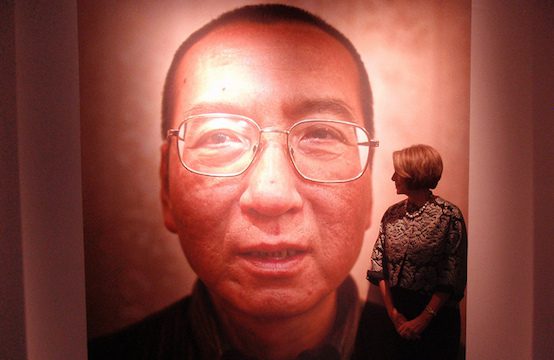

Chinese dissident and human rights activist Liu Xiaobo has a habit of making headlines from prison. The political reformer began his fourth prison term, this time an eleven-year sentence for “subversion,” in 2009, only to receive the Nobel Peace Prize in 2010, and now a surprising congressional move has pulled him into the most local of politics. Last week, the House Appropriations Committee approved an amendment to next year’s budget that would rename the address of the Chinese embassy in northwest D.C. to “1 Liu Xiaobo Plaza” in his honor.

David Keyes of the nonprofit Advancing Human Rights explained the position of the move’s bipartisan advocates when the proposal was initially made. As he tells it, the idea is to remind other countries that their domestic policy decisions have an international cost: “Every time the representatives of tyranny walk outside of their offices, they should be confronted with the faces and names of those whose freedom they deny. Dissidents languishing in prison must know that they are not forgotten.”

Washington street names have been political arenas before. Similar motivations led Congress to rename the address of the Soviet embassy “1 Andrei Sakharov Plaza” after a Soviet dissident and human rights activist in 1984.

Criticism from China on this latest move was to be expected: a spokeswoman from their Ministry of Foreign Affairs called the proposal a “complete farce,” while online commenters proposed renaming the address of the U.S. embassy in Beijing after Edward Snowden. But Americans are faulting the move as well. Richard Bush of the Brookings Institution, for instance, complained that the renaming’s “symbolic shaming” would not accomplish much. “Of course, what the regime did to Liu Xiaobo violated every reasonable moral standard, and this action will make some in the West feel good. But it will not speed his release by even one day.”

Yet no one questions that the move is anything other than symbolic. The proposal’s sponsor, outgoing Virginia Rep. Frank Wolf, defended the move in moral language: “Renaming the street would send a clear and powerful message that the United States remains vigilant and resolute in its commitment to safeguard human rights around the globe.” The question is not whether the U.S. can force China to release Liu Xiaobo by renaming a street. Secretary of State John Kerry has already made the U.S. position on Liu’s case perfectly clear in the past. Rather, Wolf’s message-sending may be aimed in another direction entirely.

Human rights advocacy has taken a back seat as an American foreign policy priority in dealing with China. Taken in that context, the street sign proposal may be sending a message to Americans, rather than the Chinese. Naming the street of the Chinese embassy after a jailed dissident may be a small effort to suggest to Americans that human rights should be a bigger national priority. It is that agenda that should be debated, not the overdramatized foreign policy implications of a street sign.

Comments