Master and Commander on the Far Side of the Galaxy

I still can’t make up my mind what to think about Paul Thomas Anderson’s new film, which I saw last night. Not that I’m not sure it was a great film – I know what I think of it. I’m just not sure what I think about it.

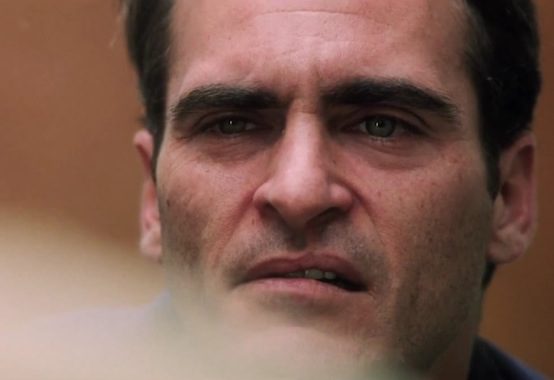

First things first: yes, I saw it in 70mm. Film snobs everywhere are arguing about whether this choice was brilliant or pointless, but from my perspective the significance of the choice was simply that it made it possible for the film to be really big. And there’s something about monumentality in and of itself. Vir Heroicus Sublimis really doesn’t look like much at all, unless you’re up close and personal. See? So, similarly, a close-up of Joaquin Phoenix’s curled lip is one thing, but when his face is the size of Jefferson’s on Mount Rushmore, a curl of the lip feels like it heralds the collapse of civilization.

On the other hand, precisely because of the impact of sheer scale, I’m second-guessing my initial awed reaction. How much of that was a reaction to the movie as a movie, as opposed to the experience of it as an overwhelming fact?

On yet a third hand, maybe experiencing an overwhelming fact has the right to be, you know, overwhelming. And this movie is chock full of overwhelming experience, overwhelming images and overwhelming performances.

But let me backtrack a bit. What is this movie about?

Well, that’s a good question. Ostensibly, it’s about a kind of therapy cult loosely modeled on the early years of Scientology. A man, Freddy Quell (Joaquin Phoenix), suffering from shell-shock layered on top of a more deeply disordered personality, bounces from one job to another amid the abundance of late-40s America. Fleeing his latest disastrous human encounter, he stows away on board a ship in San Francisco where a party is going on, only to discover, the next morning, that the ship is skippered by Lancaster Dodd (Philip Seymour Hoffman), a self-described “writer, a doctor, a nuclear physicist, a theoretical philosopher” and, incidentally, the founder of a novel form of therapy, known as “The Cause” (the movie’s counterpart to Dianetics). Dodd takes an instant shine to Freddy, and so begins Freddy’s journey into the inner circle of the cult, and into a movingly affectionate relationship with Dodd.

But Anderson doesn’t really have any interest in cults, what leads someone to found one, or join one, and has even less interest in Scientology specifically. You would expect that a movie about a cult would show the titular Master to have a profound psychological hold on his followers, but this is not the case in “The Master.” Virtually every member of the cult, from the socialite who lends Dodd the boat, to another socialite from Philadelphia who is puzzled by changes introduced in “book two” of Dodd’s works, to Dodd’s son, who believes his father is making everything up, to another follower who declares that “book two” stinks, and should have been a pamphlet – virtually everybody involved in “The Cause” seems to be perfectly lucid and, moreover, perfectly willing to be critical of Dodd, at least out of his earshot. Not very cult-like.

Moreover, the principal character of the movie is so deeply strange, so “aberrated” in Dodd’s words, that we think, at first, what we’re going to see is one man’s search for a cure for his intolerable condition. This could certainly make for an interesting movie. Quell is an alcoholic, like his father. His mother’s a schizophrenic. He’s addicted to “potions” made from antifreeze and photographic chemicals and God-knows what else (Dodd’s initial bond with Quell is based on enthusiasm for those potions). He’s disturbed sexually, seeing genitalia in a series of Rorschach blots, confessing to Dodd that he had sexual intercourse repeatedly with his aunt, having simulated intercourse with a sand woman he creates at the beach and (in one of the most striking visual sequences of the film), stripping the clothes from all the women at a party in his mind’s eye, turning the scene into a kind of cocktail party sur l’herbe. And yet he’s plainly terrified of actual sexual encounter. So he’s got “issues,” as they say, and this could be a movie about how he overcomes them.

But, of course, Anderson doesn’t believe for an instant that a crackpot system like “The Cause” could possibly provide such a cure. And the various forms of “processing” that Dodd puts Quell through don’t obviously improve his condition at all. So . . . what then?

The movie came together, for me, in a scene, somewhere in the middle, when Dodd and Quell are placed in adjoining cells in a Philadelphia jail, Dodd for embezzling funds from a rich socialite’s charity, Quell for scuffling with the cops when they came to arrest Dodd. The screen is split down the middle by the bars between their respective cells. Hoffman stands on his side, his hand resting with an almost Mannerist delicacy, observing as Phoenix erupts in furious rage, smashing his head and shoulders on the underside of the upper bunk, pulverizing the latrine with blows from his foot, shredding his shirt and the legs of his pants and writhing like a panther in a straight jacket.

And then Dodd says something like, “this fear of being confined has been with you for millions of years; it was implanted in you by an invading force” – and Quell interrupts, cursing, accusing Dodd of making it all up, and the two men commence cursing at each other. Quell throws in Dodd’s face that his son has no respect for him; Dodd retorts that nobody likes Quell, nobody at all, “except me. I’m the only one who likes you.” And, though he goes on to say, “and I’m done with you,” they both begin to calm down, and the next time we see them together, free, they are rolling on the lawn, laughing in each other’s arms, like father and son.

That bond between surrogate fathers and sons has been Anderson’s principal emotional interest since “Boogie Nights,” and the shared loneliness of these two men is the powerful core of the film. And this film would have been a strong one if it was just about that bond, and how it warps their relationships with everybody else. That’s the movie that Amy Adams, who plays Dodd’s wife, Peggy, is in. She is powerfully jealous of Quell and her husband’s love for him, which is obviously deeper than his love for her, and his need for him, which is a warmer thing. Peggy is the kind of strong woman they say is behind every great man, who believes in her husband more than he does and hates his enemies more than he does, but Adams gives us a very clear idea of just what a horrible job that is to have in a marriage, and just how ugly is Dodd’s need for her, a need for her to be exactly this ugly person that he can then dismiss as too extreme, not enlightened as he is. Right after the nude party of Quell’s fantasy (and, by the way, Adams’s facial expression in that one scene deserves an Oscar all of its own), Adams gets a scene alone with Hoffman, at the sink in their bathroom, when she shows him just who is the real “Master” here, in the most fundamental and brutal way a woman can, but the move smacks of desperation, not a certainty of her position.

But the movie as a whole is not, ultimately, about a relationship triangle, which is why the prison scene, in which Adams is absent, struck me so forcefully. What struck me, suddenly, was a reading of these two men as two sides of a disordered being, the same being.

Dodd’s mantra is that it is “not only possible, it is easy to eliminate all negative emotions.” We are not animals – we are spirit beings, inhabiting these mortal vessels for a short time. Quell, on the other hand, is a “poor animal,” as Dodd calls him, repeatedly. It’s not just that Quell doesn’t have any control over his emotions, or his sexual urges, or his very body; he shows no signs of having an interiority, a mind, at all. A soul he has, plainly; he feels a great deal, and deeply when he does. But he has no intentions, no real awareness of what he is doing even as he does it. From Dodd’s perspective, Quell is Caliban to his Prospero.

Quell’s “abberation” is obvious, to himself as well as to Dodd, but the nature of Dodd’s aberration only became clear to me in that prison scene. Dodd, precisely because he has lost touch with what Quell is so closely – too closely – connected to, his own embodiedness, has convinced himself that he is truly unconfined, the king of infinite space. And, as such, he cannot abide the existence of other minds, because they remind him of the confinement (what he asserts Quell is so afraid of) of his his own.

Dodd needs Quell, misses him when he is gone, cannot let go of him even though he is an obvious danger to “The Cause.” There’s a marvelous family dinner scene where wife, daughter and son-in-law all call for Quell to be banished, insinuating that he’s working for “some other agency,” accusing him of their own lusts, and pointing out, correctly, his penchant for violence, and asking whether, perhaps, he isn’t beyond help. But of course he’s beyond help. Dodd loves him because he is his missing piece, and because he is the only being, because he is mindless, who will never be a threat to him. And yet, if he cannot be Quell’s master, he will, he promises, be his mortal enemy in the next life, and show him no mercy.

The movie is set in 1950, at a moment of exceptional disconnect between mind and body in American culture, when mechanistic models of the mind became popular and “well-adjusted” was the way we described the mentally healthy. Anderson is saying something about that disconnect, about the madness and tyranny of the disembodied mind, and the loneliness of the body that cannot know itself. If I’m right that Quell and Dodd are, like Jekyll and Hyde, different sides of the same cultural personality, then the whole point of bringing Scientology into it isn’t to explain cults but to expose the cult-like nature of our own efforts at self-mastery, at least in our own crazy culture.

The movie ends, surprisingly, on a gentle note. This Prospero, unlike Shakespeare’s, does not drown his book, but publishes a sequel (bizarrely dug up in the Arizona desert). And this Caliban doesn’t curse his master for learning him his language, but puts that language to good use – the only use this or that Caliban really cares for: getting laid. The movie ends with Quell picking up a girl at a pub in England, and turning one of Dodd’s “processing” scripts – “you must answer these questions immediately, without blinking” – into a kind of teasing while they are having sex. Something has finally been mastered, but whether it is Dodd or Quell, or the language of self-mastery itself, I couldn’t say.

Comments