At Your Service: Wanderlust at the Stratford Festival

You’re A Good Man, Charlie Brown isn’t the only musical currently being mounted at Stratford to be based on the work of an enormously popular writer. Over at the Tom Patterson theatre, Morris Panych has directed his original musical, Wanderlust, based on the poetry of Robert Service.

Now, I wasn’t familiar with Service’s work prior to the show, and I’ll be honest, when I went into the theatre for the opening I had entirely forgotten what I had heard about the show beforehand. So I went in, as they say, cold.

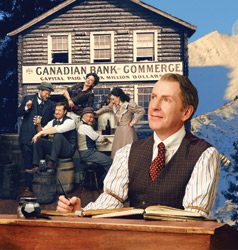

And my initial response was delight. Tom Rooney, who plays Service, a poet toiling away in obscurity in a turn-of-the-century British Columbia bank, plays him as a charming young smart-alec, quick with the quip and the comeback, and yearning to be more than he is. In short order, we learn that he’s in love with Louise Montgomery (Robin Hutton), the fiancee of his senior colleague, Dan McGrew (Dan Chameroy), and that he yearns for adventure in the frozen north of the Yukon, a yearning that his boss, Mr. McGee (Randy Hughson) tries to quash. Louise appears to love him back, and avers that she doesn’t love McGrew, but won’t commit to run away with Service, and he debates whether he will leave without her or stay and try to win her, all the while dreaming of his Yukon adventures and putting his dreams into verse – verses about a woman named Lou, and the shooting of Dan McGrew, and (most affectingly), the cremation of Sam McGee.

in obscurity in a turn-of-the-century British Columbia bank, plays him as a charming young smart-alec, quick with the quip and the comeback, and yearning to be more than he is. In short order, we learn that he’s in love with Louise Montgomery (Robin Hutton), the fiancee of his senior colleague, Dan McGrew (Dan Chameroy), and that he yearns for adventure in the frozen north of the Yukon, a yearning that his boss, Mr. McGee (Randy Hughson) tries to quash. Louise appears to love him back, and avers that she doesn’t love McGrew, but won’t commit to run away with Service, and he debates whether he will leave without her or stay and try to win her, all the while dreaming of his Yukon adventures and putting his dreams into verse – verses about a woman named Lou, and the shooting of Dan McGrew, and (most affectingly), the cremation of Sam McGee.

It’s a perfectly good setup. But halfway through the first act, I noticed: we were still in the setup. Nothing was happening. Service dreamed. Lou refused to commit herself. McGee urged him to stop dreaming and focus on his work. Dan McGrew alternated between mocking and threatening. And then, when we’d gone through that cycle, it would repeat. What, I wondered, was this play about?

So I turned to the program at intermission and discovered that Robert Service was this immensely popular Canadian poet, the only poet in history, I think, to ever have gotten wealthy off his verse, whose work has been memorized by decades of Canadian schoolchildren, and whose tales of adventure in the frozen north still thrill campfire sitters.

Okay, I thought: so this is going to be a story about how Service became Service. The irony is that this man who wanted to be an artist wound up being enormously popular, writing the sort of poetry that the bankers who mocked him would wind up preferring to the kind of writing preferred by the mandarins of academia; that this man who dreamed of being an adventurer wound up selling his imaginary adventures, peopled with magnified versions of the ordinary folk of his humdrum life, to a nation that presumably shared his longing for a fading pioneer spirit. That could be the basis of a pretty cool show.

But that’s not the show Panych wrote. Instead, Panych tries to make this the story of a love triangle – Service-Lou-McGrew. The plot, such as it is, builds to Service’s declaration of love, and his willingness to embezzle funds from the bank to provide himself and Lou with the means to run away in style, at which point he realizes that she was just scamming him for the money, and he reveals that, in fact, he didn’t steal the money in the first place, because . . . well, because he’s not the kind of guy to steal a lot of money.

This is a problem. First of all, there’s no more irony. We don’t know whether he succeeds as a poet, so we don’t know whether there’s any significance at all to his dreams – and those dreams are, really, all the play’s about, and are the only reason anybody knows who the real Service was. Second, Lou has no character, so who cares whether he gets her or not? Hutton left me cold for most of the show, coming to life only in her “it’s my turn” solo, but that song comes from nowhere and has nothing to do with the character we’ve seen to that point – it felt, in fact, like a song patched in precisely to provide her with a character, but you can’t do that with a single song. And the entire embezzlement plot comes out of nowhere, has nothing to do with what Service (the character, not the real man) actually cares about – and he doesn’t actually steal the money! Nothing, in fact, happens in this play, apart from Service learning that Lou cares more about money than she does about love, which is something he knew at the beginning of the play (when she says she’s going to marry Dan even though she doesn’t love him). So what have we been watching all this time, and why?

Other critics have complained that the music is at best serviceable, and that the choreography seemed cramped in the Paterson’s stage. I didn’t find either to be a problem. Service’s poetry has a sing-song quality that calls for merely tuneful music – you feel it was meant to be recited around a campfire, and a complicated melody would only get in the way. And I thought many of the numbers were engagingly staged. And the cast as a whole does an excellent job. Dan Chameroy knows how to play a swaggering bully; Randy Hughson how to play a crusty and cynical bank boss; Ken James Stewart how to play an insufferable corporate climber. Hutton, as I said, is rather opaque as Lou, but this may not be her fault – the character itself is opaque. Similarly, I found Lucy Peacock’s landlady-cum-madame to be absurdly over-the-top, but again, that’s not necessarily her fault, because all there is to the character is that absurdity.

The problem is not the direction. The problem is the story. The romantic triangle plot feels patched on as a substitute for the missing story, because it doesn’t spring from the central well that should animate this piece, namely: the relationship between writing and living. Service made a fortune writing about adventures he’d never had in awesome places he’d never been, selling his dreams to a people who bought them to experience a vicarious authenticity. That’s an interesting irony. If Lou fell in love with the writing without connecting with the man, then your love triangle would connect to that central theme, and Service would become Walter Mitty crossed with Cyrano. Now you’ve got a story, and once you’ve got that, what now feels like business – much of it good business, but still just business – turns magically into drama.

And if you want to discuss further, Morris, I’m at your service.

Comments