Non-Zionists With a Tailwind

We seem to be witnessing the remarkable early stirrings of a reevaluation of Zionism among American Jewish intellectuals. This process is parallel and perhaps symbiotic to the rethinking of America’s foreign policy relationship with Israel sparked by the best-selling The Israel Lobby and American Foreign Policy. But Steve Walt and John Mearsheimer, as fairly standard two state solution advocates, don’t differ very much in their prescriptions from views typically expressed by State Department or most postwar American presidents. Now however, there’s a new phenomenon. The past months have seen publication of Max Blumenthal’s excoriating journalistic portrait of the advance of a quasi-fascist Israeli Right in Goliath; the New York Times‘ spotlighting of a small but important group of religious and orthodox Jews who are non-Zionist or nearly so; and now John Judis’s remarkable analysis of the forces converging on Harry Truman at the time of Israel’s birth in Genesis: Truman, American Jews, and Origins of the Arab/Israeli Conflict. These are all the work of American Jews questionning whether Israel should exist as “Jewish state” with all that entails for the systemic violation of Palestinian rights. The very intensity with which the enforcers of mainstream “pro-Israel” orthodoxy have responded to this wave is itself a sign that the new voices have something of a tailwind behind them and are likely to be an increasingly important part of both the American Jewish and the broader American debate.

I would assume that much of the attention devoted to Judis’s work will be directed towards his portrait of President Truman and his ambiguity about supporting the particular Jewish state to which he served as midwife, as well to the unrelenting and crude political pressures the President was subjected to by the Zionist lobby. As Judis notes, Truman was a practical politician with ample experience in race relations and ethnically divided political communities. He favored without question the opening up of Palestine as a refuge for the tens of thousands of Jews languishing in displaced person’s camps after World War II. But he was not initially in favor of a Jewish state, in part because his top foreign policy advisors worried about antagonizing the oil rich Arab world and also because of his own sense of the American experience. Truman was, Judis relates, “a Jeffersonian Democrat who rejected the idea of a state religion—state religions were what had caused centuries of war in Europe. He didn’t think that a nation should be defined by a particular people or race or religion.” But he was also, as Judis makes very clear, a politician committed to his own reelection and that of his fellow Democrats. Reminders from the Zionists on his own staff and those outside the White House of the political dangers which would flow from refusing to accommodate Israel’s ever-expanding list of “asks” arrived relentlessly, and in the end Truman always bowed to them, protesting all the way.

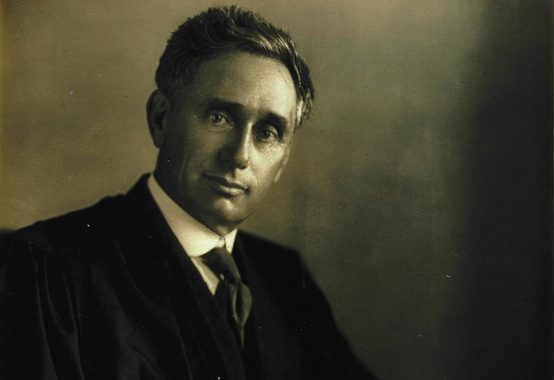

But just as important is Judis’s account of how support for Zionism advanced in the American political and intellectual class in the years prior to the Balfour Declaration and after. The critical figure was Louis Brandeis, the outstanding jurist appointed by Woodrow Wilson to the Supreme Court. Brandeis did not become a Zionist until he was 58 years old, influenced by, among other things, his involvement with a labor dispute involving Russian Jews far outside his rarefied social circles, and by recognition that the Protestant brahmins he encountered regularly no longer embodied much of the Pilgrim spirit he identified with America. American Zionists need not settle in Palestine themselves, Brandeis argued, but their support for the Zionist project made them better Americans. Missing from this ingenious argument was the slightest effort to grapple with what it meant to establish a Jewish homeland in a spot where another people already lived. Palestine for Brandeis was an empty room; the Palestinian Arabs were not even acknowledged in the Brandeis discourse. And he lobbied for a big Jewish state, far larger than even the World War I colonialist maneuverings of Great Britain had tried to engineer.

When in the 1920’s Palestinian Arabs began to object and eventually riot against Jewish settlement, Brandeis downplayed the objections, chalking them up to the agitations of absentee landowners. By the 1930’s, as Arab opposition to the Zionist project intensified, Brandeis, the “people’s lawyer” and esteemed champion of the poor and dispossessed, began to advocate the forcible “transfer” of the Palestinian Arabs to Jordan. He even brought bogus population statistics to Franklin D. Roosevelt, attempting to prove that Palestinian Arabs were not indigenous but instead were recent immigrants. This posture, as Judis points out, mirrored that of the most uncompromising Palestinian leaders—including the mufti who in the 1930’s proposed that all Jews who immigrated to Palestine after World War I be forcibly deported. Brandeis’s complete lack of respect for the rights of the people who dwelled in the spot where he wanted to create a Jewish state was commonplace among the progressive Zionists of his circle, including such major figures as Horace Kallen, Felix Frankfurter, and Stephen Wise. All these men were familiar with the tropes which had justified American settlement of the West and the various racist or hierarchical view of humanity, and were not adverse to using them. That the Arabs were savages, Indians,—this was used to justify Zionism. By World War II, as Americans had grown less triumphalist about their own Indian removal, Zionist groups began to excise such comparisons from printed collections of Brandeis’s speeches.

Another luminary who advocated ethnic cleansing was Reinhold Niebuhr, the Protestant establishment’s favorite theologian of the Cold War years. Niebuhr testified in favor of admitting Jewish refugees to Palestine, a standard liberal and humanitarian position. But he also endorsed the right wing Zionist scheme of population transfer, going on about the Arab “vast hinterland” in the Middle East, and endorsing “a large scheme of resettlement.” This idea were well outside of the mainstream of Anglo-American efforts to deal with a genuinely difficult problem, but Niebuhr’s “realism” took him to positions which in any other context would have been judged as simply immoral.

These revelations on the Brandeis circle and Niebuhr are among the most important of Judis’s book, for the light they shed on figures with luminous reputations as good progressives tells us much about ourselves. Such men, who have gone down in history as strivers for social justice, have never received the kind of critical scrutiny historians have devoted to, for example, procommunist intellectuals, who also advocated, or at least justified, breaking eggs to make different kinds of omelettes. Today we do not shy from the fact that Washington and Jefferson, despite being critics of slavery, were slaveholders themselves, and this knowledge both complicates and enriches our understanding of the American founding. So we owe thanks to John Judis for recalling to that personages routinely held up as epitomes of American hardheaded but humanitarian liberalism were proponents of ethnic cleansing. This is a significant part of the story of the 20th century, with consequences deeply resonant for our own time.

Comments