Yelling at Dead Authors

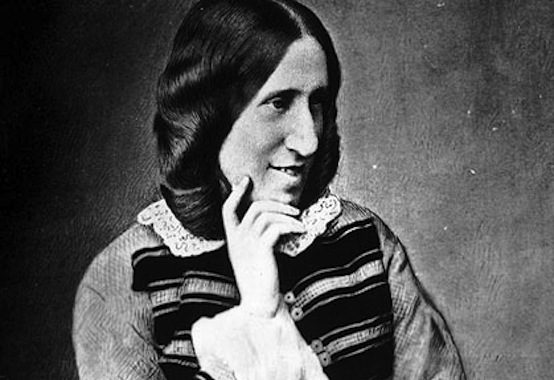

I am angry at George Eliot today. I just finished reading The Mill On the Floss, which, as per usual with me, took me far too long to finish in spite of my being thoroughly caught up in the story. When I finish reading Rod’s wonderful book (which is going much more swiftly) I may have some thoughts on the small-town panopticon inspired by both books, but right now I am too busy being angry.

I’m angry at the ending. (If you don’t like to have a 150-year-old novel “spoiled,” you should stop reading now.) Eliot, having taken us with her heroine, Maggie, on a tempestuous journey guided by (mostly noble, if mis-guided) passions, has finally brought her home to port, and to the question of how, after such a journey, and the knowledge that comes with it, one is to live. The important relations of her life are largely resolved – peace is made with her cousin, Lucy, with her faithful of resentful lover, Philip, and with her seemingly most-unlikely aunt, Mrs. Glegg; no such peace appears possible with her fierce brother, Tom. And I looked to learn whether Maggie would, in fact, have to leave St. Ogg’s, or whether she would carve out a place for herself there in spite of the town’s disapprobation; whether she would “settle” for Philip after all, or resolve on a solitary life; whether she would carry a torch for the plainly undeserving Stephen, or whether, as she aged out of passionate intensity, she came to see what was so manifestly unattractive about him to this reader.

And then she up and throws a calamity at her characters in the form of a massive flood that drives Tom and Maggie, the estranged brother and sister, briefly together before killing them.

And I’m still fuming about it! It felt like she took people I believed in as people and had long since stopped reading as schematic figures – Tom all pride and judgment, Maggie all passion and sentiment – and roughly yoked them back into an allegorical relation that could not but kill them. Why would she do this to them? To me?

I found myself meditating on Mary Anne Evans’s own life (with which I fear I am insufficiently familiar to meditate adequately) to try to make sense of her decision, wondering where she might have been in her own journey. Evans’s life attests to an appreciation for setting one’s star by love – physical and spiritual – above either personal or societal interest, and Maggie Tulliver, who so fruitlessly struggles to orient herself by some other star, is a transparent author-surrogate. But it felt to me as though something wasn’t yet worked out – that would be worked out later, in Middlemarch – about this character; that, in 1860, there was still a reason she could only be redeemed through annihilation.

It’s a testament to the power of the writing that I could be invested enough to be angry at it. But I am curious whether others have had that experience with this novel. It felt, to me, like a very late failure of moral imagination on Eliot’s part – but, even if I hold to the notion that it’s a failure, that doesn’t mean I’ve got the cause right. The reason could as easily have been commercial – which would tell us something about the sensibilities of the Victorian reading public – or an instance of structural considerations predominating over questions of character (I realize that where I “wanted” the novel to go, in its last pages, would amount more to settling in or even petering out, which is usually less-satisfying than ending with a bang).

Any Eliot scholars among my readers care to help me out?

Comments