Williams, El Memorioso: The Glass Menagerie On Broadway

In his short story, “Funes El Memorioso,” Jorge Luis Borges describes a man who is incapable of forgetting anything. As a consequence, he is completely incapacitated, capable only of cataloguing in excruciating detail all the facts that he remembers, but unable to derive meaning from any of them. He can’t make sense of reality, because making sense of reality means emphasizing some facts, some events in the narrative thread, more than others. It involves, in other words, selective forgetting.

I thought about Borges’s character, crippled by perfect recall, last night at a performance of Tennessee Williams’s play, The Glass Menagerie, currently running at New York’s Booth theater.

The Glass Menagerie, Williams’s first masterpiece, is narrated by its protagonist, Tom (Zach Quinto), an obvious stand-in for Williams himself. Tom lives at home with his mother, Amanda (Cherry Jones) and his sister, Laura (Emily Keenan-Bolger). His mother is a faded Southern belle who married ill-advisedly and, abandoned by her husband, has fallen on very hard times. His daughter, Laura, well – Laura is special, and whether she is special in the sense of being extraordinarily valuable, or merely special in its modern condescending meaning is one of the deeper mysteries of the play.

The time is the depths of the Depression, and Tom is the primary breadwinner for the family, working long and tedious hours at a shoe warehouse, increasingly desperate to escape, see the world, have experiences that would be the basis for the poetry that he desperately needs to write, before his very life bleeds out. But he can’t leave, says his mother, until some provision has been made for his sister, who cannot stomach a job (I mean that literally), and doesn’t seem very likely ever to marry, given her painful shyness, her gimpy leg, and her preference for tiny glass animals over human contact.

Described like that, it sounds like a quaint period piece. But Williams – and, indeed, Tom himself, in the prologue to the play – make it clear that this is not a kitchen sink drama, but a play about memory itself. And this production, directed by John Tiffany, which began its life at Boston’s American Repertory Theater last year, takes that authorial mandate very seriously. Over and over again, the production makes it very clear that this is not a “realistic” drama, but something far more expressionist. The efforts begin before the curtain (which is nonexistent), with an exceptionally striking set (designed by Bob Crowley).

That set is dominated by the steps and platforms of a fire escape that tilts upward at a rakish angle towards infinity, like a parodic version of Jacob’s ladder on which the angels ascended and descended. Or, alternatively, like a mast, the ladder leading to the crow’s nest – a match for the similarly slanted bottom floor of the fire escape, whose pointed railing distinctly recalls the prow of a ship. These are, perhaps, allusions to Tom’s ambition to join the merchant marine and sail out of a life and a family that had become a trap; if not, then certainly a powerful way to communicate the sense of this little community’s isolation, the distance one would have to travel to get from here to the “real” world.

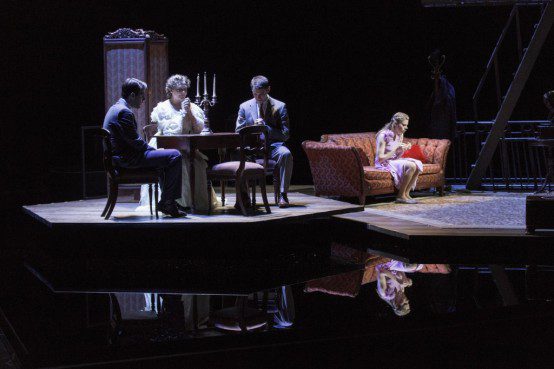

But this is not the only nor even the most distinctive scenic element that expresses that distance. The action takes place on a group of platforms that hover above an inky black pool. I mean that literally: black liquid covers the bulk of the stage. During the action, little points of light periodically wink into existence within the black, and one character or another (most frequently Laura) gazes out into what may be cold stars, or only shards of shining glass.

As I say, this may also be a metaphor for the distance – in space and time – that Tom has traveled, and put between him and the home he loved and hated. But I read another meaning into it. More unequivocally and emphatically than in the other productions of Glass Menagerie that I have seen, this is Tom’s play. This is his memory we are seeing. And the blackness that surrounds this home read to me not primarily as distance traveled, but as what his mind has selectively forgotten. This scene, of the home he abandoned, is what he remembers. The other scenes of his life take place in blackness – they are what he has forgotten, which is what gives this scene prominence. Which is what gives his life meaning.

The first character to join him on-stage, his sister, Laura, enters in such a way as to remove any ambiguity about whether we are to understand her as “really” there. She emerges – is pulled out by Tom, actually – from inside the living room sofa. Even if you know it’s coming, it’s a very startling image. His mother, Amanda, enters in a more common manner, but not in a common style – she is summoned by him, and stands in readiness to play her scene, rather than entering as a personality already in motion. This play, then, is the play Tom has written in his mind, made of the elements of his past that he cannot forget, and that we are privileged to see staged because we have intruded on that mind – or, better, because Tom has finally become a writer, and has chosen to invite us in.

The production indulges in some expressionism in the acting as well – characters staring off into the blackness, losing their place in the moment; characters pointing in odd directions and following their fingers; eating or clearing the table with sweeping gestures unrelated to food or cutlery, and without props to anchor their actions – that didn’t do much for me. But the larger conceit in which those motions (choreographed by movement director Steven Hoggett) are embedded – that this is not how it was; this is how Tom has constructed it in his memory, what he has made important by recalling it – is a powerful interpretive lens indeed.

And how does Tom remember it? Well, he has certainly put his mother in her place in his memory. Cherry Jones’s Amanda is probably the funniest I’ve ever seen, and is consequently a powerful presence, but the humor is substantially at her expense. I thought about some of the women in John Guare or Christopher Durang who were born in Williams’s shadow, and felt that this Amanda shared more than a passing kinship with them. (I also – and I know this is shallow of me – could not get away from the fact that Cherry Jones, in shapeless baggy ’30s dresses and hair in short curls, looked alarmingly like Jonathan Winters in drag.) Tom rolls his eyes at her extravagant absurdities, and we roll our eyes with him. It’s not until near the end of the first act, when Tom reveals that he actually has invited a gentleman caller to dinner (as his mother begged him to do), that we see how deep the well of genuine affection is between mother and son – and I breathed a deep sigh of relief.

And Laura? Well, Laura doesn’t have very much to do in Act I of the play – she is, after all, pathologically shy. But Amanda tells us that “still waters run deep” – that she notices things others might not. I didn’t quite see that, I admit (and the line is played purely as a laugh line by Jones, because one of the things she notices is that Tom is unhappy, which is so obvious, someone shallow as a puddle would have noticed). But more to the point, I didn’t see what Tom saw when he saw Laura. The choice not to have an actual menagerie of glass figurines on stage means there’s no opportunity to watch Laura lavishing attention on them, or to watch Tom watching her. We see her, but we don’t see her as Tom sees her.

Keenan-Bolger doesn’t come into her own until Tom leaves the stage, and she’s left alone, after dinner in Act II, with her Gentleman Caller (Brian J. Smith), one James O’Connor. Her one date turns out to be the only man she ever had any interest in, her high school crush whom she hasn’t seen for years, and who vaguely remembers her but can’t place her. James was the hero of the school, a scholar, athlete, singer and debater, universally acclaimed as most-likely to succeed. And he’s also, the prologue tells us, the most “real” person in the play – somebody, in other words, that Tom hasn’t had to shape and mold in memory in order to derive meaning from him. Well, life hasn’t turned out like James thought, whether because of the Depression or because, well, life doesn’t turn out like you think, and he’s stuck in a job almost as crushingly depressing as Tom’s.

But Laura still sees him as the high-school hero, and, realizing this, he warms to her, and to the opportunity to be that hero again. Before he knows it, he’s incipiently falling in love, and has to stop himself before he goes to far. Because he’s already engaged to another girl – a more normal and appropriate girl, but for that very reason less special than Laura is.

The whole scene between the two of them is beautifully executed. I believed fully in James’s sincerity (Smith does a fine rendition of Midwestern can-do optimism barely covering a deep fear of failure), and Keenan-Bolger’s Laura blossomed ever so gently, almost without us noticing – and then there she is, speaking almost confidently about her lack of confidence. There’s no “oh, brave new world” moment where she realizes she might actually have the man of her dreams – she’s still herself, behaving completely naturally, and he’s responding, and she’s responding to that response, and something is growing. And then it dies, and we see her die in response, but oh, so quietly. It redeems much of what felt to me too invisible in the first act.

But here’s the thing about the play itself: Tom didn’t see that scene. He wasn’t there to see it – it happened while he was out of the room. It can’t, be definition, be his memory. What does it mean, then, that we see it, and that so much of our understanding of Laura, who she is down there in the depths, comes from it?

I mentioned earlier that one of the mysteries of the play is just how “special” Laura is. How pathological is her shyness? Is it something that, today, we would medicate? I suspect – for better or worse – that it is, and that if a play were written about a character like Laura today, her narrative of recovery – and she would have a narrative of recovery – would be a medicalized one. That’s an anachronistic perspective to impose on the play, but it’s a question that a production has to answer up front. Is Laura just really shy because of her limp? If so, then isn’t James O’Connor right that she just needs a bit more self-confidence? But he isn’t right, is he – there’s something deeper that keeps her apart from people, something not so easily overcome. What is it? How do we show it onstage without reducing Laura to a condition?

I’ve seen Laura played as someone on the autism spectrum, and it’s a problematic choice for a variety of reasons. I’m glad Keenan-Bolger didn’t go that route, even though I was frustrated by what I perceived as an opacity in her Act I scenes. But this scene, between Laura and her Gentleman Caller, is the answer, I think, to my question of how to show who Laura is inside without contradicting what we know about who she is outside. This scene must be Tom’s creation, what he has interpolated between when he left the room and when he returned, to learn that his friend has left early, and that all their efforts were in vain. Because he created it, he can take us inside the still waters and show us their depths, show us what he sees that we have not, can even make James see it, unlikely as that may seem.

The scene is a beautiful gift to Laura, but a thoroughly inadequate one next to the gift of his actual presence in her life. But Tom can’t rewrite history; he can only fill in the gaps. James does leave, never to return. Amanda blames Tom for the fiasco, and that blame is what precipitates his flight from the family, from what, belatedly, in the present of the play in which Tom is the narrator, he has learned he cannot escape. All the “experiences” he accumulates won’t matter next to the experience of growing up with his sister, Laura, loving her, fearing for her, fearing for his own inability to do anything for her. And then abandoning her. That’s all he really has to write about. It’s all he really remembers.

The sorrow and pain of that knowledge comes through sharply in Quinto’s last monologue before the candles go out. And that’s the play.

The Glass Menagerie runs through February 23rd at the Booth Theater in New York.

Comments