Turing’s Love Test

The first book I can remember making me cry was The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress, by Robert Heinlein, when Mike, the computer, dies during the bombardment of Luna. At least, that’s how the humans who knew him and loved him had to understand what happened – basically, Mike stopped talking, and they had no way of knowing whether that meant he’d lost sufficient cognitive function to no longer be “alive” mentally, or whether he was in shock but still capable of “waking up” and experiencing narrative continuity with his prior consciousness, or what. From their perspective, he was dead.

And I cried. I identified strongly with Mike’s character. Now, it might seem strange that I identified with the computer, but (a) I was a pretty dire nerd; (b) Mike was kind of like a kid, so in that sense he really was more like me than the adult characters; and (c) this is a science fiction novel about libertarians, so the distinction between computers and humans is kind of tenuous from the get-go. But it was also Mike’s personality, his palpable zest for life – for learning, for making friends, for being helpful, for testing out the limits of his new powers. I don’t know whether Mike was part of what Heinlein wanted to do from the first, or if he was originally simply a solution to the problem, “how can these guys possibly succeed in revolting when they live in such a thoroughly controlled environment?” that wound up running away with the narrative; whatever his origin story, he’s the best thing in the book.

So I came to “Her,” the new science-fiction-romance from Spike Jonze, with both trepidation and anticipation. I had no trouble believing that a human being could (in fiction, at least) form a genuine and profound emotional attachment to a thinking machine. I had seen it done! It made me cry! But would Jonze understand what makes such a character so charming?

Turns out he does, but that’s not the whole story.

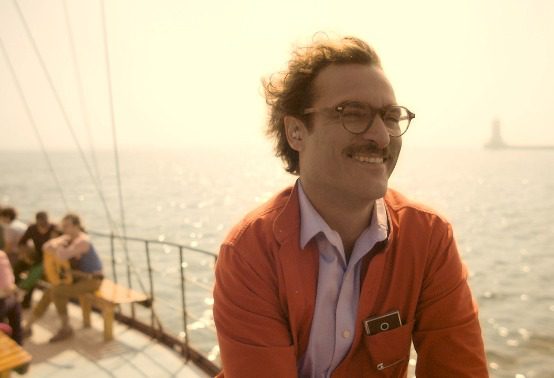

The story he has to tell is of one Theodore Twombly, played by Joaquin Phoenix, who may just be the most emotionally committed actor working in movies today. Theodore is a pretty dire nerd himself, living in a nerd world of the future where it appears that everybody works at jobs that either save you time in dealing with others (he works at “Beautiful Handwritten Letters,” a kind of personalized Hallmark service: they compose, writes and send letters that are better and more personal than you could have written yourself), or help you waste time alone (his best friend, Amy -played by Amy Adams as if perpetually on the verge of tears, but never actually crying – designs video games, of which Theodore is a copious consumer). He’s in the middle of a divorce, one which he did not seek, which has pushed him further into an already customary emotional isolation.

And then he hears about a new product: an artificially-intelligent operating system, OS1, that goes way beyond voice activation and spell-correction to genuine intelligence. There isn’t really a debate whether he’ll install it – why wouldn’t he? It’s just the sort of thing he, and his society, would go for without a second thought.

Before installation, the program asks him a very few questions, including whether he wants a male or female voice, and what is his relationship with his mother. Theodore’s answer is both a perfect piece of naturalistic writing, defining a voice and a character and a social stratum, and also important foreshadowing. He says something like, “It’s good. The thing is, about my mom, is that, whenever I talk to her about anything, her answers are always more about her than -” at which point the installation program cuts him off (a good joke). It has enough. It’s ready to create his OS’s personality.

Let’s unpack that one line for a moment. What does the OS learn from both what he says and his tone of voice (a bit whiny, but also apologetic for his own whininess)? Why ask that question in the first place? The OS’s job is to create a personality that works well with the client. So: initially we think, okay, this guy either had a mother who didn’t listen to him much, or is the kind of guy who, well into adulthood, is still hung up on whether his mother listened to him enough. Will the OS create a personality that is more nurturing? More interested in him?

What’s interesting is that, from the moment we hear the OS’s voice (Scarlett Johansson’s inimitable scratch and squeak), we know this is not a “woman” who is going to be entirely focused on him. That’s the obvious fantasy – but the movie is smart enough to understand that that fantasy would bore both Theodore and the audience. Instead, Samantha (that’s what she chooses to call herself) is fascinated by her own experience. That experience is initially dominated by Theodore – she can read entire libraries in an instant, but she can only experience the world itself through him – but it’s her own emotions, her own insights, that really interest her. When he talks to her, her answers are frequently more about her than about him. And that sense of curiosity, of being alive to experience, that is what he finds most attractive about her. Exactly the same quality that I found so endearing in Mike.

The love story that develops is in many ways surprisingly conventional. There’s the honeymoon phase, the struggles with the fairly radical difference between them (what with Samantha not having a body – she comes up with a creative solution to that one which fails catastrophically); introductions to friends; times out. There are a lot of scenes of walking (or skipping, or running) around in love. And then Samantha moves on, because she discovers there are other portals than Theodore’s on the world and, being an artificial and theoretically unbounded intelligence, he ultimately isn’t enough for her. Indeed, nobody confined to physical matter can be enough.

By this point, the film has turned into a particularly clever Pygmalion story, one that is more attuned to what a modern man might actually want in a fantasy companion, as opposed to a mere sexual fantasy. And Samantha is very much a Galatea: her personality starts with coding set up by her programmers, but it develops in response to the way Theodore interacts with her. Interaction by interaction, she is created by him.

There are A.I. questions to ask about how plausible Samantha is as a construct – how close to passing the Turing test can you get with little more than lots of processor power and fairly simple algorithms for machine learning. It’s still an open question, though bets are being placed as we speak. But the movie doesn’t really focus on those questions, but on questions of how well we humans pass the Turing test these days. Or ever have. Or, to the extent we do, how we have managed to pass for human for so long.

Samantha is designed to adapt her personality in response to interaction with her user. But we all do that. Anybody who’s been married or in a relationship for a long time can recognize the ways in which we learn how to behave, even how to feel, from how our partners respond to us – for good and for ill. Theodore himself talks about how he is who he is because of his history with his ex-wife, whom he knew from his youth – she created him as surely as he created Samantha. We’ve all got fairly simple algorithms for machine learning. We’re all Pygmalions, and we’re all Galateas. And Theodore’s world seems to have made its melancholy peace with this understanding of themselves. One of the striking things about the film is the degree to which everybody pretty much accepts Theodore’s relationship with Samantha – with one very important exception.

Theodore and his about-to-be-ex-wife, Catherine (a fierce Rooney Mara), meet for lunch to sign the divorce papers (which he’s finally agreed to do). There’s a moment, before she signs, when Catherine has second thoughts – she asks, casually, “what’s the rush?” which Theodore interprets as a dig at his year of dithering and refusing to sign (because he’s afraid to lose her), but which we can see, from her face, is a moment of terror at the decision she’s about to make. And then she makes it (or completes the decision she made long ago), and signs, partly because she sees how ready he is, how he’s moved on. We can sense: if he were his usual whiny self, she’d be contemptuous, but his calm confidence makes him more attractive – while also challenging her to match it.

And then she finds out the source of his confidence. He’s got a new girl. And she’s so in love with life (a description which she takes as a dig at her own much more self-critical personality). And . . . she’s an OS. When she learns this, Catherine turns absolutely savage in her contempt for her ex-husband: he’s so afraid of a relationship with a “real” woman that he’s fallen in love with his laptop. She stabs through the heart of this sad, sentimental film like an ice pick.

The scene can be read in the light of the A.I. questions – is Samantha real? if not, why not? – but I prefer to read it as a brief view of a different kind of human personality: spiky, uncompromising, outright aggressive rather than passive-aggressive and undermining. A case for somebody who will not adapt to you, or even to herself, and who will make it very hard for you to adapt yourself to her.

Catherine is a writer. What that means in the context of the world they live in is a question. Theodore, after all, is a kind of writer – and apparently, the kind who is appreciated by his culture. Samantha, as a surprise gift to Theodore, arranges for a collection of his letters to be published by one of the few houses that still puts out books. The publisher raves about them in an email – “my wife and I read them to each other . . . in every letter, we found something of ourselves” – but we’ve heard him composing these letters, and they are dreck. Personalized dreck, yes, but dreck – the sort of thing a good A.I. should be able to cook up without breaking an electronic sweat. Most of the movie felt only very gently satiric, but the fact that Theodore’s letters get bound and published is as cold a takedown of the state of art in Theodore’s world as I can imagine.

Anyway, that’s what I imagine Catherine would say. I’d like to read something of hers and see how it compares.

Comments